It would have amused Vaclav Havel to be featured in a journal that celebrates adventure, almost as much as it would have amused him to be celebrated as a great hero of ’68. Though he was capable of physical bravery – on more than one occasion he skied to precarious mountain locations to evade lazy secret police – his natural habitat was the late-night coffee-house, discussing ideas in a fug of cigarette smoke. Yet Avaunt has chosen Havel to celebrate the spirit of ’68 because this extraordinary self-deprecating man did perhaps more than any other individual to translate its anarchic avant-garde spirit into a political vision that became reality.

He was the dissident who became president of Czechoslovakia; a devotee of rock’n’roll and philosophy who used his artistic insights to launch devastating attacks on the communist establishment; a bohemian bon viveur whose moral courage helped change a political landscape.

If you had met him in Prague in the late Fifties, you would have found yourself looking at a young man sporting a quiff, winklepickers (known in Czechoslovakia as ‘Hungarians’), striped socks and a low-cut jacket. As a teenager he got high on Aquinas, Kant and Hegel, earning his spurs as a rebel intellectual in the grand art deco Café Slavia, which he would later describe as ‘my literary kindergarten’. The cool was far from effortless – from his childhood he was both diffident and physically awkward, and even when I met him in 2009, long after he had become internationally renowned, he protested that ‘I’m a shy person’. But a thirst for thought meant he had no fear in seeking out and befriending leading thinkers of the Czech nightlife scene, while his aspirations to write meant that he had a heightened awareness of writers who were being persecuted. In 1956 he began to mark himself out as a political figure when he spoke out publicly about their unfair treatment at the hands of the Communist regime.

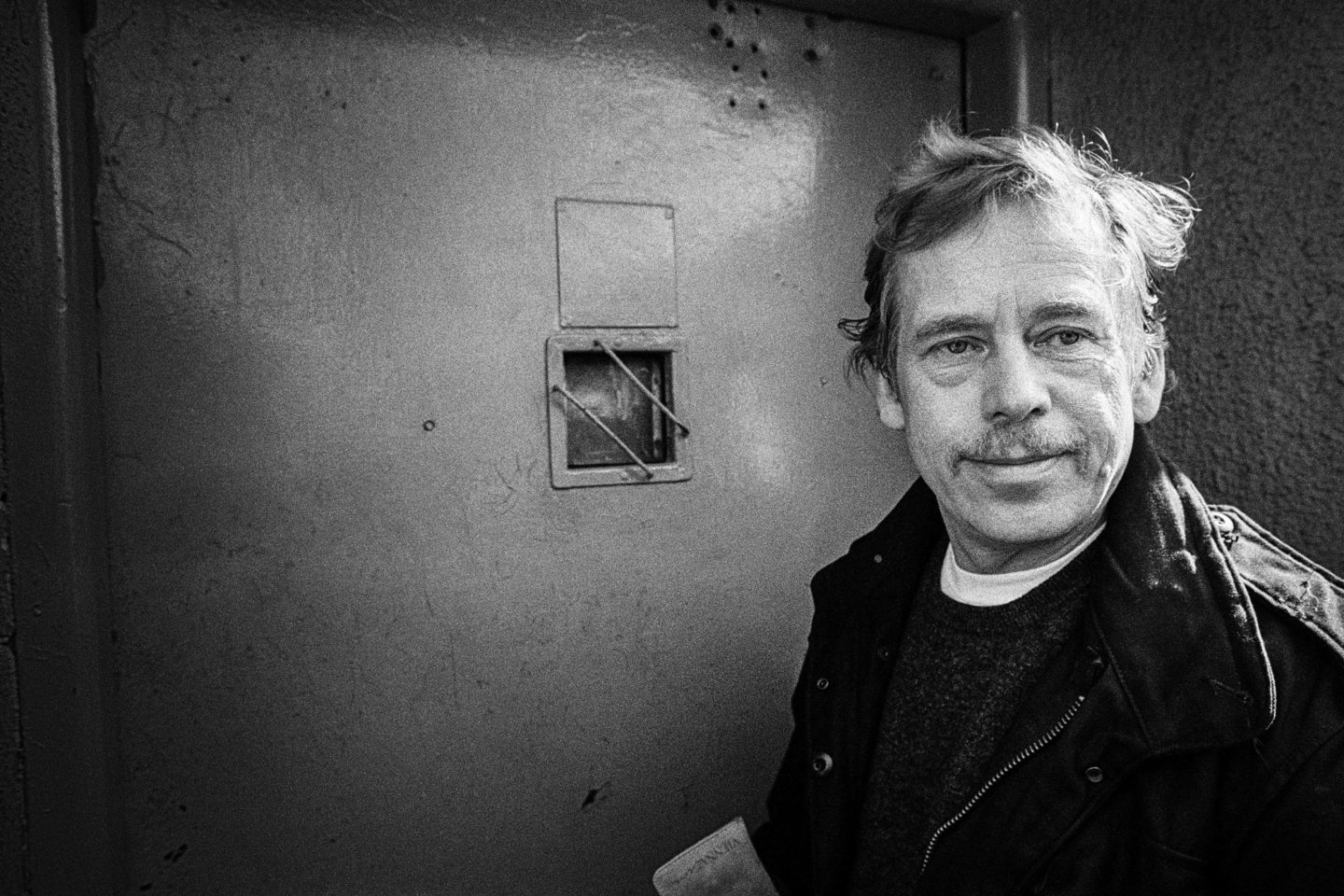

An unplanned stop at Ruzyni Prison, where Vaclav Havel had been imprisoned. Prague, 17 March 1990. Photography: Tomki Němec.

His own difficulties had begun at the age of fourteen, when he was branded a ‘bourgeois element’, and was forced to leave school, so he could ‘redeem’ himself through manual labour and taking on the values of the working class. Did this accident of fate end up pushing him to greater heights than he would ever have attained? Even if you were to debate this for several hours, perhaps smoking cigarettes and drinking Becherovka, the straightforward answer is that there is no straightforward answer. Havel’s difficulties may have led to his being president, but he came from a wealthy family whose members had demonstrated themselves to be natural pioneers for decades.

His grandfather was a construction and property magnate whose developments included Lucerna Palace – the city’s first multipurpose shopping and entertainment complex – celebrities who performed there later in the century would include Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong. His father and uncle also went into property, but they – like Havel himself – found their vision changed after visiting America. In love with California, his father radically reinvented Prague’s architectural style, interrupting the chocolate-box pretty Baroque and Rococo landscape with the first flat-roof functionalist villa as part of an exclusive property development. His uncle’s passion for the West Coast led him to build the Hollywood-inspired Barrandov film studios, which would become one of the largest filmmaking facilities on the continent.

Havel at the first public concert of the singer Marta Kubisova after her 20-year performance ban. Prague, 1 June 1990. Photography: Tomki Němec.

Havel himself – nicknamed the Dung Beetle at school – was famously embarrassed by his privilege, and once, when asked to tell the class what his father did, muttered that he ran a couple of bars. But when the Communist putsch of 1948 turned this privilege into a crime, his life was turned upside down, and he was made to earn his living as a chemical laboratory assistant at the Prague School of Chemical Technology. He continued his education at evening classes. An early desire to become a scientist was supplanted by the ambition to express his political and personal thoughts as a poet. He also wanted to work in film, but his attempts to get into film school were repeatedly thwarted by the communists, so after a stint in the army, he decided his rebellion would best be expressed through playwriting.

Today political activists seeking to change their world use social media to sow rebellion, or, if they use live art forms, they’re most likely to turn to street trends like graffiti or hip hop. But in Fifties and Sixties Prague, when the internet was decades away, and rock music was a new form frowned on by the authorities, theatre was the public forum where the radical artists of the day chose to express themselves. For Havel it was a place of intellectual experimentalism that fused with the burgeoning jazz and rock’n’roll scene: an early rock band The Akord, managed to escape communist censorship by introducing sketches between songs, and calling it theatre. An underground ‘small theatre movement’ (including Theatre on the Balustrade and Semafor Theatre) sprang up – later Havel would describe theatre as nothing less than ‘a seismograph of the times, a space, an area of freedom, an instrument of human liberation.’

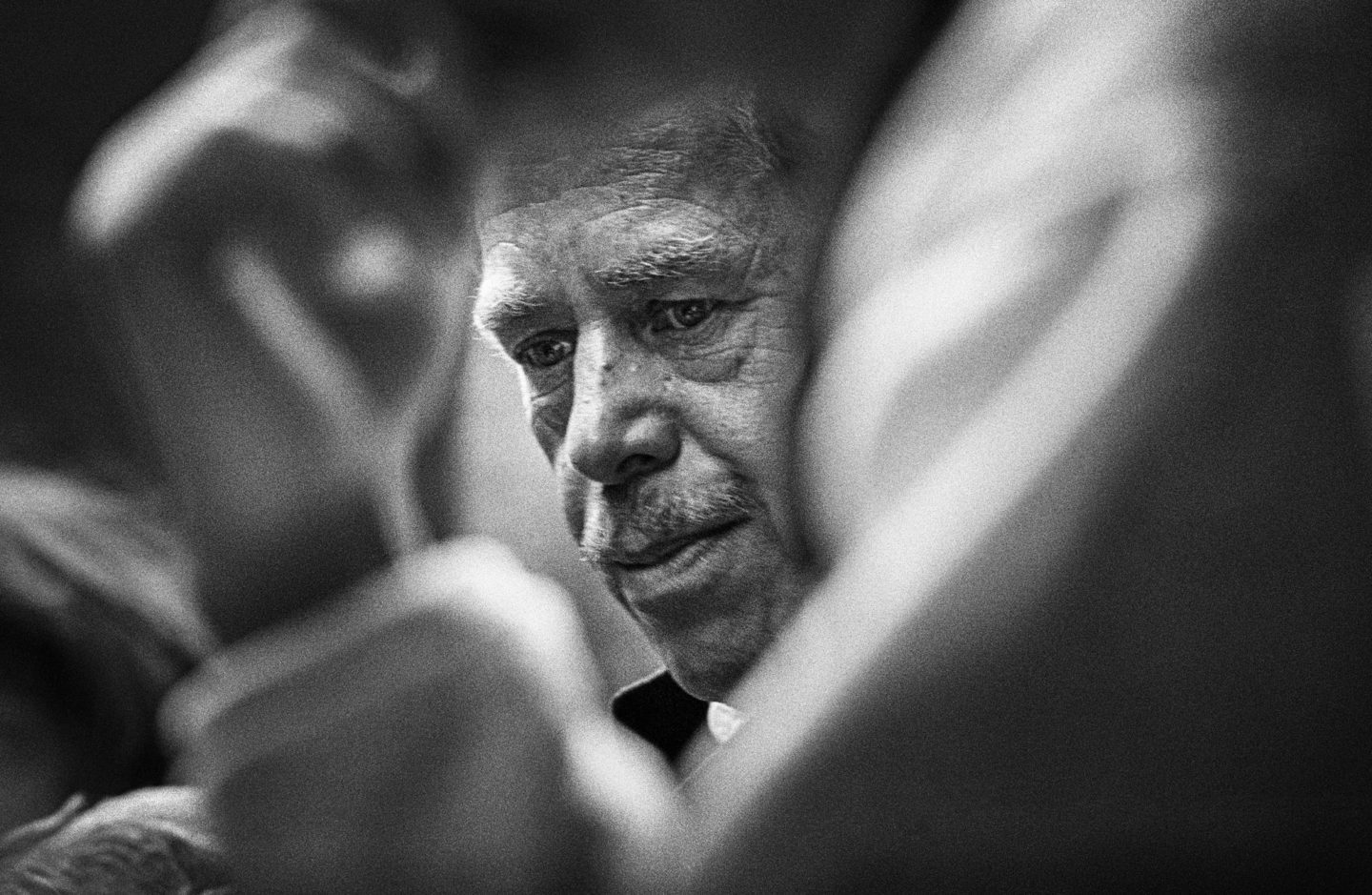

In front of the Federal Assembly, Czechoslovaks demand that deputies elect Vaclav Havel President. Prague, 19 December 1989. Photography: Tomki Němec.

In 1963, he wrote The Garden Party, an excoriating comedy in which a young middle-class man, Hugo Pludek, is encouraged to advance himself by going to meet the powerful Mr Kalabis at a garden party held by the Liquidation Office. In a Kafkaesque twist, he never finds Kalabis, but after a surreal series of encounters with functionaries who spout meaningless ideological cant, he himself becomes like them and ends up as head of the Central Inauguration and Liquidation Committee. This satire on people who sold out by advancing their interests through the Communist regime made him first nationally, and then internationally famous, and was followed in 1965 by The Memorandum. Daringly it focused on a language Havel and his brother had devised using artificial intelligence, ‘Ptydepe’, which is introduced into an organisation to promote efficiency, but alienates and humiliates everyone using it, not least those who think they are in control.

A little over forty years later, Havel would tell me his theatre background had helped him when he himself became a politician, ‘because it allowed me to step back and see everything from a distance. It always enabled me to send myself up and see the absurdity in situations, which may not always have been 100% helpful, but it gave me some immunity.’ It was a classically self-deprecating statement that similarly revealed how great the revolution had been in his country’s politics. Havel’s brilliant insight under communism was to see that the regime was so brittle with contradictions, that pointing out its absurdities – far from providing light relief – would prove a potent weapon. For authoritarians who would tolerate no opposition, such insights were highly threatening, since they would go on to reveal – as he later wrote in his iconic essay ‘The Power of the Powerless’ that ‘the emperor had no clothes.’

Photography: Tomki Němec.

I talk to Michael Zantovsky, the Czech fellow-dissident who became publicly associated with Havel when he carried his bags after the playwright was released from jail for the last time in 1989. Later Zantovsky would become his press officer, and ultimately his biographer. ‘The language of politics, and its uses and abuses was one of his strong themes – he wrote about it seriously in essays, but it was particularly effective because he demonstrated it in a way that was often hilarious in his plays,’ he says. ‘Because of their success, he was able to convey his message on a massive scale in the period running up to 1968.’

Photos from the 1960s reveal Havel with collar-length hair (the quiff long gone), his trademark moustache, and a cigarette between his fingers as an almost permanent fixture. In 1968 it seemed that he had been one of the chief heralds of the new era when the reforming leader Alexander Dubcek was elected as First Secretary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, ushering in a wave of measures that released constraints on speech, media and travel. But though Havel had fought for such changes for years, he was characteristically wary. As Zantovsky eloquently puts it in his biography, ‘His artistic sensitivity responded to the psychedelic kaleidoscope of music, costumes and ideas that defined 1968, but his gentle and orderly nature revolted against the chaos and violence that accompanied it [worldwide]. Politically and philosophically, Havel was made in the Sixties more than by the Sixties. His principal themes of identity, truth and responsibility had already been formed.’

‘He was an incredible networker and a bit of a schemer in the better sense of that word. And a necessarily effective unifier.’

Michael Zantovsky

Yet Havel’s passion for pop culture and the psychedelic would inform his style when he became president in 1989, just as much as his philosophical passion for truth and responsibility. Which other president would have made Frank Zappa ‘Special Ambassador to the West on Trade, Culture and Tourism’? Or made a defining moment of his early presidency a rock concert by the Rolling Stones, ‘I was happy that I had the chance to meet musicians who from our perspective had been like God,’ he told me. In 1968 itself, he took a trip to the US to see ‘The Memorandum’ produced in New York – a prized souvenir was a Velvet Underground album. Former US President Bill Clinton recalled in an interview given last year that, ‘When I invited him for dinner at the White House [in 1998], I said ‘What do you want [for entertainment]?’ He said, ‘I want Lou Reed – he helped the Velvet Revolution.’ So we got Lou Reed. Lou Reed virtually came out of retirement and performed for him!’

Yet in the late summer of 1968, such a flamboyant liberal agenda suddenly became a remote possibility again. On August 20, Soviet tanks rolled into Czechoslovakia, ushering in harsher communist rule. Havel and his wife Olga were staying in Liberec with friends when this happened, and so were not among the crowds who protested in Prague. However, Havel’s swift response demonstrated all the characteristics that would go on to make him a leader.

Joining the resistance as a radio broadcaster, he released a series of broadcasts condemning the immorality of the invasion. ‘Let intelligence triumph over brutality, humanity over bestiality, solidarity over military orders, the discipline of conscience over the discipline of guns,’ he declared on August 23rd. Just as crucially he sent out an appeal to the international network he had started to build as a playwright. ‘I appeal to Gunther Grass, Hans Magnus Enzensberger, Helmut Heissenbuttel, Kenneth Tynan, Kingsley Amis, John Osborne, Arnold Wesker, Friedrich Durrenmatt, Max Frisch, and the leading French writers Jean Paul Sartre, Louis Aragon, Michel Butor, to the International PEN Club led by Arthur Miller, to Samuel Beckett, Eugene Ionesco, Yevgeny Yevtushenko, Andrei Voznesensky, and to all of our writer colleagues, to add their voices, in this extremely difficult moment, to those who condemn the aggression of the Warsaw Pact countries against Czechoslovakia.’

When I put it to Zantovsky that it was Havel’s talent as a networker as much as his brilliant insights as a political philosopher that marked him out from other activists, he concurs. ‘That is a hidden side of him that rarely gets discussed,’ he replies. ‘He was an incredible networker and a bit of a schemer in the better sense of that word. And a necessarily effective unifier. And that might be something unique in him.’ Asked if he thinks anyone but Havel could have become president when Czechoslovakia finally became a democracy in 1989, he at first says, ‘I can only argue that he fulfilled that role better than most. But I would never say that no-one else could have done it – that would be ahistorical.’ However, he concedes that, ‘I can’t seriously think of anyone else at that time who could have brought together so many disparate groups and people, who twenty years before then and twenty years later don’t even speak to each other. But he did it, and he deserves enormous credit for that.’

The President talking to people assembled on the Third Courtyard of Prague Castle, shortly before his inauguration as Czech President. 2 February 1993. Photography: Tomki Němec.

It would take twenty-one years till that next breakthrough, and for some Czechs at the time it must have seemed as if it would never happen. The playwright Tom Stoppard – whose hugely successful play Rock’n’Roll would later provide one of the great accounts of the connection between rock culture and the Velvet Revolution – had a close friendship with Havel built on mutual professional admiration. He tells me, ‘Many people have half forgotten that ’68 was followed by a regime that was much more aggressive than the one that preceded it.’ Havel himself became increasingly subject to interrogations by the secret police. Like many fellow dissidents, he spent a lot of time in the countryside – in his case, in the house he and Olga shared in Hradecek. Thwarted by the real world, many dissidents started to create parallel fantasy worlds through societies like ‘A Club of Balloon Flight’, or ‘The Fatherland’s Palette’, a club for artists, filmmakers and athletes. The latter society ran an annual car rally, which according to Zantovsky ‘in 1971 counted among its drivers a Mexican-looking gentleman in a big black Mercedes car who was none other than Vaclav Havel.’

Which other president would have made Frank Zappa Special Ambassador to the West on Trade, Culture and Tourism?

This departure to the countryside was not so much a retreat as an enforced decision to regroup resources and wait for the next opportunity. In 1975 Havel put his neck on the line when he wrote a letter to the then Czech president, Gustav Husak, analysing the social decay wrought by communism, along with the ‘existential pressure’ of the secret police. He was not arrested then, but in 1976, when the communist regime arrested the Zappa-influenced band ‘Plastic People of the Universe’ and put them on trial for ‘disturbing the peace’, Havel – who knew the band – leapt into action. Furiously he denounced the arrest as an attack by the totalitarian system on human freedom and integrity, the essence of life itself. The following January, he helped create Charter 77, a document that criticised the government for failing to preserve the basic human rights to which it had signed up through a series of international agreements made in Helsinki in 1975. The distribution of the Charter proved almost film-worthy – when Havel and one of his chief partners in crime, the actor Pavel Landovsky, set out to distribute the document to different postboxes the secret police were waiting. According to Landovsky – who was driving a Saab as a ‘getaway’ car – the police were so desperate to catch them, that two of the police collided in their Skodas. A high-speed chase ensued, in which Havel managed to stuff a few of the copies of the charter into a post box, shortly before the Saab was surrounded, and he was dragged out of the car. In no small irony, some passers-by, recognising Landovksy as an actor, stopped to watch, thinking that they genuinely were watching a movie being made.

Havel in Hrádeček, north-east Bohemia, 1996. His wife, Olga Havlová, had just passed away. Photography: Tomki Němec.

On 14 January Havel was sent to jail for the first time. Over the next twelve years, he would become so accustomed to being put behind bars that he would always carry toothpaste, razor blades, and his favourite unfiltered cigarettes in case of arrest. He knew he had the chance to go into exile, but refused – though inevitably he suffered, internationally the imprisonments raised his profile, and in intellectual circles he began to be seen as the equivalent of a Solzhenitsyn. It was during this period that he wrote The Power of the Powerless, the infamous essay that asked the reader to imagine a greengrocer putting the sign ‘Workers of the World Unite’ in his shop window. To read that essay again, and appreciate the brilliance and subtlety of his analysis of how words could be used as a cloak for political oppression, is to mourn how lacking we are in such humane intelligence in politics today.

His last release from prison before he was catapulted into the presidency was in May 1989. International pressure helped bring about the release, but even then there was no sense that he would go on to lead his country. Two years beforehand, when Gorbachev had made his first visit to Prague, Havel had joined the cheering crowds, and later confessed that he felt pity for those pinning their hopes again on an external power who was bound to disappoint them. ‘He was just somebody standing around in the street,’ says Stoppard. ‘It’s extraordinary to think back on it – he was intrigued by what was going on, but very much part of the crowd.’

Havel bows out as President at the National Theatre. Twenty-six years earlier, a communist-controlled event here – the so-called anticharterʼ – declared Havel and his colleagues from Charta 77 to be outlaws, sending them to prison. Prague, January 2003. Photography: Tomki Němec.

‘If you think about it, there have been three people who essentially liberated their country without firing a shot: Gandhi, Mandela, and Havel.’

Bill Clinton

Yet throughout the year there were tremors – protests and petitions that indicated that dissidents were gaining confidence once more. Tensions rose on 9 November when the Berlin Wall fell – then on 17 November people gathered in Prague for a peaceful protest to commemorate students arrested and killed by the Nazis. An over-aggressive response by the secret police only encouraged the demonstrations to escalate – and Havel, who had been anticipating such unrest, rushed to Prague to meet fellow dissidents. Within days the Civic Forum had been created, with Havel’s philosophical clout, international renown, and talent for co-ordination revealing him as the natural leader. On 10 December he was announced as the new president of Czechoslovakia.

Like other revolutionaries who have gone on to govern their countries, he himself would eventually be subject to criticism for hypocrisy and failing to live up to his values. I was in Czechoslovakia when it voted to split into two countries, and remember the feeling of disillusionment when he announced his resignation on TV – though he would be re-elected as president of the Czech Republic on January 26 1993. His never less than colourful love-life also provoked problems when he married the young actress Dagmar Veskrnova a year after his first wife Olga died, though Stoppard argues that ‘she saved his life without question. When he was very very ill [with lung cancer] it was her force of personality that got him the right treatment.’

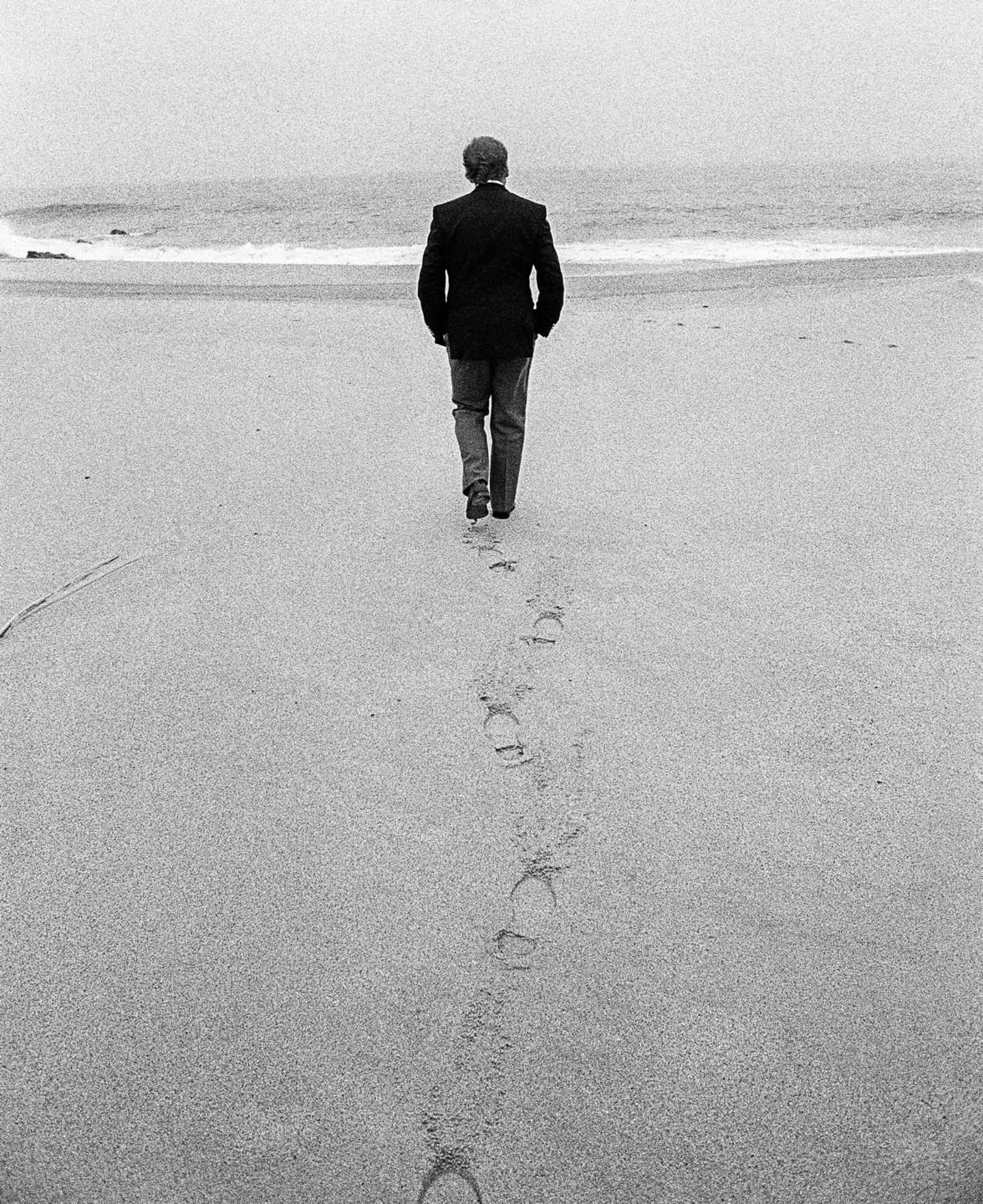

Vaclav Havel walking on the beach near Cabo da Roca, Portugal, 1990. Photography: Tomki Němec.

Seven years after his death, however, it remains equally clear that overall the self-confessedly flawed Havel left an impressive legacy. The fight against communism made him a great internationalist – because of him the Czech Republic joined both NATO and the European Union, and there is no doubt that he would have fought against the nationalism spreading across Europe again now. In a world where the onslaught on liberalism has become unremitting, the eloquent essayist who arguably became the only true rock’n’roll political leader remains an enduring reminder of the most positive aspects of ’68. As Bill Clinton says, ‘The life that he lived that brought him to the presidency is more relevant [than ever] today… If you think about it, there have been three people…who essentially liberated their country without firing a shot: Gandhi, Mandela, and Havel.’

Tomki Němec was President Václav Havel’s personal photographer – the youngest personal photographer of a head of state in the world. He has received two World Press Photo awards.