A man stands in front of a large screen that depicts a picture of leopard-skin on the left and a rhinoceros on the right. He is seen as one of the most powerful figures in Artificial Intelligence, yet on stage he projects an understated charisma with his eruption of dark curls, loose grey shirt, black trousers and donnish glasses. ‘You should always start a talk with a decent joke,’ he says in French. ‘So I had a look around and found Aristotle’s quote that beings are created from ‘matter’ and ‘form’.’

‘What is it that makes the difference between an inspirational composition, and something that’s, well, more like the musical equivalent of a leopard-skin rhinoceros?’

The audience laughs as he drily quips that he’s not very good at jokes. Then he gestures to the pictures of the leopard-skin and the rhinoceros. ‘Today,’ he declares, advancing the analogy to music, ‘we have the technology that allows you to separate the two…and if you can separate them, you can put them back together.’ In consequence, he continues, it’s possible to put together ‘matter’ [the harmonies, melodic sequences and rhythms of music] and ‘forms’ that didn’t necessarily go together before. On the screen behind him, a leopard-skin rhinoceros appears.

The man is Francois Pachet, one of the world’s foremost experts on applying AI to music. At the start of 2017 – when he gives the talk at a technology conference just outside St Malo – he is Director of the Sony Computer Science Laboratory in Paris. Just months later, he will be poached by Spotify to head up their Creator Technology Research Lab, prompting an explosion of paranoid speculation that this is the first step to replacing artists with machines. ‘Francois Pachet has the capacity to change the music industry as we know it,’ declares one commentator. The observation is not a compliment.

Avaunt talks to Pachet in Paris, and finds him dismissive of the hysteria. ‘People can always have fears,’ he declares. ‘I have exactly the opposite feeling – when you have new technology it opens the door for many more people. It’s just like the reaction in the Eighties when the first samplers arrived on the market, meaning you had a keyboard that could recreate the sound of a piano, guitar or orchestra. Before that you had to rent a piano, pay a cellist, hire a studio – people said this meant the end of music, but in fact more musicians were able to experiment and create works that were more interesting. So I don’t feel any danger – on the contrary, I think this could generate more sources of revenue for artists.’

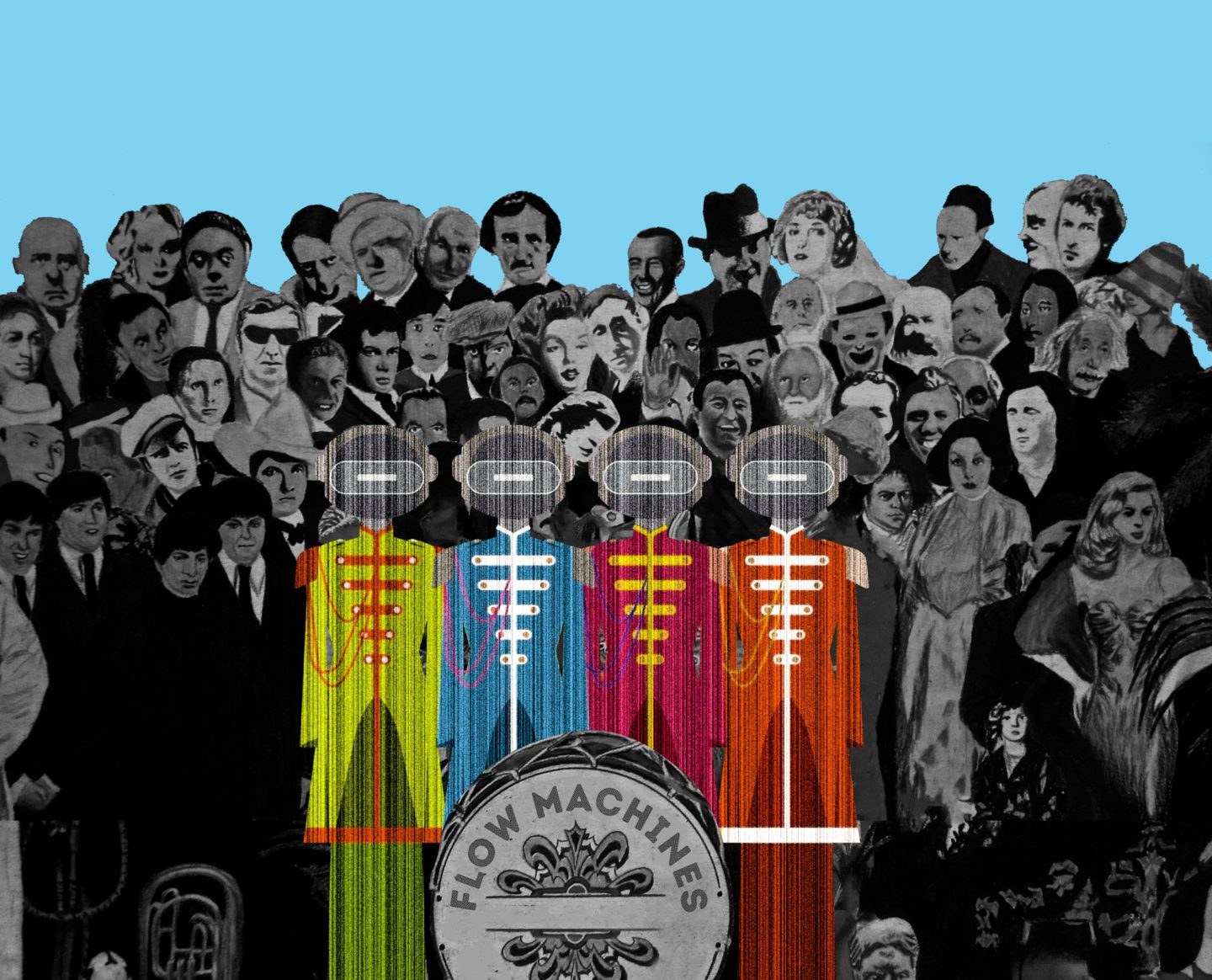

At Sony, Pachet was the co-ordinator of Flow Machines project, which was funded by the European Research Council to create the most cutting-edge algorithms for collaborating with musicians and creating new music. Flow Machines is an advanced neural network that analyses a database of existing songs, by, for example the Beatles, identifies the harmonic progressions and melodic sequences that characterise them, and then uses this knowledge to produce new work. There are many other companies working their way towards the Holy Grail of making computers produce convincing music: the London-based Jukedeck; Google Brain’s Magenta; Melomics (a Spanish company which claims to be based on bio-inspired algorithms); and Google DeepMind’s Wave Net. Amid the current eruption of interest in creating music with Artificial Intelligence, what is it that makes the difference between an inspirational composition, and something that’s, well, more like the musical equivalent of a leopard-skin rhinoceros?

‘There are interesting technological aspects to all of these projects – AI itself is exploding, and every day brings a new academic paper or result,’ Pachet says in reference to the AI music being produced by competitors. ‘But that’s not what inspires me. Musicians are my primary source – I’ve always been obsessed by the mystery of composition, what makes a melody work, how you create a simple motif. Is a piece of music compelling, do you want to listen to it again and again? I studied a lot of music, including classical guitar at conservatory, and I think this gives me better insights into how to model this with computers in a smart way.’

‘People can always have fears. I have exactly the opposite feeling – when you have new technology it opens the door for many more people.’

Francois Pachet

Yet the rapid advances in AI sophistication – even in the last couple of years – are also making a crucial difference. After all, machines have been used to compose music since the Fifties – famously the composer Lejaren Hiller used a computer to generate The Iliac Suite for string quartet in 1957.

‘There have always been waves of development in Artificial Intelligence,’ says Pachet, ‘they were strong in the Sixties, receded in the Seventies [in a period known as an AI winter], surged in the Eighties, and then receded again. Right now we are on top of a wave that’s going to last for some time. The current trend is connected with advances in algorithms for tasks involving recognition and prediction, such as you see with automatic cars.’ (Other recent AI breakthrough areas range from cancer detection to helping police make arrests through predicted crime patterns.)

While certain elements of the media love to drive a narrative of fear, in which the subtext is that robots will one day take over from humans, AI insiders declare that their work is all about the augmentation of human ability. Pachet explains that this is particularly true in music, pointing out the intensely collaborative aspect of Flow Machine.

‘We are working with some very exciting musicians,’ he says. ‘We start by asking them about their favourite style of music and favourite artists, feed these into the machine, and the machine will generate a new score. Then we pick which aspects work well and which are a bit boring, and ask the machine to generate a solution – you really need a curator who can shape the process. It’s intense, and it’s tiring, but also very exciting.’

‘Certain people have enough imagination to create songs without any help,’ he continues. ‘But for any musician who’s interested in working with computers, this is the future. The new AI singles we have released have been made possible because of real artists, and I think it is a landmark. The dream is simply to make great songs.’

Yet there has to be something beyond this. What does he think will happen further in the future? ‘It would be interesting to do something that AI can that humans do not,’ he concedes. ‘We could generate new formats for songs – currently most songs last around three minutes, but there is no reason for that. You could imagine a song that lasted for 20 seconds, or three days, or even one week. Maybe it’s a bit early to talk of such things, but there will be a lot of changes in the years to come.’