“We are not lost,” Devi says. At the bottom of a cliff that rears up so violently all we can see above us are trees, waist-deep in water too cold to breathe in, we scan for the path, slipping on rocks so sharp that Devi’s feet are already pouring blood. “We are not lost…”

Our phone signals vanished hours ago. It’s getting dark. We don’t have a map: Devi had ignored my idea to bring one.

“There is a path,” Devi insists. “I only have to be in a place once – I remember it forever. I know Tusheti better than the Tush do.”

When the horse falls, scrambling, into the river, soaking our tents and sleeping bags, Devi shrugs.

“You are like me,” she lights her 10th cigarette of the day. “How I was in the beginning. Only I had no tent. And I was alone.”

Devi Asmadiredja with her Tush horseman, Vaxo, and gear. Many Tush will not rent packhorses to non-Tush directly.

She starts to tell the story of how she spent 12 days once, not far from here, with a broken ankle and no food or water, but I already know it.

Everybody in Georgia does.

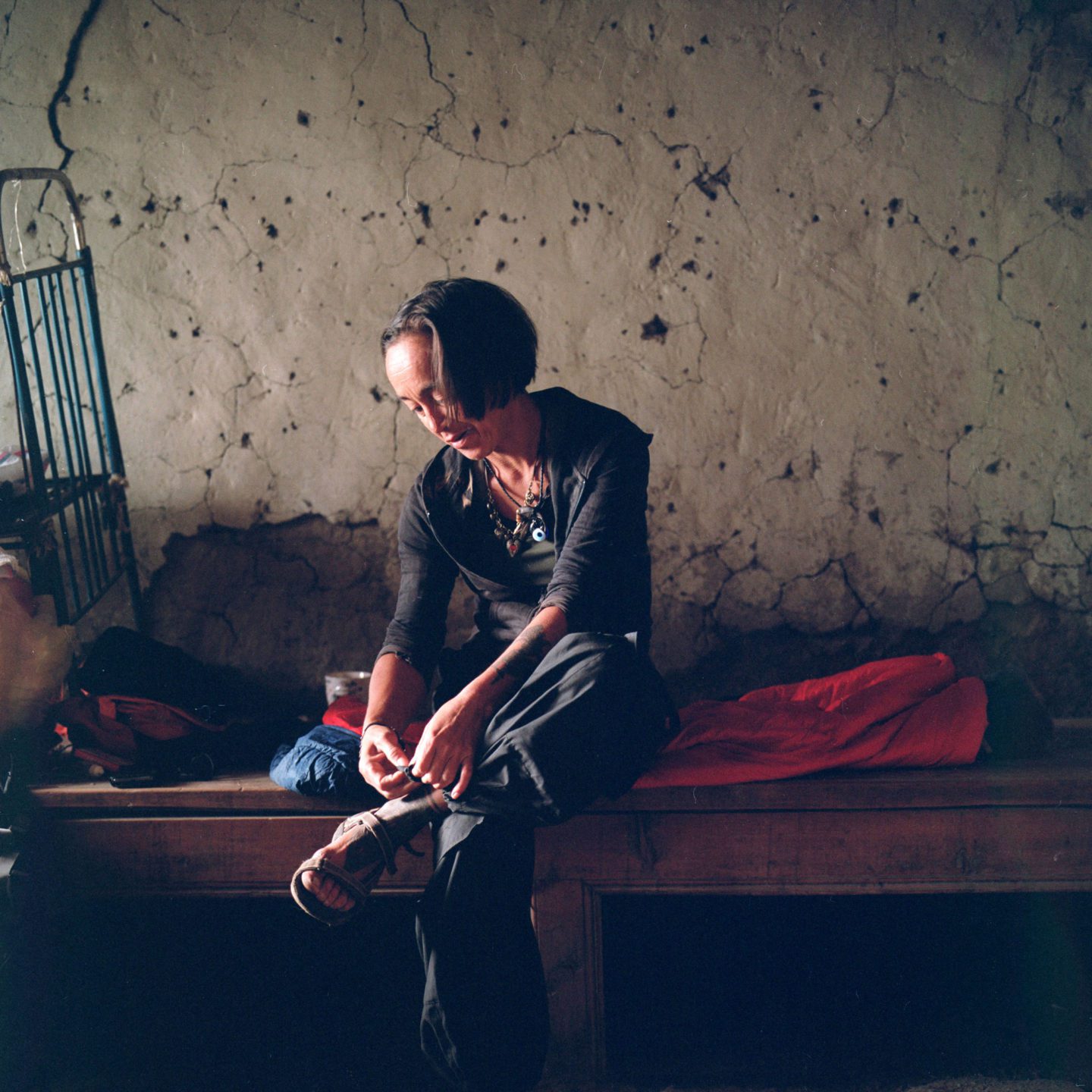

Devi Asmadiredja may be the closest thing the South Caucasus – nestled east of the Black Sea between Russia, Turkey and Iran – has to a modern folk hero. Raised in east Germany by an unmarried mother – who’d separated from her Indonesian father before she was born – Devi spent her 20s in the drug-fuelled nightclubs of post-wall Berlin, before falling into an abusive marriage with a Chechen petty criminal. One day, five years ago, Devi suddenly appeared in Georgia’s Chechen Pankisi Valley, ostensibly to learn enough Chechen to teach it to her husband back home, and set about, at the age of 40, creating for herself something between a life and a legend.

Devi, vocally opposed to photography, is more than willing to pose at the pass above Dedikorta.

I first met Devi in April 2014, while putting together notes for what would become a BBC feature about her transformation into the hermit of the Caucasus. I’d heard all of her stories: how she arrived off the marshrutka bus knowing no Chechen, no Georgian, nobody at all; how her husband called her shortly after her arrival to tell her not to bother coming back; how she was informally adopted by a local Chechen family over the objections of locals convinced she was a Russian spy; how she started taking off for days or weeks at a time, first around Pankisi and then up the mountain pass – into the wilds of Georgia’s Tusheti region, where pagan shrines still dot horse roads; how she slept in shepherds’ huts and in a cellophane-wrapped sleeping bag in the open air and in caves wedged in outcroppings.

It’s the kind of story it’s almost impossible to believe; and yet, listening to Devi idly rattle off her adventures over all those glasses of wine I’d bought her in Tbilisi, Georgia’s capital, I’d found it impossible not to.

These are the mountains the Russian poets loved – Pushkin, Lermontov, Tolstoy. They romanticised their remoteness: Cossacks with their daggers, kindhearted shepherds, the atavistic presence of old gods.

Scrawny and steely-eyed, with all the angular compactness of a pocketknife, Devi answered my questions with acerbic assuredness. No, she’d never been afraid – the only thing that scared her was getting deported back to Germany. No, she never worried about starving – she could live on a handful of nuts a day. No, she’d had no outdoor training – she’d simply woken up one morning, gotten sick of people, and decided to start walking into the mountains.

As a journalist, I’d so often found myself with my nose pressed up against the glass of experience. I’d interviewed Sufi mystics and Turkish shamans, male belly dancers and Armenian street preachers, seeking out those on the margins of experience. I’d intellectualised adventure: my pen kept me at safe remove from the intensity I wrote about.

But Devi, I thought, was the real thing. What I wrote, she lived. I wanted to understand what brought her to the mountains. I wanted to understand if I could do it too.

Arkady Baktoridze, one of the few year-round inhabitants of the village of Iliota, is an old friend of Devi’s.

And so when she suggested, some months later, that I follow her into Tusheti – to the shepherds’ huts, the overgrown forests, the pagan shrines, a six-hour mountain drive so dangerous that the roads are dotted with the graves of those who have fallen over the edge – I did.

Two days later, we are at the foot of another mountain, drenched, at dusk, miles off the path Devi decided to ignore.

“I told you,” Devi says, when I ask her how far the next village is, “I have a photographic memory. I never forget.” She doesn’t answer the question.

I have spent four hours scrambling down a vertical forest whispering under my breath the names of travel writers who have had real adventures, just like these – adventures that thrilled and upended them and transformed them: Dervla Murphy, Jan Morris, Freya Stark. I tell myself that this is what I, too, will be – once we make it to safety. By the fifth hour, I start to wonder if we ever will.

“You will not die,” says Devi. She sounds less sure than she did.

View from the home of Sograt Bakunadze – our overnight saviour – in the village of Gogrulta.

Devi has attached her sandals to my backpack and is walking barefoot through the river, keeping me aloft as we both balance on her wooden staff. We climb under hunchbacked branches, over swollen encroachments of earth. The light is falling. More than once we walk straight through patches of stinging nettles and ignore the pain, because we cannot take the time to think.

The sun has gone by the time we find the path, snaking up a mountainside as high as the one we’ve just descended. A wrong move could send us over the edge.

Our tents are drenched. My shoes are soaked. Temperatures in Tusheti in September drop to zero at night.

We keep on walking.

There is exhaustion, and then there is the pain that comes after: a dark, inward sweat so pervasive that the only thing keeping me putting one foot in front of the other is the impossibility of not doing it.

I ask Devi how much longer.

She looks as panicked as I feel.

It is pitch-black by the time we see the light across the gorge.

When we at last fling ourselves across the threshold of the slanted stone house in Gogrulta Village, the seven old men in fatigues and leather jackets – drunk on chacha, noxious Georgian moonshine – welcome us. They bring us to the fire. They bring us mountain food to warm us: mushrooms stewed with tarragon, melted cheese. An elderly cowherd, Sograt Bakunadze (the name of an “old Georgian king”, he says, though there is no ‘Sograt’ in the historical record), brings us to his house; he bangs on the doorframe until his wife wakes up to serve us.

He offers us homemade wine to restore blood to our toes.

“I’ve drunk five litres already,” he crows.

We dry our sleeping bags by the fire and sleep on spare beds, under a wall of stringed lyre-like pandauris. Mice scurry under our beds. Across the gorge we can see lightning, silent and bright, flickering over Dagestan.

Cows and sheep are common sights in Tusheti, and many villages are inhabited only by seasonal herders.

Devi first came to Tusheti in search of solitude. But the Tush know that in the mountains, self-reliance is a death wish. Codes of hospitality keep us warm, fed, alive.

When the Tush return to the lowlands for the winter – the mountain pass is inaccessible six months of the year – they leave their doors unlocked. The few travellers – cowherds, shepherds, Caucasians from over the border – who pass through these dusty stone villages, are welcome to seek shelter, to take what they need and leave what they can behind. The stones of Sograt’s walls are chalked with the legacy of so many travellers: Ia, 1979, Nino 1986, Dato, 1994.

At breakfast, Sograt drinks Czech liquor from a bottle; Lili – like any good Georgian woman – serves us pickled greens, fresh cheese, Tush thyme tea. Here in the mountains, women have their place. They’re barred from the kharebi: sacred horn-crowned shrines. In each village we pass, we hear the same story: a woman, eavesdropping on war deliberations at this holy spot, once gave away strategic information to an enemy clan. When the men gather annually in summer for Treoba – the date varies from village to village – women must keep away as they bring out the sacred icons, locked away by each village’s patriarch, and brew the sacred beer all will consume at the supra, or feast.

Not Devi.

Lili, Sograt Bakunadze’s wife, stirs up a breakfast of cheesy grits over the fire in Gogrulta.

She turns down Turkish-style coffee, demanding Nescafé – a pricey delicacy here – instead. She does not help serve. She bandages the blisters on her feet and asks Sograt about the cows’ latest yield in meticulous, German-accented Georgian.

“Three years ago,” she tells me, as we set off above Goglaurta – our horses loaded up by a pre-adolescent cowherd who insists he’s heading back to school “soon” – past a slanting field of trees gravity has pulled downward into tired, contorted shapes, “a shepherd tried to rape me – near that hut, there.” This story, too, is one I’ve heard. “But I have my knife.” She fought him off, she says, and soon the Tush men learned that Devi was not for their taking.

“You know what they say about me? I am their brother.”

Still, she’s had romance: the farmer who found her camping in a cave and insisted upon bringing her hot khinkali dumplings from his mother’s house each day; the much-younger Tush shepherd for whom she left him; the Indian man who, upon reading her BBC profile, sent her 34 love poems.

Morning in the village of Chiglaurta. The pagan stone shrine, bottom right, may not be approached by women.

But even now, Devi says, for the fourth or fifth time that day: “People cause trouble. I am better when I am on my own.”

It’s a refrain Devi repeats every time we pass a village, every time we stop and a shepherd offers us shelter, every time we accept it. In Iliota, white-haired Arkady Baktoridze – who helped nurse Devi back to health with chacha after the attempted rape – insists we let his wife serve us jinjoli greens and fresh bread. In a valley near Chesho, Tusheti’s oldest shepherd – the 85-year-old Pora Telidze – stops doing his faded crossword puzzle in a shack, the beams of which are thick with wool, to embrace Devi and introduce her to his sad-eyed preteen nephew as “your aunt”, before serving up bowls of sheep fat to spread on toast.

I do not think I have ever been less solitary.

And still Devi keeps the myth alive.

“They’ll all want to know about me,” she grins, every time I ask her a question. “Who is that crazy woman, running up the mountains, alone?”

Devi descends a mountain pass just beyond the village of Dedikorta, two full days’ walk from the village of Omalo.

It is easy to turn mountains into myths. When we climb, we climb through forests thick and sticky with pine, past ruined villages with stone roofs that have caved in and grown over long ago. We climb up past the tree line and along wildflower paths that give way to endless gold-hued emptiness, interrupted only by crickets with crimson wings: sun-dried grass that stretches beyond our powers of sight. We climb to where even horses do not go, to where the grass gives way to parched and piercing rock. We see nobody. Once or twice, from across a valley, we hear a shepherd call his flock from another peak. Then nothing for hours. When we wake up, each morning, the clouds are at our feet.

These are the mountains the Russian poets loved – Pushkin, Lermontov, Tolstoy. They romanticised their remoteness: Cossacks with their daggers, kindhearted shepherds, the atavistic presence of old gods.

The life of the city – so the Romantic logic went – was only ever a lie. When Olenin, hero of Tolstoy’s A Prisoner in the Caucasus, departs Moscow for the Caucasus, he finds himself in “that happy state of mind in which a young man, conscious of past mistakes, suddenly says to himself, ‘That was not the real thing.’” It is only in the mountains, alongside shepherds, under savage stars, that we find out who we really are: “Perpendicular places,” English poet Lord Byron rhapsodises the region, “where the foot / Of man would tremble, could he reach them – yes, / Ye look eternal!”

Of course, Byron never visited the Caucasus. His Caucasus – drawn from Lermontov’s, from Pushkin’s, from his fervent, feverish Romanticism – is a myth created out of a myth.

For the Russian story of the Caucasus, too, is less simple than Pushkin or Tolstoy would have us believe. The Russian story of the Caucasus is, so often, the story of Russia: of a 19th-century imperial power who sent its impeccably trained soldiers to conquer – and to ‘civilise’. For Lermontov and Pushkin – both at one time soldiers stationed in the Caucasus – the savage beauty of the mountains evinces their need for imperial control; after all, according to Lermontov, “the tribes living in these gorges are savages / their god is freedom, their law is war.”

Today, Georgians have transformed the Caucasus into their own national myth – the mountain people, so any old man in any basement khinkali tavern will tell you, are true Georgians, defended by God and geography from the pollution of foreign influence.

It’s a different story; its meaning is the same. The Caucasus isn’t the “real thing” at all. Rather, it’s a repository of all we believe – and want to believe.

Every story we tell about the mountains is a story we’re telling about ourselves.

“They will talk about this for centuries,” Devi is saying.

If I die, this is where my story ends. They will say: ‘This is what happened to that crazy woman.’

Devi Asmadiredja

She has been gathering hallucinogenic mushrooms – deep speckled red – into her bag. She isn’t wearing gloves. We’ve warned her to be careful – some poisons can soak through the skin.

“If I die,” Devi says, “this is where my story ends. They will say, ‘This is what happened to that crazy woman’.”

She goes on imagining it: how she will be remembered, how everybody will talk. She goes on imagining it until the path rears wildly up.

Then nobody can talk.

We strain our muscles. Our shoes are still damp from the night before. The smell of dirt, cow sweat and river mildew sticks to our clothes. We sleep in abandoned houses, on dirt floors, pressing our backs against the metal of empty bed frames, hiding our faces from the bats that strike their wings against the rafters. We forget to eat, or else we gorge ourselves on bland white bread, tinned sardines, cucumbers sliced with Devi’s precious knife.

I’d imagined that going to the mountains, experiencing the remoteness Devi described, would trigger some Tolstoyan self-understanding. But if I’d come to understand anything at all, it was that in the mountains, the intensity of the cold, the dirt, the muscle pain, the constant banality of survival, leaves no space for thought. We brace our teeth, push through the pain, dull our brains with chacha in the evenings. We watch shepherds as they smear the day’s dirt from their faces and follow the cows for milking – almost 30 cows to milk, twice a day, for a salary of 500 GEL (£137) a month. We do not think about ourselves.

It is only when we find a pair of broken car mirrors in the bathing area of one of the shepherd huts that I realise how dirty I am.

It is the first time in my life I don’t know what I look like.

I think I like it.

I wonder if this is what Devi wanted.

In the village of Dedikorta – four or five still-standing houses, only one inhabited – we sit with shepherds by the settlement’s only fire, cooking in turns, sharing what we have: dried macaroni, chilli sauce in a plastic bottle, boiled dough, the leg of a freshly butchered sheep.

Then Devi takes out her cell phone.

She shows me photographs of her three daughters – 17, 13 and 10 – smiling, in traditional Chechen garb. They live with her mother-in-law now; her husband is in jail. Drugs. She is not allowed to see them. She writes them letters every month: no answer. When the oldest one, Zoe, turns 18, Devi hopes she will come to the mountains and find her. She will understand why Devi had to stay out here – even if it meant leaving her behind.

She tells me the old wives’ tale: women who had trouble with their mothers will bear only daughters.

Sitting by the fire, Devi tells me something else. Devi Asmadiredja, too, is a myth – just like the hermitess of the Caucasus. Something she has created for herself – here, where at last she finally has some space. She spent most of her life as Ariane Clibert: German mother, French stepfather.

“I hate that name.” It didn’t belong to “the only brown girl in East Berlin” – a girl whom her mother, embarrassed to have what Devi calls a “coloured child”, kept at home. A girl who didn’t belong, whom strangers mocked, whom classmates hit. In her 20s, she adopted her Indonesian middle name, the last name of a father she’d never met.

“Everybody needs somewhere to belong,” Devi says. For her, it is Tusheti.

For the first time on our trip, Devi speaks softly, slowly. She does not tell me the familiar stories of her adventures, her bravery, her greatness, the love poems she has received. “Everybody needs somewhere to belong,” Devi says, lighting her cigarette on the fire. For her, it is Tusheti. She is foreign, here – no less foreign than in Berlin – but here it doesn’t matter. The shepherds know her. The locals know her. Here, she can be a legend. Nobody needs to know how afraid she was – we both – when we forded the river she did not recognise.

Devi is the hermit of the Caucasus. She has made sure of that.

It doesn’t matter she forgets the trail, if she breaks her leg for 12 days. She has all the time in the world to find her way back again. There is nothing else she needs to do.

“God – if there is a God – he gave me this life because he thought I could handle it,” she says grimly.

I no longer know if I believe all her stories. But I know that the mountains – dark, vast, annihilating consciousness – are not where Devi, or I, go to find ourselves.

It’s where you go to get lost.

One of the shepherds – a baby-faced 20-year-old called Koba Gogotize with downy hair along his upper lip – beckons us outside. It’s time for a toast: the traditional Georgian way. He fills a hollowed-out ram’s horn with wine – you cannot set it down, and so you must drink it dry – and begins in halting English the ritual toasts of the mountains. To travellers, to new friends, to God.

Then he makes a toast I haven’t heard before.

“To those who die alone,” he says. “To those who have no children. To those who have nobody to continue their name.”

Above us, more stars in the sky than I have ever seen.

We say nothing to him. We drink.