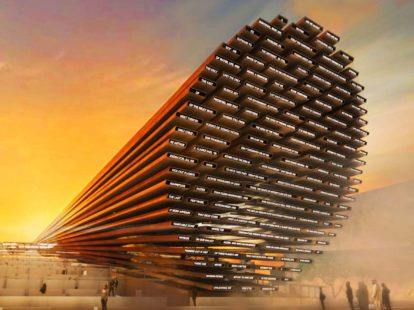

Jake Meyer started rock climbing aged 12. Two years later, barely into his teens, he declared that he wanted to become the youngest person to climb the Seven Summits – the highest mountain on each continent. It’s a precocious goal for a 14-year-old, but he ticked them off – including Everest and Antarctica’s Mount Vinson – and held the record by the time he was 21.

In 2009, Meyer set his sights on K2, the highest point in Pakistan and the Chinese province of Xinjiang, and a mountain so treacherous that for every four successful summit attempts, one person has died. It was described by Italian mountaineer Fosco Maraini as “just the bare bones of a name, all rock and ice and storm and abyss. It makes no attempt to sound human. It is atoms and stars. It has the nakedness of the world before the first man – or of the cindered planet after the last.” Meyer reached 7,700 metres before turning back due to adverse conditions. Seven years later, now 32, he returned to one of the most dangerous mountains on Earth. We asked what drew him back.

“Just the bare bones of a name, all rock and ice and storm and abyss. It makes no attempt to sound human.”

Fosco Maraini describing K2

I remember trips to Rouge-mont, a village near Gstaad, when I was five or six. There was a mountain behind the village, Le Rubli, that we would go and climb every year. Towards the top of it, there were even some little sections of via ferrata, old chains and things in the rock. I can just remember going up there and having this extraordinary sense of being out in an environment where you felt incredibly small. I can’t actually remember getting to the top of Le Rubli, but it was always there in the back of my mind as something that would be special to achieve.

I’ve always found motivation in the challenge itself, and in setting myself progressively bigger goals. I’m unashamedly attracted to ticking off lists. Whether or not it’s a formal challenge like the Seven Summits, or a looser set of objectives strung together, I love the idea of creating a connection that forces you to go to places you wouldn’t necessarily have chosen. It creates an incredible diversity of experience. There are many 6,000-metre mountains to climb, all over the world, and when I travelled to Argentina it became so much more than just Aconcagua; experiencing the culture of the environments in which these mountains reside is a part of the adventure.

In many ways I still have that same youthful sense of invincibility that I had when I was 14, wanting to climb Everest. The absolute belief that it will never happen to me, that it will always be somebody else. However now, being a father and a husband, I’ve come to realise that it’s about so much more than just my dreams and aspirations, even if that’s still what drives me. Has that specifically made me take fewer risks? Probably not. Has it made me more aware of the risks? I think absolutely. And it’s twice, or three times, the reason to come home safe.

“The statistics for K2, nearly a one in four summit-to-death rate, it’s worse than Russian roulette.”

Jake Meyer

I’ve been in some scary situations, but I can’t put a finger on a moment in the mountains when I’ve been genuinely scared. And I’ve seen many others around me being fearful, and making poor decisions based on that emotional reaction. So a healthy respect for the environment is vital, rather than blind optimism or an absence of fear. I’ve heard it said – especially in the military – that you want to feel the frisson of the moment. Those who have no fear, they’re the ones that get killed or do stupid things. And I think it’s very similar for those of us operating in these extreme conditions: respect the environment, but treat it like any other risk. Do everything you can to decrease your vulnerability, to mitigate against the risks, but don’t let them stop you from getting out of bed in the morning.

If you look at the statistics for K2, nearly a one in four summit-to-death rate, that’s worse than Russian roulette. But that degree of risk has also been part of the attraction for me, especially with K2. If it was just any other old mountain, I wouldn’t be that interested in it.

Jake Meyer is a British mountain climber and motivational speaker.