Just eight years after Colonel Muammar Gaddafi was killed, Libya remains in a state of murderous chaos. Kim Sengupta, defence and security editor for the Independent, witnessed the end of the Gaddafi regime. In an extraordinary analysis he looks at Gaddafi’s surviving family, Libya’s oil struggles, and – most explosively – shows how directly the dictator’s death contributed to Europe’s migrant crisis.

Endgame

The bodies of Muammar Gaddafi and his son Mutassim lay in a meat warehouse in Misrata. The eyes were shut in seeming repose, but the shrouds of white cloth thrown over them did not hide the wounds inflicted. A queue of people, young and old, men and women, families with babies, shuffled along the room, staring down at the corpses, whispering among themselves. This was the fate of the man who had ruled Libya for 42 years at the end of what was, at the time, the most violent revolution of the Arab Spring. He and his son – who was also his National Security Adviser – had been captured, tortured and killed as they tried to escape from their last place of hiding, the hometown of Sirte.

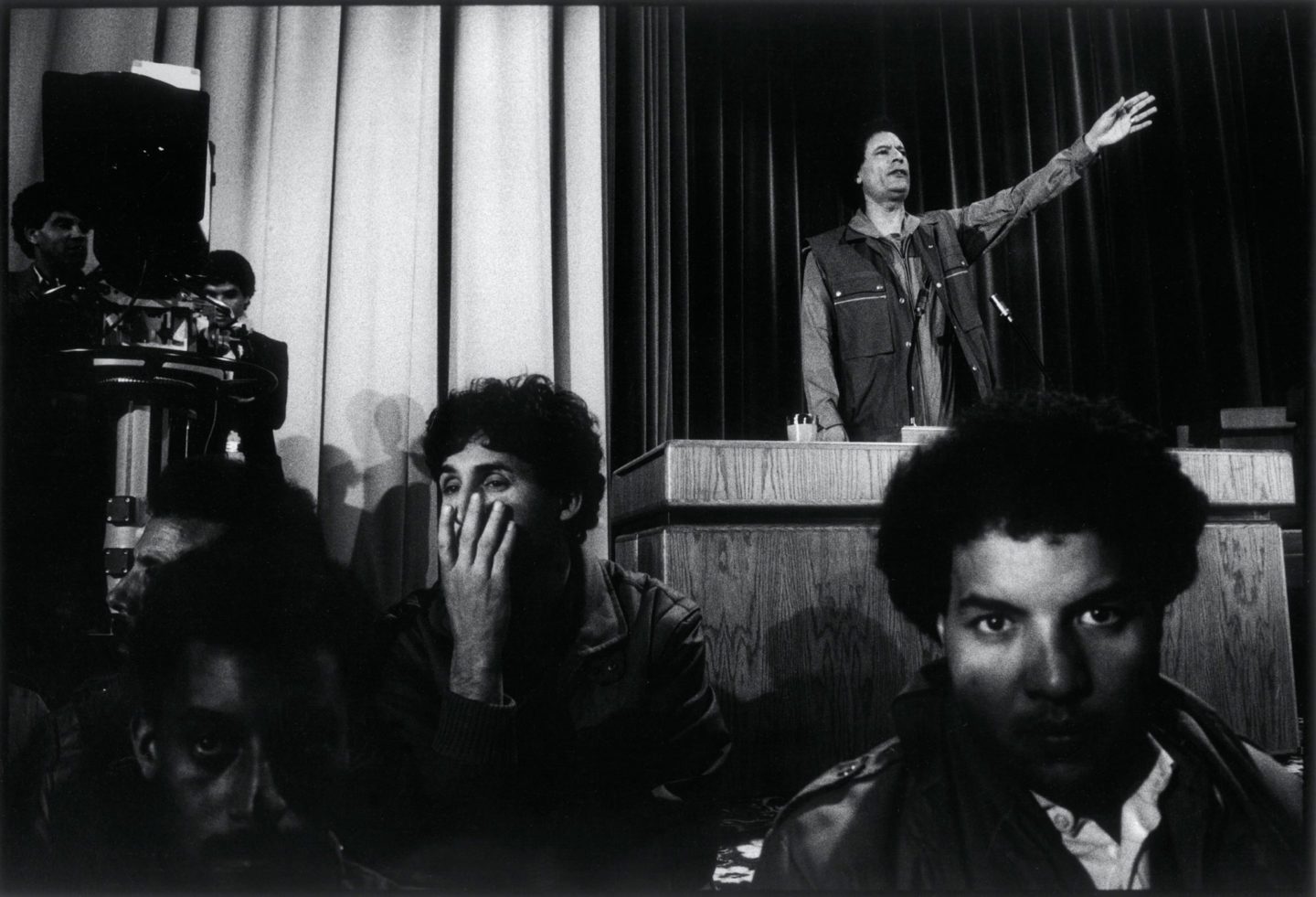

Colonel Gaddafi, President of Libya, holding court at an indoor rally in Tripoli while security stands guard in front of him. Photography: Peter Jordan.

There was morbid fascination, a sense of celebration, but also unease among those present. I talked to Firuz al-Maghri, a 55-year-old schoolteacher, who shook his head as he recalled a brother and a cousin who had died in Tripoli’s Abu Salim prison, a place of fear and despair. ‘Twelve hundred prisoners were murdered there,’ he said. ‘It is difficult for outsiders to understand, but Gaddafi was responsible for so many lives lost, families who never found out what happened to those who disappeared. We feared him, I was afraid. But seeing him like this…’

Rahim Abu-Bakr who had left his job as an engineer to become a fighter patted his shoulder. ‘It does not matter. He cannot hurt people any longer. What happened at the end to him and his son was bound to happen, but this was a bad death… We need to leave all this behind and move forward.”

A fractured future

A new government was announced in Benghazi a few days later by the National Transitional Council. The new leaders proclaimed a great future for the country emerging from the shadow of the tyrant. There were calls for religious freedom and unity and equality. But there were also demands for Islamic piety and the promulgation of strict Sharia laws. Following Gaddafi’s strident anti-Islamism, it was an early indication of differing visions for the future.

At the time such differences were swept away with declarations that Libyans would sort out a future system best suited for them. From the most optimistic perspective they had considerable oil wealth to help them make the transition. But the revolutionaries were divided into different factions from the outset. Not only was there the likelihood of strife in the future but concerns about how to handle outside influence – be it from the US and Europe or from regional powers – meant that the Libyans would struggle to shape their country on their own terms.

‘Now listen, you people of NATO. You’re bombing a wall which stood in the way of al-Qaeda terrorists. This wall was Libya.’

Muammar Gaddafi

When the revolution had started there had been posters proclaiming, ‘No foreign intervention, Libyans can do it alone’. It became clear soon that they could not, since outside intervention had proved key to the regime’s defeat and the rebels’ victory.

I was in Benghazi on a drizzly Saturday when Gaddafi’s tanks rolled into the city, past shattered homes and charred cars. The palpable fear was of retribution against those who had dared to rise up. Some had managed to escape, but many were trapped, expecting the worst. As Mashala, my translator and friend, who had several activist brothers, starkly put it, ‘he will kill us all’.

The regime’s forces could have taken the city that day, albeit with a lot of bloodshed. The resistance was brave but in retreat. Yet the army commanders chose to pull back and relaunch the assault the following day with reinforcements.

It proved to be a fatal mistake. The air strikes, by the French and British, began that night. We saw the terrible result the next morning – a scene of desolation on a field edged with wildflowers whose prettiness jarred with the bloodshed. Gaddafi’s forces had been caught without cover; before us was a ghastly miniature of the carnage that had been wreaked on the road to Basra in 1991 when American and British warplanes had bombed Saddam Hussein’s forces as they retreated from Kuwait. All around us was an open-air charnel house of twisted smoking metal and charred bodies of men incinerated with no chance of escape.

The course of the war had changed. The ambiguous terms of UN Resolution 1973, which allowed the establishment of a ‘no-fly zone’ was translated by NATO into a fully-fledged air campaign allowing the First World’s most advanced military machine to systematically destroy one from the Third World. Even then it took months of bombing for the regime to fall. In that time, dozens of rebel groups sprung up, some of them supported with guns and money by wealthy sponsoring states in the Middle East, some with extremist Islamist links, all determined to fight for their division of the spoils.

Outsider fickleness would prove every bit as harmful as outsider meddling. The country’s problems were compounded by the fact that the West effectively withdrew from Libya after the fall of the regime, leaving the UN without a proper stabilisation force. The US’s withdrawal was hastened by the murder of Ambassador Chris Stevens and three other Americans in Benghazi by Islamists, believed to be Ansar al-Sharia, which was linked to al-Qaeda in Maghreb. Recriminations followed, not least about whether Hillary Clinton as US Secretary of State should have foreseen the danger. After an attempted ambush soon afterwards of the British ambassador, foreign diplomatic presence dwindled.

The bloodied body of Colonel Muammar Gaddafi in Misrata.

Blood legacy

As Libya lurched into a vicious circle of chaos and violence, one of the key questions was what would happen to the family of the man who had held the country in an unrelenting grip for 42 years? Gaddafi had fathered nine sons. Beyond the gory theatre of death that marked the end of his own life and Mutassim’s on October 20, 2011, what did the shattered future hold for those who remained?

Khamis, Gaddafi’s seventh son – who had a brigade named after him – was already dead. Following several false reports of his demise, he had eventually been killed in a NATO war strike on 29 August. Saadi – his third son, who had been a footballer as well as commanding Libya’s Special Forces – fled to Niger, and from there was later extradited to Libya. Hannibal, his fifth son – a maritime consultant – found refuge in Oman. He went on to be arrested after travelling to Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley and is currently imprisoned in the country. The Colonel’s wife, Safiya, and daughter Ayesha, who was once part of Saddam Hussein’s legal team when the Iraqi dictator stood trial in Baghdad, went to Algeria where she gave birth to her fourth child. Her husband Ahmed al-Gaddafi al-Qahsi, an army colonel, had already been killed in Tripoli.

Yet in terms of Libya’s immediate future, the most significant of all Gaddafi’s remaining family was Saif al-Islam, second son of Gaddafi’s second wife and anointed heir apparent, who was caught as he tried to flee Libya. An LSE graduate who had been seen as a potential moderniser, once the fighting kicked off he had revealed the full force of his hostility to the West as it backed the rebels in their assault on his father. After the uprising, Saif was incarcerated in the southern city of Zintan by the Abu Bakr al-Siddiq Battalion who controlled this area. Notoriously during this time he lost two fingers and part of a thumb. Some say they were cut off by torturers because he used them to give V for victory salutes while vowing to crush the rebellion, others say the maiming of his hand is consistent with an explosion injury. Questions about his status during this time – whether he was really a prisoner, or in fact being protected by his captors – have never been fully answered: the one thing that is certain is that he was eventually released in 2017.

The imprisonment certainly saved Saif’s life, since he was sentenced to death in absentia by a court in Tripoli on July 28, 2015. Arguably he owes it his current liberty too, since he was indicted for war crimes by the International Criminal Court in the Hague in 2011. Now, as Libya’s brutal and chaotic civil war shows no sign of resolving itself, the extraordinary possibility is that Saif might become president. This is obviously in the context of an apocalyptic fallout where all political bets are off, yet the mere fact that he has repeatedly made such intentions public is something that would not have been deemed possible even five years ago.

‘Oil, unsurprisingly, remains a more powerful factor than any of Gaddafi’s sons.’

An unlikely pact

Saif first announced that he would run for the position on 22 March 2018, as a candidate for the Popular Front for the Liberation of Libya. This October, he was given an important boost when former army General Khalifa Haftar went on the record to declare that he had every right to put himself forward to run the country.

Even amid the quicksand uncertainty of Libyan politics, Haftar rises up as a colossus. Over the course of his lengthy career in the Libyan military, the 76-year-old has had links with both the CIA and Russia. Currently he is backed by a rival government – in Tobruk to the east of the country – which was set up in opposition to the UN-supported Government of National Accord. As military commander of the self-styled Libyan National Army he has presided over a series of victories in battles against Islamic extremists that has led many Libya watchers to see him as guarantor of crucial stability. Right now he is continuing a months’ long struggle to seize Tripoli from the Government of National Accord, which in turn condemns him as a war criminal.

In his latest power-grabbing incarnation, Haftar has been backed by the UAE, Egypt, Russia, and it is claimed, covertly by France. The UN-backed government is supported by Italy, the former colonial power in Libya which has been the most constant Western presence in Libya since the war, and Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s Turkey. The US officially supports the Government of National Accord. But – in yet another indication of the treacherous complexity of the situation ¬– Donald Trump gave the green light in a phone call in April for Haftar’s Libyan National Army to launch the assault on Tripoli.

Haftar’s breakthrough acknowledgement of Saif has, it would seem, more than a little to do with Russia’s involvement. The Kremlin’s growing intervention in Libya is part of its return to the Middle East and North Africa as a potent force. Haftar has travelled to Moscow three, possibly four, times in the last three years, meeting among others the Defence Minister and the Foreign Minister. Beyond this Moscow is printing Libyan dinars for Haftar. This is especially important because many of his ‘victories’ have been obtained through paying off tribal leaders, and also providing military supplies.

It’s become particularly clear that Saif has strong links with the security company Wagner Group, Moscow’s mercenary army, which is deployed in countries from Venezuela to the Central African Republic. This shady organisation is owned by Yevgeny Prigozhin, a balding 58-year-old dubbed ‘Putin’s chef’ because of his multiple lucrative government catering contracts. More than a hundred members of Wagner are said to have arrived at the frontline this September to help with Haftar’s stalled offensive against Tripoli. In an attack this October, 35 of them were reported to have been killed.

The Wagner Group initially pushed for Haftar to have ultimate control, but like anyone who dares venture into Libya these days, they are aware of the nostalgia for the old order. It’s a sentiment my colleagues and I have increasingly heard. While Haftar has been presented for a long time as the strongman to fill the void, Saif’s support base is growing. Within Libya itself there is nothing to stop him legally anymore. Significantly an edict passed in 2013 banning officials in Colonel Gaddafi’s administration from standing for public office was revoked two years later.

Gaddafi-era officials wait for their trial in a prison cage in Tripoli on 28 July 2015.

Documents leaked this September provided proof of the Wagner Group’s direct promotion of Saif al-Gaddafi. Last April it presented him with a power-point proposal for strategy. The company has restarted Jamahiriya TV, a channel which was used to disseminate his father’s view of the world, and had moved to Cairo from where it had been broadcasting intermittently. Wagner also set up a dozen Facebook groups promoting both Saif and Haftar.

Yet in a situation where splintered loyalties are the norm, it’s not entirely surprising that the leaked papers were also critical of Saif. He had, it was claimed, ‘a flawed conception of his own significance’ and needed to be diligently monitored for any project to work. ‘We can’t meet him once a week, we need a constant presence,’ officials concluded.

This means that yet another Gaddafi son has come into play. Moscow has been keeping its options open by approaching Lebanese officials to offer Hannibal sanctuary. Hannibal has now been in prison for four and half years. According to his friends he is suffering because of inadequate medical care for his deteriorating condition in jail.

Hannibal was abducted by a Shia militia in the Bekaa Valley after he crossed the border. He was quickly released but he was then almost immediately arrested by Lebanese security forces in connection, it was announced, with a decades’ old mystery surrounding the disappearance of a charismatic and influential Shia imam, Musa al-Sadr. The Lebanese-Iranian imam, a prominent broker for peace and interreligious dialogue, went missing after visiting in Libya in 1978. Many in Lebanon hoped Gaddafi’s fall would allow information to come to light about what happened, but it did not.

Hannibal’s lawyers stress that the Lebanese government has not offered any evidence showing his culpability in the Musa al-Sadr case. I was among the journalists who discovered voluminous amounts of confidential documents in government buildings in Tripoli in the aftermath of the Gaddafi’s regime’s fall – not least on the involvement of the British government in rendition. Yet we did not come across anything relating to Imam al-Sadr. A meeting brokered by Russia was held in Hannibal’s prison cell more than six months ago. But it remains unclear if any further development has taken place in the matter.

Children play on destroyed tanks in Misrata, some 200 km east of Tripoli, on 1 September 2019. Photography: Amru Salahuddien.

The oil factor

The fact is that when considering the most important aspect of Muammar Gaddafi’s legacy, the uncertainty surrounding his bloodline means that maybe it isn’t as significant as another liquid that’s thicker than water – oil. For this, unsurprisingly, remains a more powerful factor than any of his sons.

It was Muammar’s seizing of control of most of Libya’s oil-reserves that kicked off the 1970s Arab petro-boom. It is also the reason why today few Libyans believe that foreign intervention in their country is motivated by altruism. The country was once Africa’s third largest producer with an output of 1.6 million barrels per day (bpd). Following the revolution this slumped to just 150,000 bpd by the middle of 2014, but there has since been a recovery to around 1.1 million bpd.

Most of the oil facilities are in the east of the country and are therefore now in the hands of Haftar. For countries like Russia there are obvious advantages to backing the man in physical possession of the assets. Russia monetary losses were huge when the Gaddafi regime fell and now it wants to compensate for that. One MP in Moscow’s Duma told Pravda that Haftar gave Russia the potential to triple the $4 billion in oil and military contracts that Moscow lost with the death of Gaddafi.

Italy’s multinational oil and gas company Eni, and Total of France are engaged in joint ventures with Libya’s National Oil Corporation. This has proved more a source of division than of unity between their governments. Matteo Salvini, the deputy prime minister in Italy’s populist right-wing coalition government in power until recently, declared, ‘In Libya, France has no interest in stabilising the situation, probably because it has oil interests that are opposed to that of Italy’. He accused the French government of responsibility for chaos and the subsequent refugee crisis through encouraging the conflict, stating ‘we won’t be taking any lessons in morality from Macron’.

The refugee crisis

Yet the most momentous aspect to consider of Gaddafi’s legacy – and certainly the one that has sent the greatest shockwaves through European politics – is the degree to which his removal provoked the refugee crisis. He himself foretold this. When the Western bombing began, he declared, ‘Now listen, you people of NATO. You’re bombing a wall which stood in the way of African migration to Europe and in the way of al-Qaeda terrorists. This wall was Libya. You are breaking it.’

As I covered the fall of the regime in 2011, I was told about officials of the secret police, the mukhabarat telling criminal gangs that they could resume their people smuggling operations. Subsidies from the European Union to Gaddafi’s regime had previously served as an incentive for officials to block this. Now he was gone, there was no incentive anymore.

During one of my visits, two years ago, I met Zouhar, a young man of 23 from an impoverished background, who had bought land, a house for his family, and a new car for himself as a result of people trafficking. This was a modest reflection of his earnings, which were no less than $200,000 (£129,000) a month. Further along the coast, in Garibouli, 38-year-old Hamza was also making serious money – just over $160,000 a month. He hoped the figure would rise further once he found a source of cheaper motorised dinghies for his human cargo, who he charged around $1,000 a head. My most recent visit to Libya took me to Misrata, Libya’s third largest city, and a major centre for the detention of refugees and migrants.

I first met Ramzi Abdurahman, an officer in one of the patrol boats when Misrata was under siege with daily shelling and air strikes, in the early days of the uprising, and then again after the regime fell. On this visit we reminisced about all that had happened to Libya since the heady days of the revolution in Libya and the promises of the Arab Spring. Sitting in a country that had gone from a pariah state to a failed state, sending shockwaves through Africa and across Europe, we talked about the moment when Gaddafi’s death seemed to promise a bright new future. As we talked about seeing those bodies lying on the warehouse floor, Abdurahman reflected, ‘All that seems to be such a long time ago. We thought everything was going to change, everything would get better’. He reflected for a moment. ‘Now we have to live with reality and reality is not easy in Libya. Maybe Saif al-Gaddafi will be back. People remember the past they want.’ He took a sip of tea. ‘Anything is possible.’