At the very end of last year, army captain Louis Rudd became the first Briton to make a solo crossing of Antarctica using muscle power alone. Two days beforehand the American endurance athlete Colin O’Brady also defeated significant odds to complete the 1,000 mile journey successfully. Rudd partly took on the challenge to commemorate his close friend, Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Worsley, who died crossing the Antarctic in 2016, just 30 miles from his destination.

In order to tackle the immense physical obstacles, Rudd had to make several critical calculations about the weight of what he could take: key decisions ranged from having just one set of underwear to spending £5,000 on a specially-designed pulk to carry his equipment and food. As part of our focus on Antarctica in this issue, I went to visit Rudd at his home to talk to him in detail about how he had endured a journey that has defeated so many. He looked lean – he had lost 17% of his body mass during the trek – but though he seemed relieved to have completed the expedition, there was also a strong sense that he was figuring out the next challenge. In order to get as precise as possible an idea of what he had just survived, I asked him to talk me though how the journey had impacted on each part of his body. This was his response: a no-details-spared anatomy of how to survive the extremes of one of the world’s most hostile landscapes.

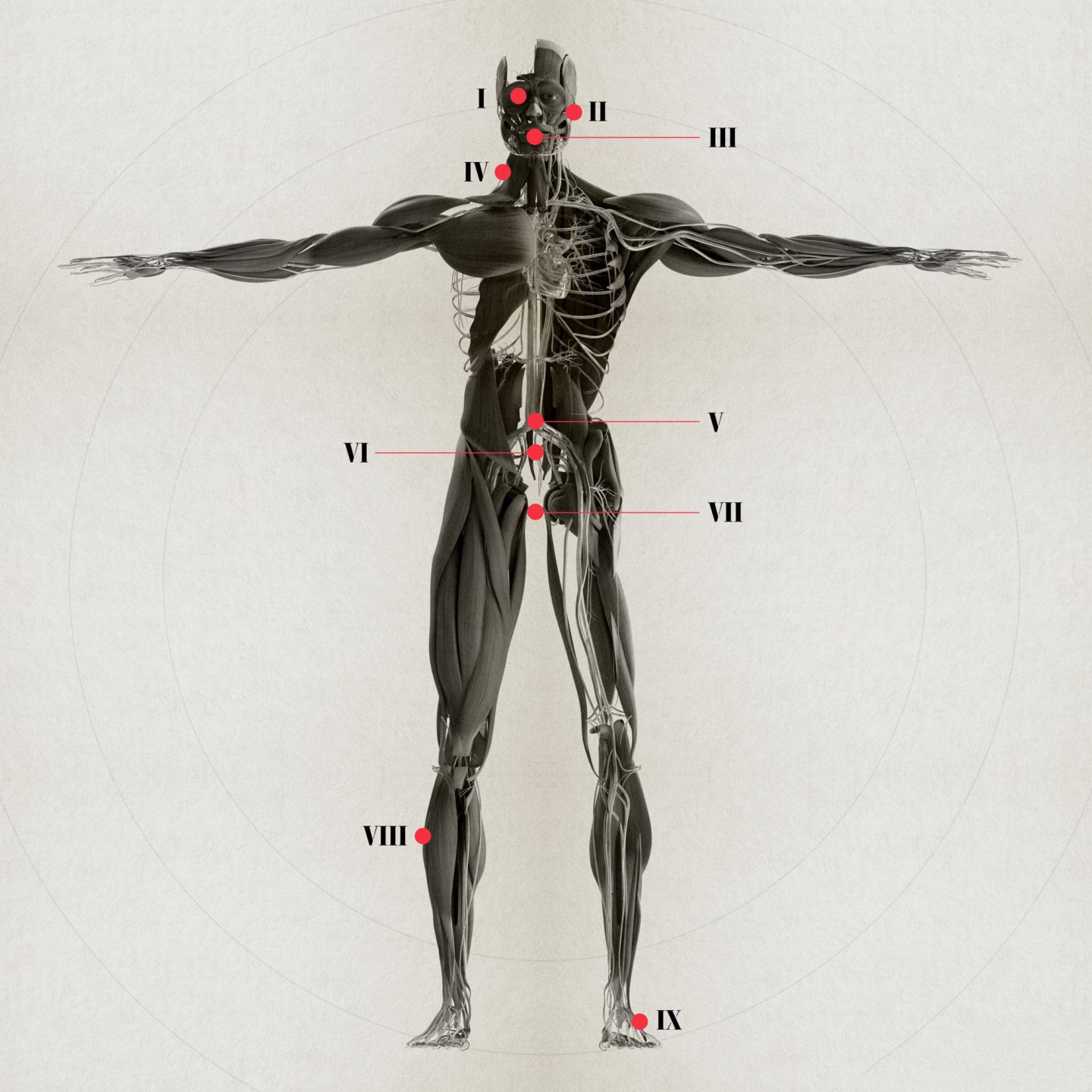

I

Eyes

You’ve got to be really careful with snow blindness. Antarctica is probably one of the worst places in the world for it – I was there at the time of year when it’s 24 hours of daylight. The reason there’s so much UV light is because the sun reflects off the ice sheets. Snow blindness is what happens when the sun burns your eyeball, which is just as painful as it sounds. The first warning signs are that you feel as if you’ve got a bit of sand in your eye. If you have a couple of hours without goggles or sunglasses there on a bright day, you’ll start to get signs. So, when I was outside the tent I always had goggles on. I had a pair of sunglasses with me too, but I ended up just wearing the goggles the whole time because they provided full protection around the edges as well.

II

Ears

Ears are really prone to frostbite. Not much blood flows through the tops. Some days I had just the face mask on, but not necessarily a thick hat. If they were too exposed to the wind, I would get a burning sensation, so I would grab a hat and pull that on. On the milder days – around minus 20 – I wouldn’t want a hat on because of the problem of over-heating. Instead I would wear a headband to cover my ears.

III

Mouth

On the days when it was in the minus 30s with a headwind, I would cover everything up, so I wouldn’t have any exposed flesh, apart from my lips. People do try covering their mouth a bit, but they end up with a massive ice build-up because of all the moisture that comes from your breath. I’ve never had a problem in the past with my mouth and lips. But quite a way into the journey, my immune system got a bit run down.

I got into the tent after a 12/13-hour day and noticed there were massive sores, both on the outside of my lips and inside on my gums. Some of the sores were open and bleeding. I consulted with a doctor over the phone who confirmed it was a cold injury. He told me the sores wouldn’t recover while I was in a cold air environment, so basically I had to manage them so they didn’t get worse.

When I woke up first thing in the morning my mouth would often be welded shut in a mass of pus and blood. I’d have to gently use my finger to try and prise my lips open and it was so painful. Eating and drinking became unbearable. I’d try and drink my hot chocolate in the morning by pouring it into the back of my mouth and avoiding my lips. Eating porridge was just excruciating. I’d take a couple of Ibuprofen for the pain. But the moment I went out into the cold air it would hit again. Sometimes I’d be skiing along with tears in my eyes.

You wouldn’t think a mouth could be so painful. I had a grazing bag with chocolate nuts, cheese and salami, and little bits and pieces. I started to notice that on some snacking breaks I had no issues. On others the pain would go through the roof. It took me two or three days of trial and error to work out that it was the Rowntree’s Fruit Pastilles that were causing the pain. I guess there was some acidic content from the fruit. It’s not a great advert, but it’s not their fault!

IV

Neck

The neck’s a big vascular area – there’s a lot of blood flow through there. If you have that exposed all the time it cools your whole body down, because the blood becomes super-chilled before it goes to other parts of the body. So I used to wear a neck buff pretty much all the time. I’ve seen other people get both frostnip and bad sunburn.

‘When I woke up first thing in the morning my mouth would often be welded shut in a mass of pus and blood.’

Louis Rudd

V

Stomach

I had to eat a steady flow of 6,000 calories per day, from breakfast time through to the evening meal. At the beginning, it was difficult to stomach that – towards the end I could’ve doubled it. I lost 15kg, which was 17% of my body mass. The doctor who saw me estimated I was burning 10,000 calories a day but I was eating six. People would say why don’t you carry more food, but then it’s more weight. For breakfast I would have a set 1,000 calorie portion of porridge. In the first ten days it was an effort to eat even half of it. My stomach would be stretched and bloated, but I knew I had to force it down, though it made me dry-retch. By the middle phase of the expedition I could finish it comfortably and feel full, and then in the final phase of the expedition I could have eaten two of them. So I learnt a lot about my stomach on this journey. I’ll be smarter next time and start on fewer calories at the beginning and work up to more like 8,000 calories at the end.

VI

Bowels

The poo blog was my most popular blog apparently. People are always fascinated by how you go to the toilet. My advice is that it’s best to get it out of the way before you set out for the day. Because to go during the day is a pain. The issue is you’ve got to get your layers off. You get super cold because you have to stop for longer. You’ve got to take your skis off, you’ve got to then get your trousers down, you’ve got to get to the pulk and get a shovel out, dig a hole. It’s minus 30 and the wind is blowing, and you just get so cold by the end of the process – it takes you an hour to recover. So I’d go first thing in the morning while my tent was still up. I’d dash outside just in my thermals, take the shovel, use the tent as a bit of a wind-break, and dig my hole. I didn’t actually use toilet paper. It was partly a question of weight, partly about preserving the environment. So basically when I dug a hole, I’d use the chunks of snow that came out and shape them like pebbles to clean myself. And actually it cleans you really well.

VII

Penis

I had a pair of boxer shorts with a little wind-shield on the front. It sounds crazy, but I’ve seen other people suffer with Polar penis – it is actually a thing! It happens when you get a really strong headwind blowing onto that part of your body. It can get quite painful, and people will have to do things like stuffing a woolly hat down the front to make sure it doesn’t get worse. I only wore the one pair of boxer shorts for the 80 days. I got rid of them when I got back to Chile. In 2016 I travelled with Alex Brazier, whose father Julian Brazier, is an MP. He got Polar penis really badly – when he wrote a blog about it, it ended up in The Sun.

VIII

Arms & Legs

You don’t generate much heat in your arms when you’re skiing along – most of it comes from your core. So because you have thin layers, as the blood came down my arms it would get cold – I used to get quite cold elbows. Because the blood was getting super-cooled in my arms, by the time it got to my hands it would be freezing. At first I couldn’t understand why they were cold because I was wearing my big thick mitts. In the end I put some down covering inside my jacket to keep them warmer. My legs, however, were fine, I never had any cold issues.

IX

Feet

I had two sets of skis. When I was skiing across the Antarctic I had to navigate sastrugi, which are wind-formed ridges of ice. The best way of describing it is to say that it’s like skiing across a lemon meringue pie. People think you’re skiing across a flat surface, but you’ve always got some level of sastrugi. The worst incident I had was when I went up a sastrugi ramp without realising because there was a white-out. It was about five to six foot high. I skied off it and face-planted, snapping the tip of my skis. The pulk came over and landed on top of me. I was probably about half way to the Pole by then, so it weighed around 90kg. I lay there thinking ‘This is so dangerous’. I could have broken my back, or my neck. I was very cautious for the rest of the day – though I didn’t stop, I thought I should keep going. That was the worst incident.