In 2008, Lance Corporal Hangam Rai was patrolling in Helmand province in Afghanistan – a Taliban stronghold that saw some of the fiercest fighting of the war – on a routine mission to resupply a nearby checkpoint. Since the beginning of the conflict in 2001, improvised explosive devices (IEDs) – munitions converted for use as road-side bombs – had become the weapon of choice for the Taliban-led insurgency, and were responsible for 66 per cent of all coalition deaths in the war.

The patrol was on edge, progressing slowly and scanning the ground ahead. At one point, having seen something suspicious, the commander – riding in the first of four armoured Land Rovers – ordered the patrol to stop and Hangam and his colleagues to dismount and search for hidden IEDs.

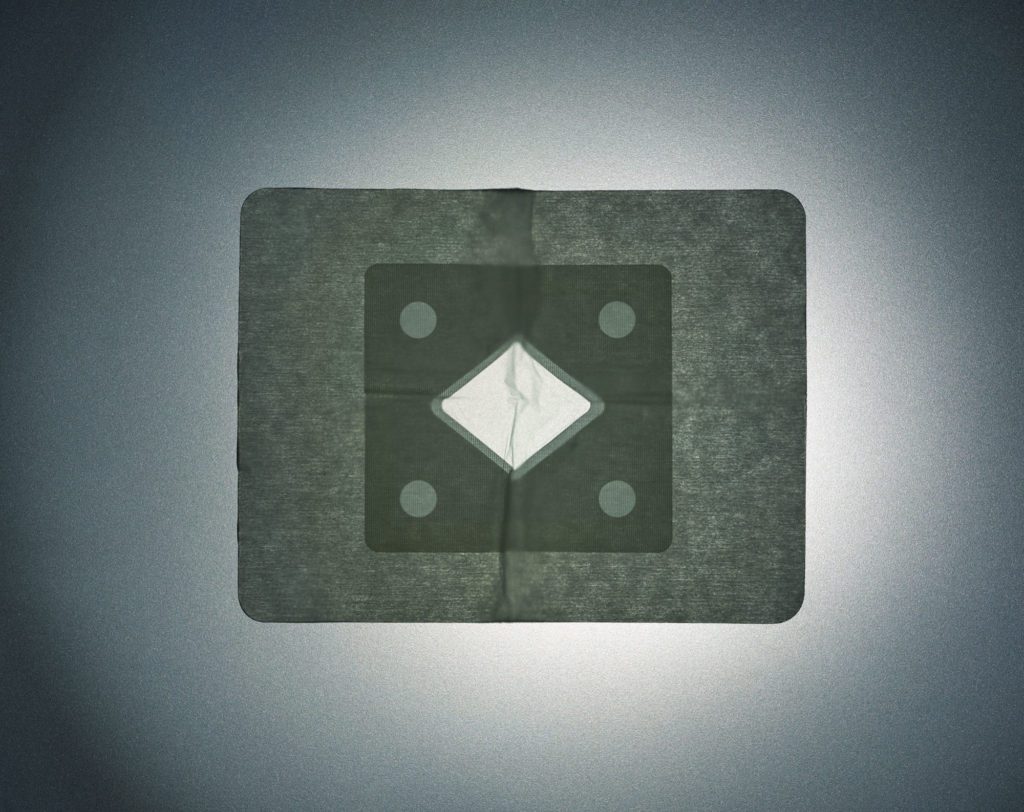

Cello Gauze: If you’re on patrol and one of your unit is shot, you don’t rush straight to them – you don’t want to get yourself or someone else injured. Once we have assessed the situation, and it is safe to approach, we follow a procedure called CACBD, which stands for catastrophic bleeding, airways, circulation, breathing and disability. Every soldier carries a personal first aid kit containing two tourniquets that they are trained to use on themselves or another soldier, but they are only suitable for injuries or amputations where some of the arm or leg remains. If you have a wound to your neck or torso we have to use Celox. This is a gauze that has been impregnated with chitosan, a clotting agent derived from crustacean cells, that we pack into the wound and that can stop severe bleeding in as little as three minutes. Before this we used the American QuikClot powder, but if you ripped open a packet with your teeth and inhaled it, or it went in your eyes, you could be seriously injured yourself.

Hangam was 10 metres away from the commander’s Land Rover when it slowly edged forward, detonating an IED. It was a massive explosion, ripping the first vehicle in half and throwing the gunner 50 metres away. Hangam, miraculously, was unhurt, but the driver of the vehicle suffered the loss of two limbs and the commander, who was stripped completely naked by the blast, sustained serious internal injuries.

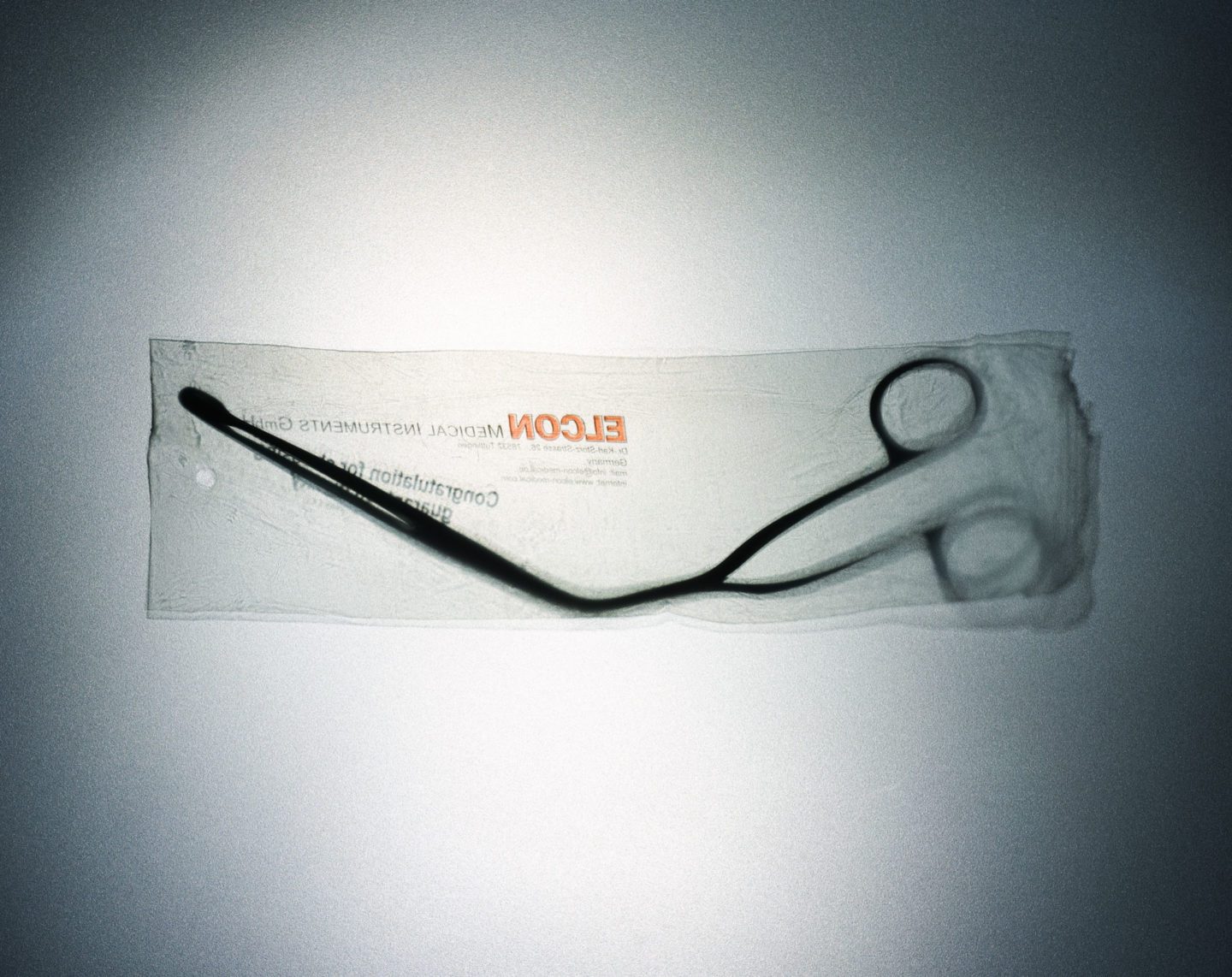

Forceps: We use these for areas that are hard to reach, such as down the windpipe. In a battlefield situation, however, I would use my hands because it would be quicker.

As the combat medical technician for the company, this was the multiple-casualty, mass-trauma event that Hangam had been training for. His quick actions that day – triaging his patients, directing the other medics in his team and coordinating the evacuation – saved the lives of both soldiers. But it was close – the emergency evacuation helicopter arrived in less than half an hour. “If it had been delayed by five minutes,” Hangam says, “the commander would not have survived.”

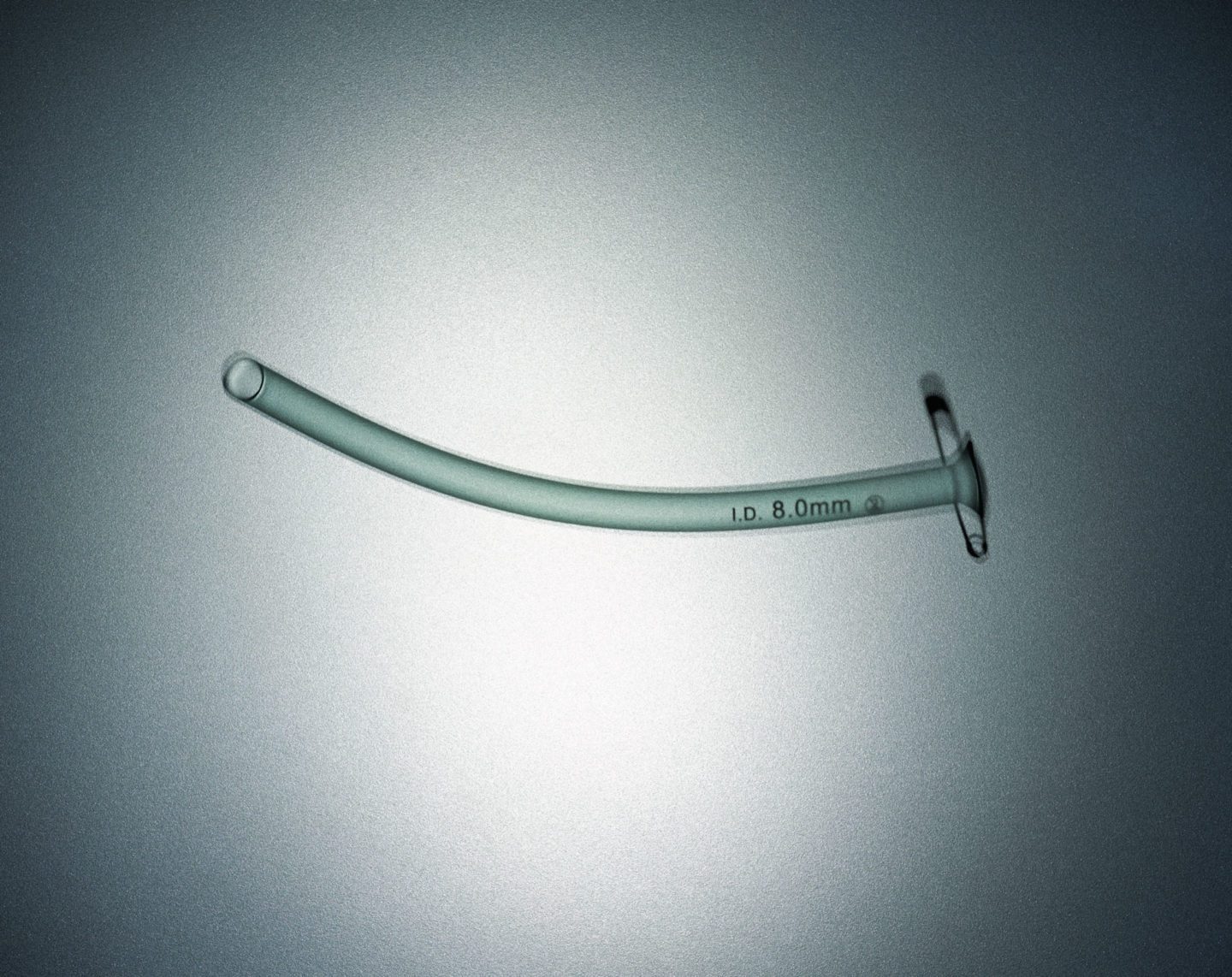

Nasopharyngeal Airway: Once we’ve controlled the bleeding we move to the airway. If the casualty’s mouth is blocked, we use a nasopharyngeal airway to open the passage from your nose to the trachea. I carry two sizes – to work out which one to use I measure the tube against the casualty’s little finger, as it’s normally a similar size to your nostril. We also carry an oropharyngeal airway, for the mouth, though it is better to go through the nose as this doesn’t run the risk of making the casualty gag and vomit.

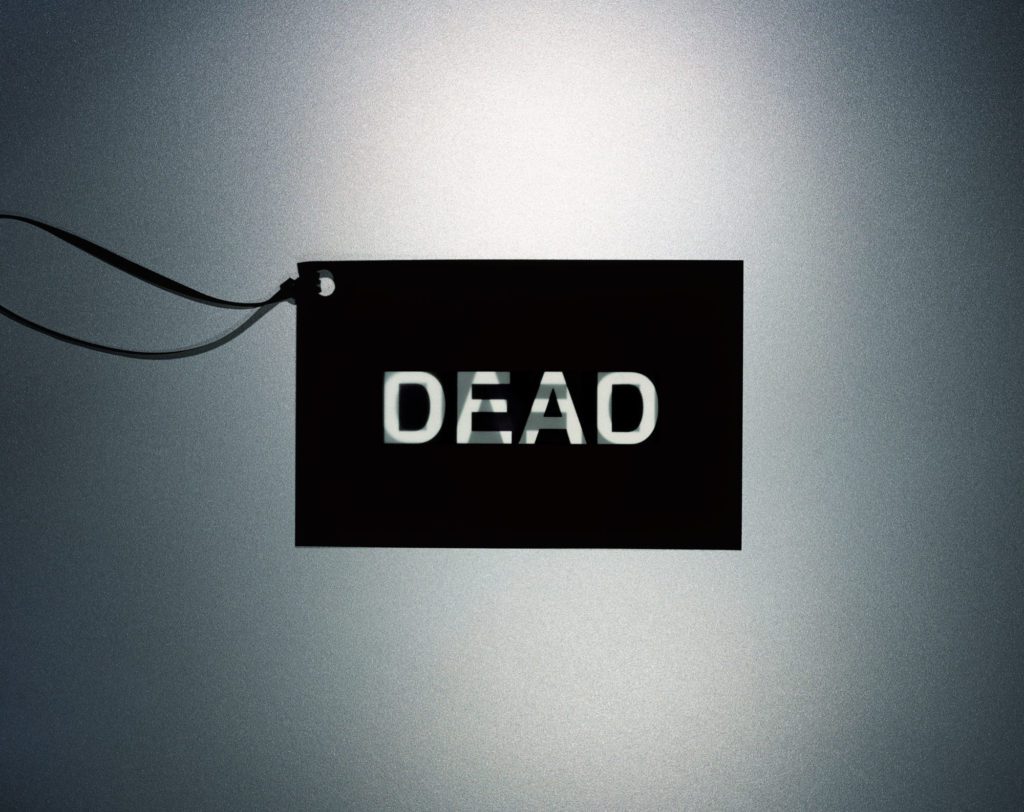

As the war in Afghanistan continued, the modified Land Rovers were replaced by more robustly armoured vehicles, and the kit carried by Hangam, who received a commendation for his actions, evolved to reflect the realities of modern insurgent conflict. And yet, although fatality rates have fallen for British soldiers – in 2015 a study found that around 265 casualties survived injuries that would have been fatal at the beginning of the war – these indifferent, utilitarian objects poignantly convey the brutal trauma of war.