On 15 April 1912, Alexandra David-Néel met the Dalai Lama while he was living in exile in British Bhutan. She was the first Western woman ever to do so, yet with a striking lack of humility she declared that the Dalai Lama’s desire to see her was ‘even more strong than mine to see him!’ Maybe she was right.

The fierce five-foot Parisian was extraordinary by any account – a Buddhist scholar who had at one point made her living as an opera singer, she first ran away from home at the age of five. In her introduction to My Journey to Lhasa she described how as a girl she had stared longingly at railway tracks imagining where they might take her, ‘I dreamed of wild hills, immense deserted steppes and impassable landscapes of glaciers!’

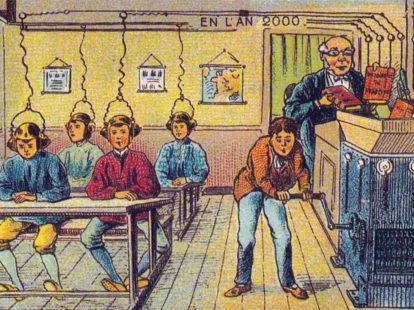

David-Néel and her adopted son, the lama Aphur Yongden.

By the time she died – just one month short of her 101st birthday – her vivid, often humorous writings on Buddhist practices had inspired beat writers Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg, and attracted the admiration of Lawrence Durrell. Durrell, renowned for his testing intellect and complex relationship with the opposite sex, interviewed her, and did not hesitate to describe her as ‘the most astonishing woman of our time’. Certainly she was extremely brave: to travel through Tibet at a point when foreigners were banned, she disguised herself as a beggar, dyeing her hair with Chinese ink and concealing a revolver to protect herself from robbers and wild animals. The esoteric, spiritual nature of what she observed inevitably raised sceptical eyebrows, but there was little doubt about her dedication to understanding lamas who claimed to survive naked at sub-zero temperatures, command spirits, and be able to fly.

‘She disguised herself as a beggar, dyeing her hair with Chinese ink and concealing a revolver.’

The woman who stares out forbiddingly from later photos, wearing a Tibetan rosary and Buddhist peaked hat, was born just outside Paris to a Frenchman, who was a Huguenot Freemason, and his Belgian Catholic wife. She experimented with Christian asceticism as a girl, while indulging her taste for adventure by reading Jules Verne’s science fiction novels. By the time she was eighteen, she had travelled to England to pursue studies of the occult – including theosophy with the notorious Madame Blavatsky – and was well known both as a feminist and an anarchist. An unexpected inheritance meant that at the age of 23 she was able to travel for more than a year through Ceylon and India, which began her lifelong love affair with Asia.

But then the money ran out. She returned to Europe and embarked on her brief career as a touring opera singer, before becoming the artistic director of the Tunis casino. Here she also began a love affair with Philip Néel, chief engineer of the railways in Tunisia. It was a marriage of convenience – they eventually married in 1904, but it was perhaps unsurprising to both of them that she could not settle down. In 1911 she travelled to India and Sri Lanka again.

This was the trip that proved her greatest turning point. She had a love affair with the young reforming Maharajah Sidkeong Tulku Namgyal in India, which ended tragically in 1914 when he died of suspected poisoning. She also visited the ‘Bo Tree’ (propagated from the original fig tree where Buddha received enlightenment), secretly watched erotic Tantric rites, and was inspired by her meeting with the Dalai Lama to make the precarious journey to Tibet’s capital, Lhasa.

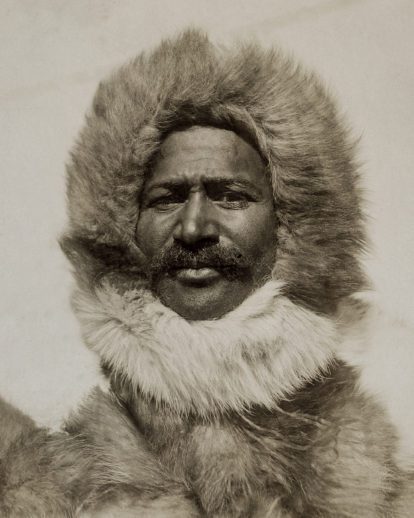

British secret services dubbed Alexandra David-Néel the ‘French nun’ as she travelled across far Eastern landscapes.

In response both to sceptics and to those who asked her to perform occult tricks on her return to Europe, she wrote, ‘Tibetans do not believe in…supernatural happenings. They consider the extraordinary facts which astonish us to be the work of natural energies.’

She would make five visits to Tibet in the end, overall spending fourteen years there. Much to her husband’s irritation, her companion for her travels was Aphur Yongden, a 15 year-old lama – in 1929 she made him her adopted son. One of their most significant encounters before crossing the border was with the stout and menacing Lachen Gomchen Rinpoche, with whom she studied. She described him ‘with all the trappings of a magician: a five-sided crown, a rosary necklace made of 108 round pieces, cut out of so many skulls, an apron of human bones bored and carved, and in his belt the ritualistic dagger (phurba).’

David-Néel’s writings (she wrote 25 books) became most notorious for their focus on Buddhist meditation techniques to generate heat for surviving extreme cold, levitate, and send telepathic messages. Yet the woman herself was just as much a source of fascination as what she observed – not least to the British secret services, who dubbed her the ‘French nun’ as she travelled across dangerous landscapes to visit Oriental princes and lamas. Like all the greatest historic figures she was an individual of contradictions: a self-proclaimed scholar who was hazy on dates and places, an original who stole others’ ideas, a champion of Buddha’s compassion who simultaneously railed at the harshness of this life. But most importantly she diligently chronicled a vanishing world at a critical moment in its history, becoming in the process one of the twentieth century’s most significant and fascinating explorers.