Judit Polgar’s father, Laszlo, decided she would be a genius before she was born. In 1970s Communist Hungary – where there was a chessboard in every household – the educational psychologist set out to prove the theory that brilliance was not something innate, but something that could be instilled by intensive one-on-one tuition from early childhood. He and his wife, Klara, agreed to practise the theory by home-educating their children to be chess champions – in a biological coincidence that still resonates today, all three happened to be girls. While her elder sisters, Susan and Sofia, achieved the titles of Grandmaster and International Chessmaster respectively, Judit stunned the world when she beat the record of chess legend Bobby Fischer to become the youngest person ever to be made Grandmaster.

Despite her breakthrough, today, in the world of competitive chess, top-ranking female players remain as rare as the Sumatran tiger. In 2018 there is just one woman, Hou Yifan, in the top hundred Grandmasters, and of the 16,000 active players who registered with the English Chess Federation last year, only 4 per cent lacked a Y-chromosome. If there was the sound of glass ceilings smashing in 1991, when Polgar, then age 15, became Grandmaster, then they have been carefully pieced back together again, splinter by splinter. This despite the fact that Polgar herself (who has now retired from competitive chess) went on to win a succession of impressive victories at male-dominated tournaments, beating nine world champions, including, most famously, Garry Kasparov in 2002.

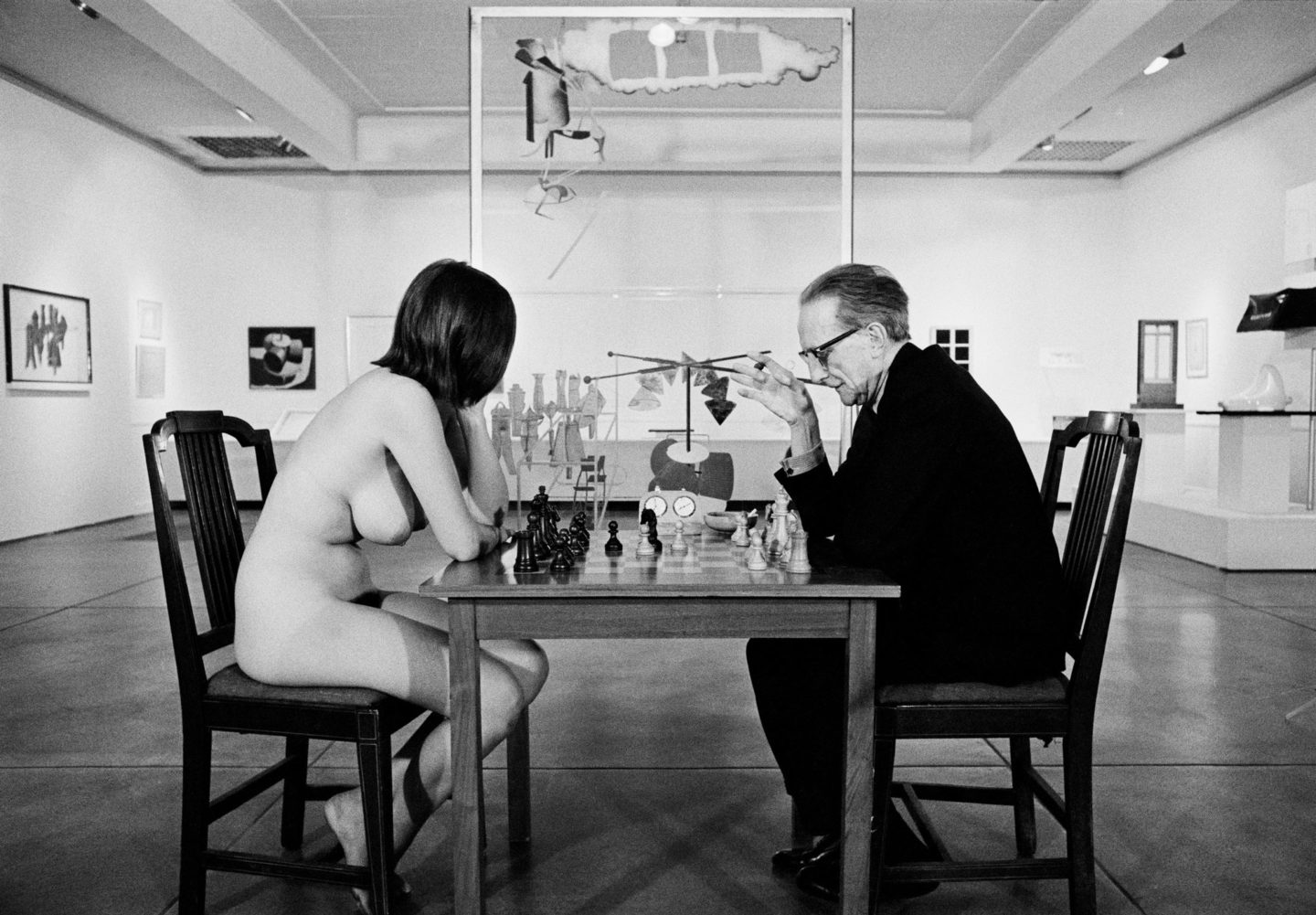

Above: Duchamp Playing Chess with a Nude (Eve Babitz), Duchamp Retrospective, Pasadena Art Museum, 1963. Photography: Julian Wasser.

The victory was particularly sweet because of a series of inflammatory statements Kasparov had made about women trying to compete in chess. In a 1989 interview with that bastion of gender equality, Playboy, he had declared, ‘Some people don’t like to hear this, but chess does not fit women properly…I think this is very simple logic. It’s the logic of a fighter, a professional fighter. Women are weaker fighters.’

Kasparov has since modified his views, saying that ‘There’s nothing stopping a woman from ascending the ranks and becoming world champion, but the talent is just not there yet.’ It’s a short-sighted concession, not helped by the fact that just over quarter of a century after the Playboy interview, British Grandmaster Nigel Short proved that prejudice was still alive and thrusting when he told New In Chess that, ‘One [gender] is not better than another, we just have different skills. It would be wonderful to have more girls playing chess, and at a higher level, but rather than fretting about inequality, perhaps we should just gracefully accept it as a fact.’

‘Victory over Kasparov was particularly sweet due to his history of inflammatory statements about women in chess.’

I call Judit Polgar in Budapest, where she is now an ambassador for the Chess in School project for the EU, as well as running her increasingly influential Global Chess Festival. When we talk about her defeat of Kasparov, she says, ‘Of course it was a great moment, a great milestone in my life. Not only did he refuse to be open to the idea that a woman might beat him, but when I was younger he said he didn’t think we would even play together.’ Asked at what moment she realised her upbringing was setting her apart from other girls, she replies, ‘I understood completely, from the age of six, that I lived in a very special family, with a very special daily routine. Though this was mostly clear, unfortunately, because my older sister got a lot of feedback, mostly negative, from the Hungarian Chess Federation and from the government. They were not happy that she didn’t go to school and that she was already playing against adult male competitors.’

It has become part of the narrative about women in chess to ascribe Polgar’s extraordinary success largely to her upbringing, as if it is by extreme tactics alone that women can achieve equality with male players. Yet if statistics about female players over the age of 12 seem to reinforce the idea that Polgar is an exception to the rule, those who have encouraged girls to play chess at primary-school-level have observed something rather different. Chris Fegan, Chief Operating Officer of the UK organisation Chess in Schools and Communities, tells me, ‘We teach girls and boys together as part of the curriculum, and at that age girls do as well as or better than the boys.’ Of the fact that men then go on to so vastly outperform women in the top hundred he says, ‘I haven’t got any answer to that. But I certainly reject the idea that it’s anything to do with brains or parts of brains.’

Fegan, an affable and articulate Mancunian with eyebrows that look as if they are starting to have a life of their own, has himself been brushed with controversy over the women in chess debate. This summer he was announced as the new Director of Women’s Chess for the English Chess Federation (ECF). Accusations of sexism quickly flew when it was revealed that a man had been given the role. Formerly the job had been held by Sarah Longson, who has represented Britain in chess at the Olympics, but after she resigned to dedicate more of her time to working with the UK Chess Challenge, the post fell vacant.

Above: Hou Yifan vs. Maria Muzychuk, Lviv, Ukraine, March 2016. Due to fears of cheating, games are played behind closed doors and are broadcast with a 30 minute delay. Image: Misha Friedman.

Doesn’t Fegan think it epitomises the problem for women in chess that the Director of Women’s Chess is a man? ‘I wasn’t part of the appointment process,’ he points out simply. He did, however, play a key part in getting the role established in the first place. ‘For a while I was strategic adviser to the Federation. I raised the issue of diversity with the board and eventually – and it took a while – we got a woman’s director post. After Sarah stepped down, a replacement wasn’t found, and the next thing we knew the board had decided to abolish the post completely. So that’s when I walked back into the game.’

Why does he think he’s ended up being one of England’s leading chess feminists? For a moment the eyebrows threaten to take off. ‘I’m not labelling myself that am I? That’s a loaded title.’ He reflects for a moment. ‘But if it means – in this context – that I want women in the English Chess Federation to have the same opportunities, the same funding – and that’s going to take a hell of a while for me to do that – and the same support mechanisms, and the same welcome as men, then yes,’ he swallows, ‘I am a chess feminist.’

* * *

There is nothing new about the idea of women playing chess. According to Marilyn Yalom, in Birth of the Chess Queen: A History, ‘A wealth of stories featuring women formed part of medieval Islamic fiction. These stories often took the form of a contest between the sexes, with the possibility that the winner might be a woman intensifying the excitement.’ She describes how in one tale, the beautiful maiden Zayn al-Maswasif invited Masur, a love-struck suitor, to play chess with a set made of ebony and ivory and encrusted with pearls and rubies. As they played, Masur became so obsessed with her fingertips that he was unable to concentrate on the game and was quickly defeated.

Eroticism is a repeated theme in the story of men and women playing chess together – according to one early 19th century picture, the intellectually highly able Madame de Remusat wasn’t above playing Napoleon in the nude. A more infamous twentieth century photo – described by the Smithsonian Archives of American Art as being ‘among the key documentary images of modern art’ – shows the author Eve Babitz playing Marcel Duchamp where he is dressed and she is naked. Reassuringly there is a strong line of historic women known to have deployed their wits alone to play chess too, including the great Renaissance patron of the arts, Marchese Isabella D’Este, Catherine de Medici, wife of Henry II of France, and Elizabeth I. Benjamin Franklin’s visits to Paris prior to the French Revolution were considerably enhanced by the opportunity to play chess with such socially elevated women as the Duchess of Bourbon, who was observed by Thomas Jefferson to be his strategic equal.

‘The cause of the present intellectual activity of our women-folk is due to the use of wire hair-pins. The wire hair-pins excite ‘counter-currents of electricity’ and bewilder the wearer’s brain with strange vagaries.’

American Chess magazine, September 1897

Some historians mark the dwindling of upper-class women playing chess from as early as the start of the 17th century. However there remain notable exceptions throughout, including an all-women’s chess club formed in Holland in 1847, or the Italian-British legend Louisa Mathilda Fegan (1850-1931), who also fought for women’s rights. They are, however, exceptions. By the end of the 19th century, women’s participation in chess was viewed flippantly enough for the September 1897 American Chess magazine to put forward an extraordinary theory:

Many conservative men (a fair correspondent avers they are brutes more or less) have strongly contested the claim that a woman could play a consistently good game at chess…They persistently declare that, though the play of this or that woman may be, at times, of a fair order, it is inevitably erratic, and subject to those illogical aberrations which science, as exemplified in chess, most severely frowns upon. Now, if there is any foundation for this charge, it is evident that the women’s game must be affected by some extraneous cause that does not influence the men, and there has been much puzzled inquiry as to what that cause can be. It has remained for the Troy Times to solve the great mystery. It declares, on the authority of ‘a great scientist’ – what a pity we do not know his name – that the cause of the present intellectual activity of our women-folk is due to the use of wire hair-pins…when ‘boiled down’ it amounts to this: that the wire hair-pins excite ‘counter-currents of electricity’, whatever they may be, and so bewilder the wearer’s brain with strange vagaries, and lead them to do whimsical things…So, in future tournaments, one of the rules governing the play should be: ‘All ladies-players are requested to wear shell hair-pins.’

Whether the article was tongue-in-cheek, or simply penned by a journalist slavishly following the cultural obsession with electricity, more than a hundred years later female chess players are no longer skewered with hairpin theories. But the more individuals I interview, the clearer it is that ongoing cultural perceptions still play a massive part in dissuading women from playing professionally – and that those bucking the trend often do so because they come from families with their own strong chess cultures.

I talk to Jovanka Houska, the 38-year-old British Women’s Chess Champion who has attained International Master and Woman Grandmaster status. Over a pot of fresh peppermint tea at London’s Delaunay, she explains the influences that have shaped her career. ‘It was a family hobby,’ she says. ‘My father – who was from Uruguay – learnt the game from his father and he learnt from his father – who was Czech – so my father was really adamant that we were going to play chess. He taught my brother first. Somehow it was an accident that I got involved. They wanted a filler for a chess tournament. I was five, and though my dad said “She’s too young’’, my mum said, “She can play”. I ended up winning it.’

Houska cuts a demurely glamorous figure, but there is no mistaking her steeliness. Fegan says, ‘Anybody who’s got to the level that she has has a) to have innate talent, b) to work extremely hard.’ They also have to have a thick skin when it comes to put-downs. Houska says, ‘When you’re playing as a kid the boys do put the girls down, they talk over the girls, I’ve had that happen a lot. Though I’ve had some funny moments when they say “you’re just a girl”. And then they play me, and then they lose.’

Illustration: Nathalie Lees

She continues, ‘I’ve had Grandmasters be very aggressive towards me, saying why do you play in this particular way, why don’t you do this? I played one individual where it was a complete draw, and he insisted on playing it to about 130 moves. There was one trick in the position. And once I’d defended that, most people would have agreed it was a draw. But he took it to 130 moves. Afterwards he turned round and said to me, “You deserved that”.

Houska’s ability to perceive such aggression with humour is demonstrated not least in her recent erotic novel The Mating Game (co-written with James Essinger), which features a heroine who can only sleep with men who have beaten her at chess. However, in a world which repeatedly asserts that maybe there’s something in women’s DNA that lets them down at the chessboard, she also makes it clear how important a strong support network is to help beat bullying and prejudice. After all, every male chess player – from Bobby Fischer to current World Chess Champion Magnus Carlssen – has ridden the equivalent of a psychological escalator which has allowed them to feel that, whatever their setbacks, it’s perfectly normal to get to the top. Women, by contrast, must scale a mountain of disbelief.

‘Recently,’ Houska continues, ‘I was talking to the mother whose daughter is the only girl in her chess club. She’s the only girl when she plays in tournaments. And she has no female friends in the chess community. Without friends she isn’t going to stick with the game. It’s not going to be fun for her. I saw her in between games playing on her iPad, playing some game, and I thought that is not acceptable. We should at least try to bring the numbers up and perhaps put her in touch with other girls.’

Fegan concurs that support mechanisms are crucial. ‘Family, friends – they all make an important difference.’ He also points out that while girls at primary school level flourish in chess classes when they’re on the curriculum, ‘they do not go to after-school chess clubs particularly. Why is that?’ It’s an interesting point, that demonstrates the degree to which girls do not see chess as part of their cultural identity. By contrast Polgar tells me that as she grew up, ‘One of the most important elements was that our parents were always saying positive things about our progress. They instilled a mindset in which you can always get better. Whoever did well – whether it was me, or one sister or the other sister – it was very clear we were extremely happy for each other. The family shared the success because it proved we were on the right track.’

If the culture surrounding chess at ground level needs to be reinvented – so that it is seen as normal and part of a healthy social life for girls to play the game – the culture for high-level competitors must also be addressed. For instance prize money for women is often much lower than that for men – the financial rewards for winning the Women’s Chess Championship are over a third less than for winning the World Chess Championship. Women especially therefore find it incredibly hard to earn a decent living if they devote themselves to being chess players. This in turn impacts on the time they have to train and study, which creates a vicious cycle.

During the weeks of researching this article, the individual I have been particularly keen to speak to is Yifan Hou, currently the only woman in the World Chess Federation’s top hundred players. After going through a series of dead ends to make contact, finally one morning I wake up to find an email from her in my inbox. In an interview with CNN last year Hou said, ‘It’s a very conflicting feeling for me, on the one hand, I should be happy and encouraged to be in the top hundred…on the other hand, it’s a little bit upsetting to see the huge gap between the two genders.’

Talking by Skype from Beijing she says, ‘I have travelled through different continents, from Asia to Europe to North and South America, to encourage more young players especially girls to participate. But I’m also fighting for women players to have the same system as men.’ Last year she created headlines when she deliberately threw a match at the Tradewise Gibraltar Chess Tournament, as a protest at mostly being made to play other women. Today she declares, ‘I want to look forward from that now, and try to tackle something that will lead to a promising future.

So what will create such a promising future? According to Jovanka Houska, ‘Chess needs to be improved at all levels – it can’t be just for the girls. It has to be for the women as well. When it comes to elite players in the UK I would like the English Chess Federation to enshrine a policy of affirmative action. So, for instance, women’s teams will always be sent with the best trainer that we can afford. And an open team will never come at the expense of a women’s team.’

Despite the obstacles they have faced, what shines through with all three of the women players that I talk to is their profound passion for the game. Hou talks about how as a girl she fell in love with the shapes of the chess pieces. ‘People think chess is aggressive,’ she says, ‘but they should see how it contains beauty, encourages artistic thinking, and helps with education skills.’ Polgar describes how when her father taught her to play, ‘It really went under my skin. He made games like spectacular puzzles, magical things’. In her book, Houska raves, ‘One of the many mind-blowing things about chess is that even after only about 15 moves or so, every game is unique…there are more possible games of chess than there are atoms in the observable universe.’ If – beyond more practical measures – young girls and teenagers can be persuaded of these magical qualities in chess, then it will be a significant step to creating a bold, new, and more gender-balanced future.