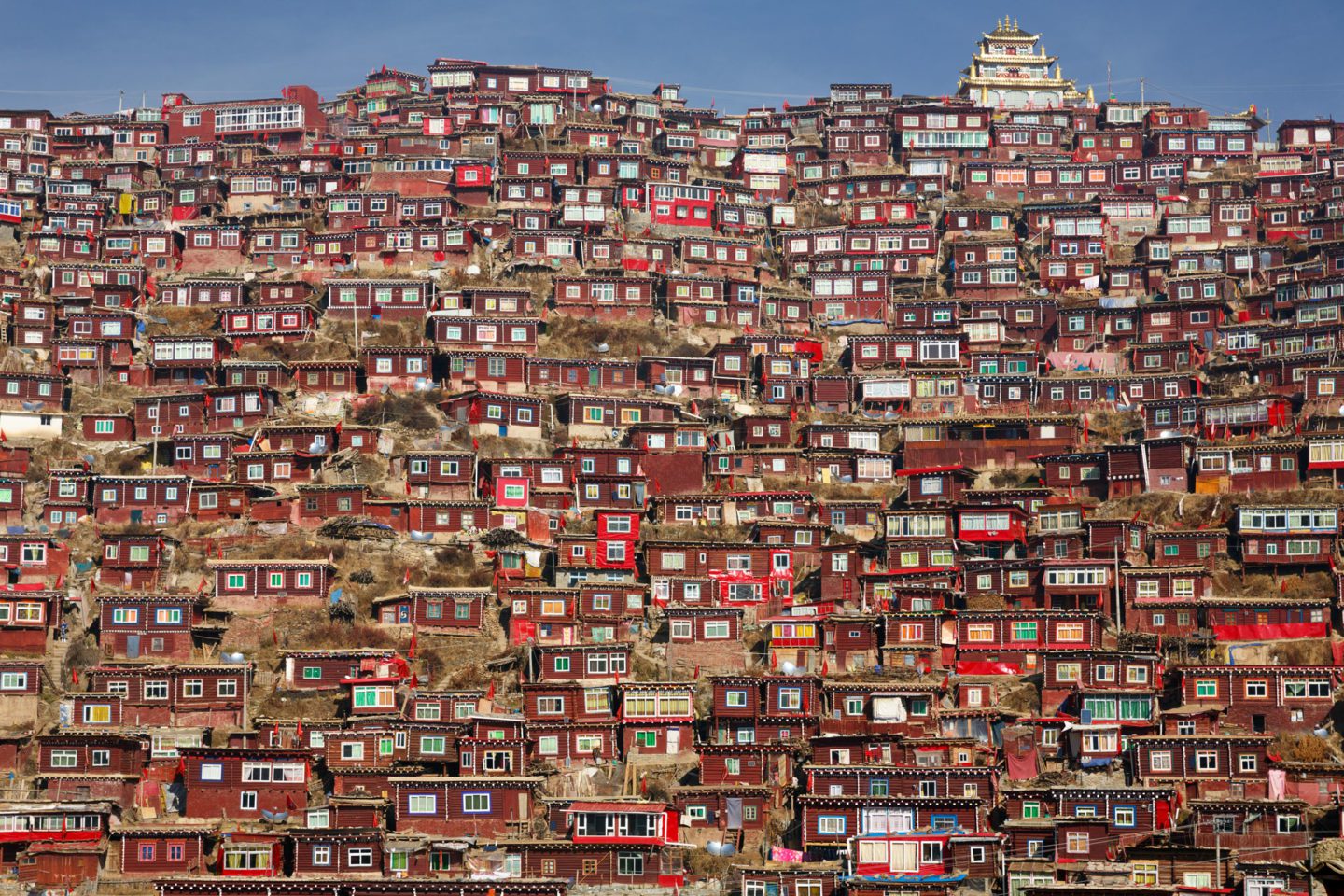

When Colin Miller took these extraordinary pictures, he didn’t realise that the institution he was photographing would shortly be fighting for its very survival. Larung Gar – also known as Seda Monastery – was one of the largest religious institutes in the world, its population ranging from 10,000 monks and nuns to 40,000 during festivals. Perched on the edge of the Tibetan plateau at an elevation of 3,962m, it was known as the ‘city in the sky’. But in 2016, against the backdrop of a wider religious crackdown, the Chinese government decided to impose controls declaring that the population had to be reduced to 5,000 by the end of the following year.

The homes of the monks at Larung Gar seem impossibly stacked along each face of the valley. Tiny paths wind through the wooden structures. Fire is always a major concern here; once a fire starts it is nearly impossible to stop.

Miller’s own journey was a year before the order was issued. ‘I took a bus for 36 hours from Chengdu,’ he says. ‘The roads were treacherous – especially when you had giant tractor-trailers roaring down in the opposite direction. I arrived in the afternoon to discover there was a festival on. I woke at 6am the next day before sunrise, and heard the sound of monks chanting. I went to the courtyard and there were thousands of them – it was one of the most incredible things I’ve ever seen.’

Six nuns talk on a small overlook next to one of the homes. Everything is red here, even most peoples’ shoes.

There are sky burials close to Larung Gar, in which the bodies of the dead are exposed after three days of ritual and prayer. ‘Giant vultures are constantly circling the hill, waiting for the bodies,’ Miller says. ‘Often people have to make the bodies smaller for the birds by hacking them up with machetes. You have a much greater sense of death everywhere than you do in the West.’

Each day thousands gather outside one of the temples for hours of droning chants. Monks and nuns huddle in the cold as chanting echoes through the valley, creating a comforting blanket of sounds.

Against the backdrop of deep reds of robes and hats, a nun sits silently at the entrance of a temple. Her total serenity was striking.

He tried to return in December 2016, but by that time the Chinese government was shutting it down to foreigners. ‘The government line was that it was a fire-hazard,’ he said. Yet the thinly veiled excuse for religious crackdown has subsequently become transparent. An eight-month demolition programme led to five thousand dwellings being torn down, and a similar number of people evicted. Monks and nuns who have returned to their native regions have been prevented from joining other monasteries and nunneries, as well as being forced to undergo patriotic re-education sessions. Three nuns are reported to have committed suicide.

Vultures squawk and jockey for position in anticipation of a sky burial. When a local Buddhist dies, the body is often brought here, one of the few remaining places where the Chinese government allows the practice to continue.

Smoke from the tents of thousands of pilgrims gently fills the valley with a fragrant mist as the worshippers prepare dinner.

At the start of this year it was announced that the Chinese authorities were taking over the centre, splitting it with a wall and placing atheist Communist Party officials in high-level administrative positions. Miller denounces the act as ‘brazen – even with my dim view of their human rights record, I’m shocked that the Chinese government would take this step. The problem is that it’s so below the international news radar that there’s little chance for reversal.’

And so his images, rather than being a celebration of one of Buddhist culture’s great glories, become a haunting memorial to a vanishing way of life.