There’s no such thing as the perfect world map. For centuries, cartographers have struggled with the basic but unavoidable disparity between a flat representation and a globe. Map projections are essentially a series of equations, much like the code behind a pretty-looking webpage. However, the argument goes that cartography is essentially subjective, with maps representing the political ideals of their creators.

The most notorious is Gerardus Mercator’s projection of 1569 – the map many of us will remember fastened to classroom walls during childhood. It’s still used by Google Maps today. Mercator’s projection distorts the size of regions depending on their distance from the equator. Any more than a quick glance will reveal its absurdities: Greenland is presented as roughly the same size as the African continent and Antarctica resembles a creeping mass of icing sugar as wide as the image itself.

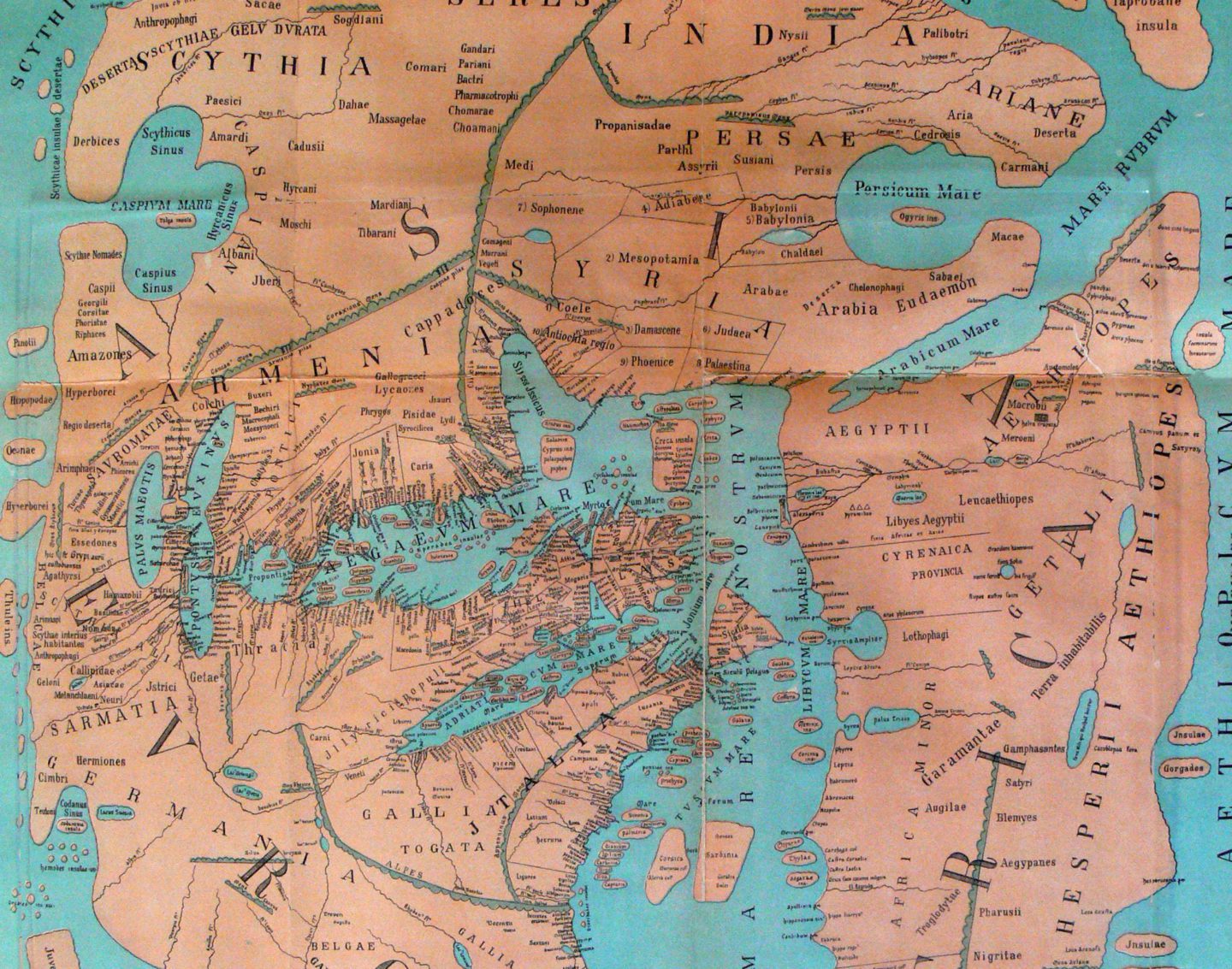

Konrad Miller 1898 "Orbis habitabilis ad mentem Pomponii Melae" Mappaemundi, Book VI. "Reconstructed cards" panel.

According to the late German filmmaker Arno Peters, this warping of land mass was a deliberate attempt by the West to belittle the global significance of developing countries. It was, essentially, a racist map. Defenders of the Mercator projection will argue it was primarily intended as a tool for European mariners, who followed its lines of constant compass bearing.

The Gall-Peters projection, presented by Peters in the early 1970s, attempted to redress the balance. A cylindrical equal-area projection, it more accurately represents land mass in the southern hemisphere, roughly double that of the north, but also suffers some distortion horizontally near the Poles, as well as vertically at the equator. Currently there is no one particular projection used across the board in UK schools, with teachers encouraged to explore a range of formats with their pupils.

The ancient Greeks and Romans placed the Mediterranean at the core of their maps; their immediate environment was quite literally the centre of their universe. Modern cartographers don’t have the luxury of ignorance. They have a difficult choice to make: do you misrepresent size or shape?