Michael Ignatieff’s family has walked the faultlines of history for centuries. His grandfather, Paul, was a Minister of Education in Tsar Nicholas II’s final ill-fated cabinet. One of his father George’s earliest memories was seeing – aged four – the glint of light on the bayonets of the soldiers in February 1917, just before they stormed the Russian Duma.

After the family fled the Russian Revolution, that same four-year-old boy would grow up to become one of Canada’s most distinguished diplomats whose postings included being an ambassador to Yugoslavia and permanent representative to NATO. It was in the former role that he helped rescue more than 5,000 Hungarians from refugee camps along the Yugoslav border, sending them to Canada after the Soviets clamped down on the Hungarian Uprising in 1956.

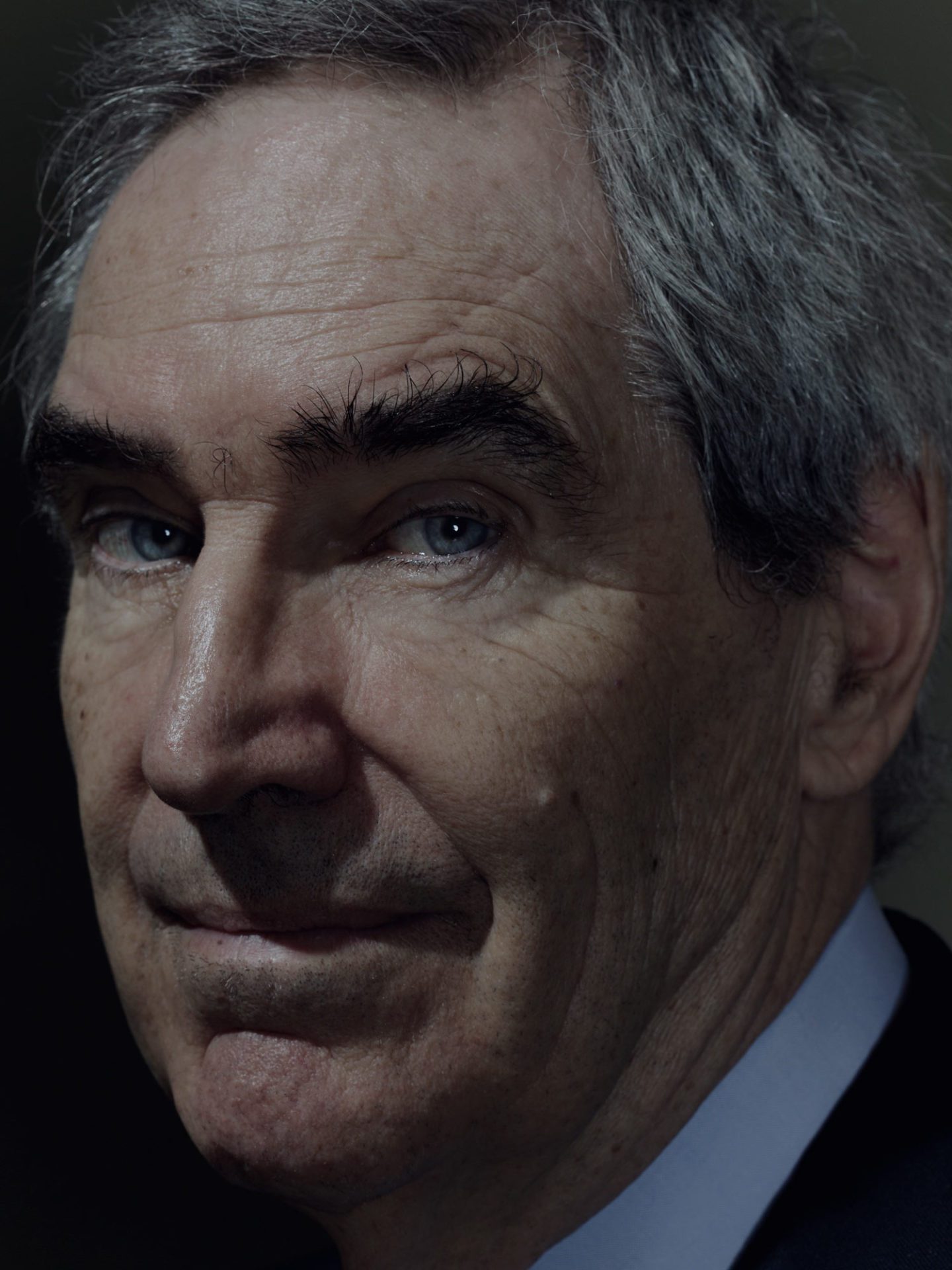

Michael Ignatieff shot by Mattia Balsamini at Central European University, Budapest, 10 April 2019.

Sitting more than half a century later in a Budapest study painted in bright February sunlight, Michael Ignatieff recollects one of the more unexpected outcomes of his father’s diplomatic coup. He himself was born in 1947, and I have asked him what impressions he gained as a child from those early dealings with Hungary. ‘What I remember as a child,’ he replies, ‘is that Tito was so grateful to my father that he made his ocean-going tug [the Galeb – a former mine-laying ship converted into a yacht] available to us for a family holiday. We went from Dubrovnik to Rijeka up the Adriatic coast on a trip that felt like forever, but was probably only ten days. I still have the most vivid memories of night-fishing with the sailors and visiting these beautiful Venetian towns before mass tourism hit the Adriatic. This was all thanks to Marshal Tito, who – let us be clear, was also a dictator and a tyrant – I don’t want to smooth anything over here.’

‘One of the reasons this “rootless cosmopolitan” accusation is so repugnant to me is that whatever George Soros is, he’s Hungarian to the tips of his fingers.’

Michael Ignatieff

Ignatieff, who has spent a lifetime ably deploying words as weapons, is also well aware of how they can blow up in your face. There was a time in the late Eighties and Nineties when his shock of dark hair and Harvard-educated patter made the academic, newspaper columnist and broadcaster very much the thinking person’s crumpet, not least for that smattering of imperial Russian caviar. When I’m working my way through his dizzyingly diverse oeuvre – which includes a Bruce Chatwinesque reflection on his family history (The Russian Album), his Booker-shortlisted novel about Alzheimer’s (Scar Tissue), and his simultaneously loving and deftly analytical biography of liberal philosopher Isaiah Berlin (Isaiah Berlin: A Life) – the impression is of the kind of intellect that could only be won through some Faustian bargain.

Yet he had a major wake-up-call when he became leader of Canada’s Liberal Party, which was then in opposition, from 2008 to 2011, only to find himself eviscerated by a rhetorical Blitzkrieg from Conservative Prime Minister Stephen Harper that framed the cosmopolitan Ignatieff as an opportunist outsider. His record of supporting the Iraq war didn’t help either. In Ignatieff’s memoir on the whole salutary experience, Fire and Ashes, he wrote, ‘I had the disoriented feeling of having been taken over by a doppelgänger, a strange new persona I could barely recognise when I looked at myself in the mirror’. A journalist who interviewed him at the time described him less kindly as being ‘like a jazz man who’s lost his rhythm’.

‘I had the disoriented feeling of having been taken over by a doppelgänger, a strange new persona I could barely recognise when I looked at myself in the mirror.’

After his turbulent expedition into Canadian politics, Ignatieff returned to the less gladiatorial realm of academia, first at the University of Toronto, and then at the Harvard Kennedy School, where he had been prior to the whole experience. Now, however, he finds his life rocked once more by political tremors, this time in Hungary, the same country where his father distinguished himself as a diplomatic hero. As I take the metro into central Budapest from the airport, prime minister Viktor Orbán’s posters – accusing billionaire philanthropist George Soros, along with EU Commission President president Jean-Claude Juncker, of promoting illegal immigration – mark the line like sentinels. The Hungarian Soros, who has given away more than $32 billion to promote democracy and free society, has been particularly targeted for being founder of the Budapest-based Central European University (CEU) – the institution where Ignatieff has been President and Rector since 2016.

One of Orbán’s most toxic tropes is that of Soros as the ‘rootless cosmopolitan’, a nineteenth-century phrase that took on its full anti-Semitic force in Stalin’s Russia to denounce intellectuals perceived as dangerously disloyal to the regime. In Nazi-occupied Hungary it became part of a rhetorical backdrop that saw hundreds of thousands of Jews exterminated. ‘One of the reasons this “rootless cosmopolitan” accusation is so repugnant to me,’ declares Ignatieff, his voice rising, ‘is that whatever George Soros is, he’s Hungarian to the tips of his fingers. He’s a Budapest intellectual whose love of ideas has instilled a capacity to see history clearly. His intellectual shaping by [Karl] Popper is also critical to his financial success.’

He continues, ‘I’ve always felt that the crucible of his life was the summer of 1944 [when, following the Nazi invasion, Soros’s father, Tivadar, used his ingenuity to help his own family and many other Hungarian Jews escape persecution]. I think that experience gave him a chilling historical lucidity that is impressive.’

Ignatieff is at pains, however, to point out that while he finds Orbán’s attacks abhorrent, they have not driven him to become Soros’s puppet. It’s a take that’s hardly surprising from a man who’s always been more comfortable in the role of challenger than that of disciple. In 1994 he infamously asked Eric Hobsbawm on The Late Show whether the death of millions in the USSR would have been justified had the communist utopia been realised (to general shock Hobsbawm responded in the affirmative). In his Isaiah Berlin biography, Ignatieff was happy to take an academic who was greatly his senior to task for the fact that in the philosopher’s book on Karl Marx he ‘never mastered Marx’s economic theory in Das Kapital’. As we talk about the different pressures incumbent on Ignatieff today, he declares, ‘it’s important for me to maintain my independence. Soros is the university founder, he endowed the university. But the academic freedom issue is two-sided – I must be free from Mr Orbán, but also from Mr Soros’.

‘I had no illusions about [the Orbán] regime, but I had no idea we would be the subject of direct attack.’

Michael Ignatieff

Even though Ignatieff’s latest role seems a natural fusing of his academic and political ambitions, he confesses he has been surprised by the extent to which he has found himself on the frontline for defending democratic values. Most recently, he – alongside Reporters Without Borders – won the Dan David Prize for the skill with which he has tackled the vicious government campaign that has forced the CEU to relocate the bulk of its operations from Budapest to Vienna. ‘Frankly I had no illusions about this regime, but I had no idea we would be the subject of direct attack,’ he asserts. ‘The declaration of war came just before Christmas 2016 when Orbán gave a speech to his party faithful when he made it clear that in 2017/2018 the campaign would be to drive George Soros and his projects out of Hungary.’

The current volatility of European politics means that uncertainty continues to prevail on both sides. The CEU has already announced its new six-storey campus in Vienna’s 10th district. Yet not long after we talk, Ignatieff receives an unexpected boost when Orbán’s Fidesz party is suspended from the European Parliament’s largest group, the European People’s Party, in part because of its treatment of the CEU. Ignatieff won’t comment on this directly when I contact him but tells me how moved he has been from the start by support within Hungary for the CEU’s position. ‘In April 2017, students from other universities came and formed a ring around the CEU buildings to protect us,’ he declares. ‘Then in late April 80,000 people took to the streets of Budapest shouting “Free universities and free society”.’ We couldn’t take any part in that demonstration – which was the largest demonstration here since 1989 – because we’re a university we could have no role in organising it. Yet seeing images like, for instance, all the people coming across the Chain Bridge were particularly moving – we had an amazing sense that we were not alone, that we had support from Hungarian academic life, we had support from the people.’

‘It’s important to maintain my independence. I must be free from Mr Orbán, but also from Mr Soros’.

One of the factors that played a part in Ignatieff taking the job in the first place was his marriage to Hungarian Zsuzsanna Zsohar, though he jokes in his Canadian drawl that ‘Zsuzsanna is not to blame’. The pair caused an outcry when they got together in 1995, since it involved Ignatieff leaving his English wife, Susan Barrowclough, of 18 years. At the time the Evening Standard sneered, ‘The Age of the New Man, it is said, is drawing to a close. Right on cue his patron saint – the don, philosopher and sensitive novelist, Michael Ignatieff – has fallen from his pedestal. After 18 years of happy marriage in Islington, Michael has up and walked out, setting up home with a lovely young BBC press officer, Susannah [sic] Zsohar’.

The tabloid tattle took its traditional detour from reality in its implication that Zsuzsanna was any kind of bimbo. In fact she was a brilliant 48-year-old professional who had worked with Ignatieff on the book accompanying his TV series on ethnic nationalism Blood and Belonging. Almost 25 years after they got together, Ignatieff’s unshowy but frequent references to her indicate the transformative effect she has had on his life. Beyond this, his formerly estranged younger brother, Andrew – furious with Ignatieff’s snubbing of him when they were younger – credits her with their reunion, not least for waking Michael up to his humanity. Perhaps one aspect of this was her making a man not unblessed in the self-esteem department able to send himself up. He jokes about his inability to speak Hungarian, saying that at Zsohar’s family gatherings in rural Hungary, ‘I’m the kind of village idiot at the table. They feed me and give me simple tasks’. More seriously he says that visiting Hungary every summer for more than two decades, ‘I’ve watched the [political] climate here darkening every time I came through’.

Both researching Ignatieff in depth and talking to him reveals him as a curious proposition. Now in his early seventies, there’s an easygoing confidence to his demeanour that suggests someone who’s always enjoyed being a lion in the intellectual jungle but doesn’t need to roar about it too much any more. Occasionally he flicks into lecture mode, but more often his resonant Canadian tones are animated either by passion for the ideas he is defending or affection for the friends he is recalling. When he was younger he often attracted epithets of smugness or aloofness. But it seems that life – not least, you suspect, that stint in Canadian politics – has tempered his attitude.

Yet what’s curious is that the strong sense of self he exudes is in counterpoint to the sheer variety of personae he displays in his writing. There’s no doubting the brilliance of, say, a work like The Russian Album or the dazzling conceptual range offered up in his philosophical book investigating the importance of community, The Needs of Strangers. What’s striking, though, is that each book feels almost as if it has been written by a different individual. Clearly they are all genuinely authored by him, but it’s as if Ignatieff is able almost too effortlessly to synthesise the best aspects of each genre he approaches before producing his own version. Or to use the image his great friend and inspiration Isaiah Berlin made famous, he is the ultimate fox in a situation where, ‘The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing’.

At one point in his biography of Berlin, Ignatieff writes that the philosopher was ‘a fox who longed to be a hedgehog; a solitary thinker who longed for society; a liberal, often torn by the displeasure his middle course earned him from friends on the left and right’. Are these sentiments that he himself recognises? He jokes in response that as someone who’s been a journalist, a politician, a professor, and a university president, he’s a kind of ‘caricature fox’. So what does it all add up to?

‘Democratic freedom is conducted against this eternally vanishing horizon line – there’s no final destination. We’re on the road eternally.’

Michael Ignatieff

‘I guess my whole life has been exploring what democratic freedom means – what it’s like to risk something in order to defend it. The great insight of Berlin’s is that democratic freedom is conducted against this eternally vanishing horizon line – there’s no final destination. We’re on the road eternally.’

Another early influence on Ignatieff was Bruce Chatwin – and it’s clear from Chatwin’s quote on the front of The Russian Album, ‘An exemplary Russian performance’, that it was something of a mutual admiration society. When I mention him, Ignatieff becomes rhapsodic.

‘I loved Bruce,’ he declares. ‘I loved the fact that his writing was so non-English – I don’t know where his models were from, but I felt an immediate connection with his wanderlust, with his impatience, with his,’ he shrugs, ‘going to Patagonia. He was a beautiful guy’.

‘When he died,’ he continues, ‘he was in denial that it was from AIDS – there were stories about him being infected in some bat cave in Bali, and the explanations just got more and more baroque. It was at a point when too many of us around him weren’t appreciating the devastating impact of AIDS – it makes me angry now how slow people like me were to acknowledge that this was happening to our friends. I saw him within a couple of months of his death when he was wasting away – he was carried out to a hillside so he could be in the sunshine, and we lay side by side and whispered to each other. And he said that he was coming to the end and there were some facts he must face up to. I feel sad that ten, or even five, years later there’d have been antiretroviral drugs and he’d probably still be alive. My sorrow is that he was just coming into his own – he had dozens of wonderful things still to write.’

We have talked a little about Ignatieff’s stint in Canadian politics, and he laughs when I ask him how it feels that – after he himself was brought in to be the heir to former Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau – it was in fact Trudeau’s son Justin who succeeded in the role. It’s the early days of the SNC-Lavalin corruption scandal that will prove Trudeau’s greatest challenge to date. When Trudeau was elected Prime Minister, Ignatieff praised him in the FT for setting a new tone ‘[a]fter nine years of partisan rancour in the nation’s politics’, but at the same time warned ‘how quickly hope can curdle into disillusion’. Today he is reluctant to discuss the thunderclouds gathering over Trudeau’s government. Experience has made him too canny, and – as his book Fire and Ashes makes clear – while his own political humiliation was very different, it has left him with no appetite to start commenting on another liberal politician in difficulties.

Ignatieff himself, by contrast, seems to have found both a political milieu and an urban environment which – for all its challenges – is clearly bringing out the best in who he is. At one point in our interview, he makes an off-the-cuff reference to the ‘wonderful Bruegel [the Elder] of St John the Baptist preaching in the forest’ that’s now on view in Budapest’s spectacularly renovated Museum of Fine Arts. When I leave the Central European University, on a whim I take the metro up to Heroes’ Square to go and see the painting.

The Sermon of Saint John the Baptist by Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1566).

Characteristically of a Bruegel it’s the crowd that predominates – a swirling sea of faces listening to St John. The different costumes indicate Flemings, Spaniards, Jews and Turks among their number. I am instantly struck by the fact that of all the works of art Ignatieff could have mentioned, he has unconsciously chosen the image of a man preaching to an internationally diverse crowd during an era of persecution. It’s proof, if you will, of the point he’s made that humanity is eternally on the road in its fight for freedom. Where that road will take Ignatieff remains unpredictable. Yet at this dark and unsettled time, how he continues the journey will be instructive to anyone else grappling for an answer.