I first met Coco Firenze — a member of Congo’s colourful subculture, the sapeurs — in a French restaurant on the Congo River in Brazzaville. This is the capital of the Republic of Congo, a country stretching from this great central African watershed all the way to the Atlantic on the west coast of the continent. On the opposite riverbank, where the fishermen’s wooden canoes looked like dragonflies floating on the surface, stood Kinshasa, capital of the ‘other Congo,’ which is the troubled Democratic Republic of the Congo, or DRC. Often the two countries are confused, despite their dramatically different identities and colonial histories.

More and more women are joining La Sape dressed in men’s suits.

It was an arranged meeting, which had taken some time to sort. The sapeurs — members of the Congolese La Sape, an acronym for Société des Ambianceurs et des Personnes Élégantes, or Society of Ambiance-Creators and Elegant People — are aware of how they are seen by outsiders, and the way their ‘look’ has been featured by photographers, fashion companies, and most well-known of all, the 2014 Guinness advert. During my time in Brazza, as the capital is also known, I’d met a brilliant Congolese photographer, Baudouin Mouanda, who had worked with the sapeurs on numerous occasions, and commanded their respect. ‘To see their image in a magazine reasserts their profile; they want it, it makes them proud,’ he told me. ‘They are not doing it for money. It’s a passion; but increasingly, they also know that they can make a business out of the way they dress.’

Sapeurism has spread out of the Congo into other countries, where the origins and motivations vary. In Brazza, the old tradition stays strong as the rules are passed on to the next generation.

Sapeurs are therefore a fragile cultural phenomenon, and hard to find. As I was told the story, their very specific sartorial identity evolved out of the wartime years when Congolese soldiers were drafted to fight on European soil, and alongside French soldiers, in World War Two. The soldiers picked up clothes from France, their former coloniser, mixing up a Parisian swagger and style with wardrobes then abandoned or bequeathed by the departing colonisers, who left Congo in 1960 when the country gained its independence. Many of the first sapeurs were servants to these Europeans – distinguishing themselves from other Congolese with a strict code of conduct and set of rules. By dressing like their masters, they were challenging their superiority – it was an essentially rebellious gesture that continues to inform the spirit of the tradition.

‘You can’t say we copy white people. We take the clothes and wear them better.’

Jacques Palas

Year by year, sapeurism evolved into a kind of ideology. You’d find the ringleaders holding court at places like the city’s Poto-Poto Bar. In the late 1970s, the movement was popularised by the Congolese musician, Papa Wemba, who was considered the unofficial leader of what became known as La Sape, with the look migrating into Kinshasa, Paris and Brussels.

I was in Congo for ten days. I’d tried looking for them in the Marché Total in the heaving Bacongo neighbourhood, but in a city of 1.3 million, I soon discovered you’re not going to just ‘bump into’ a sapeur in a flamingo pink suit and crocodile-leather shoes. My introduction was instead arranged by a local photographer, Victoire Douniama. After some negotiation, we agreed that I would buy Coco and his friends a riverside lunch; in return, they would talk to me about the tradition of La Sape. If we liked each other, and my interest proved genuine, they might show me more inside their own neighbourhood, Mikalou, on the far side of town.

‘A sapeur should wear at least two colours, and never more than three at any one time. A sapeur needs to dress like a garden, to be bright, like a flower, and above all, eye-catching.’

The way sapeurs dance is all part of a ‘display’ to show off their style – often holding a pose for two, three seconds.

When I arrived, Coco Firenze — named after Coco Chanel and the fashion city of Florence — was enjoying a cold beer with seven of his friends who’d come along. There were two women and five men, all of them immaculately groomed, and dressed in suits with every kind of tie, from polka dot bows to pinned cravats. Coco was a barber, another was a butcher, another an electricity engineer.

Coco stood up and shook my hand with an old-fashioned gallantry – civility is an important part of a sapeur’s code of behaviour. Then he walked away from the table, did a dandyish pirouette and a curious ‘display’, clacking his heels, throwing his hips out to one side, and pausing to pose. ‘It’s not a dance; it’s just a hello,’ said Jacques Palas, another in the party (all sapeurs have theatrical pseudonyms — it’s part of the rules).

Coco, who was the best dressed in the group, wore a cashmere blended wool three-piece suit in a cream-and-yellow windowpane check, with beautiful hand-stitched lapels. He unbuttoned the jacket to show me the label: Yves Saint Laurent. It was one of seven he owned. ‘To be a great sapeur, you want about thirty suits,’ he said. His dress shirt was a crisp white, and his shoes a black leather, Louis Vuitton brogue (‘English shoes and Pierre Cardin are the best,’ explained another of the sapeurs, Roland de Londres). Coco’s aftershave — as significant as the way one wears one’s tie-pin — was Thierry Mugler (Palas preferred Nina Ricci). ‘Thirty-five years a sapeur,’ Coco proclaimed: ‘My father was a sapeur before me. My grandfather worked for a missionary, who gave him his first set of clothes.’

Sapeurs have two ways of dressing, explained Roland de Londres: formal attire, and casual (denim and shirts are fine, but the rules still apply). Occasions vary, but the best ‘displays’ are generally at weddings, funerals and street demonstrations when a group gets together and promenades through their local neighbourhood. Many members, like Coco, grow up learning the rules from their parents. Others join later, inspired by the respect the sapeurs command among the local people. This was Palas’s motivation, who joined in 1982 when he encountered a famous sapeur in the street: ‘He dressed very oddly, which was why people nicknamed him “L’Étranger” or The Stranger.’

‘Displays’ by sapeurs happen rarely – organised off-the-cuff for celebrations like holidays and weddings. A passport is a sign of sophistication among sapeurs – carried like an ‘accessory’, to assert the fact they are men and women of the world.

Recently, women have been able to become part of the association, including one of the first female sapeurs of the Congo, Messanie Grace, who joined our lunch. The women dress like men, with the same gamut of accessories: spectacles, canes, fedoras, pocket squares, cigars and umbrellas. Like the men, the hair must be worn short and neat, and they must be ‘well perfumed’. The most important rule, however, is around the use of colour. A sapeur should wear at least two colours, and never more than three at any one time.

‘A sapeur needs to dress like a garden, to be bright, like a flower, and above all, eye-catching,’ said Coco. ‘You need to be interested in fashion to understand sapeurism, and even then, it’s different,’ said Palas.

I explained how in the post-colonial west, there’s criticism that the sapeurs are just perpetuating the look of the colonial oppressor. The group threw back their heads in disbelief. ‘Sapeurism is an image of power,’ said Palas. The group explained it as a kind of peaceful protest, proof that even a poor Congolese is his own master. ‘White people only ever made the suits, but they never knew how to wear them,’ said Palas. ‘White people only wear jeans these days. That’s why you can’t say we copy white people. We take the clothes from them and wear them better.’

A couple of days later, they showed me how. It was a Saturday, and I met them on their home turf — the same men and women from the lunchtime party, plus ten or fifteen more. The streets of Mikaolou were heaving with green taxis and market sellers, the footfall throwing up clouds of dirt and dust. Kids were playing soccer with homemade footballs, among open sewers and goats grazing on heaps of trash. Coco emerged from his premises — a one-room barber’s shack with a couple of chairs.

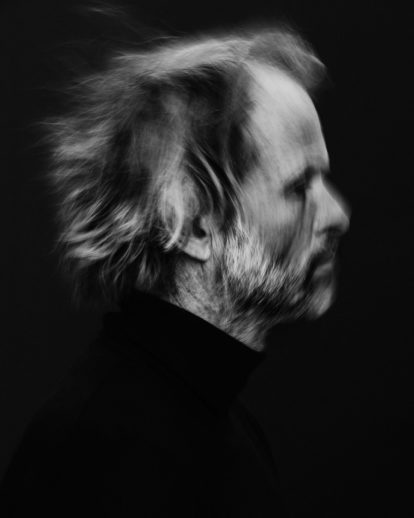

Personal grooming – one's haircut and choice of scent –matters as much to a sapeur as the label of his or her suit.

It was edgy. As I followed the sapeurs through the streets, the traffic slowed, and bus drivers blew their horns in respect at the display. We stopped at a makeshift bar, and I bought a few rounds of beer. We danced to a loud speaker system, among friends and family, and then an hour or two later, left to parade through the main marketplace, to an almighty cheer. I was walking behind Bifouma, a magnificently dressed grandmother, with hair dyed in the colours of the Congo flag, her neat waist pinched with a perfectly tailored suit in lipstick red. Her two young grandsons were primped and preened in suits; they moved through the street, pirouetting and jiving, as if they were dancing to music inside their heads.

It was a perfect example of how the sapeur tradition works as an act of defiance. The boys were orphans, and Bifouma wanted to teach them pride. That’s why they had all joined La Sape. It was a way of simultaneously escaping and challenging the problems life had thrown at them.

‘The roars of the crowd as they swayed in the Congolese sunshine, their chests blown out, the colour of their suits an explosion in the African dust.’

Bifouma, I discovered later, ran a market stall that sold second-hand shoes. It was located close to where the charcoal sellers, who are the poorest of the poor, peddled their wares. Yet the sense as we walked past was not of hardship but of celebration. As Bifouma’s arms waved in the air, her friends reached out their hands to touch her and cheer her on.

With the procession moving around them, Bifouma and her boys paused for a while, strutting and dancing like peacocks. The roars of the crowd as they swayed in the Congolese sunshine, their chests blown out, the colour of their suits an explosion in the African dust.

Sophy Roberts travelled as a guest of Journeys by Design.