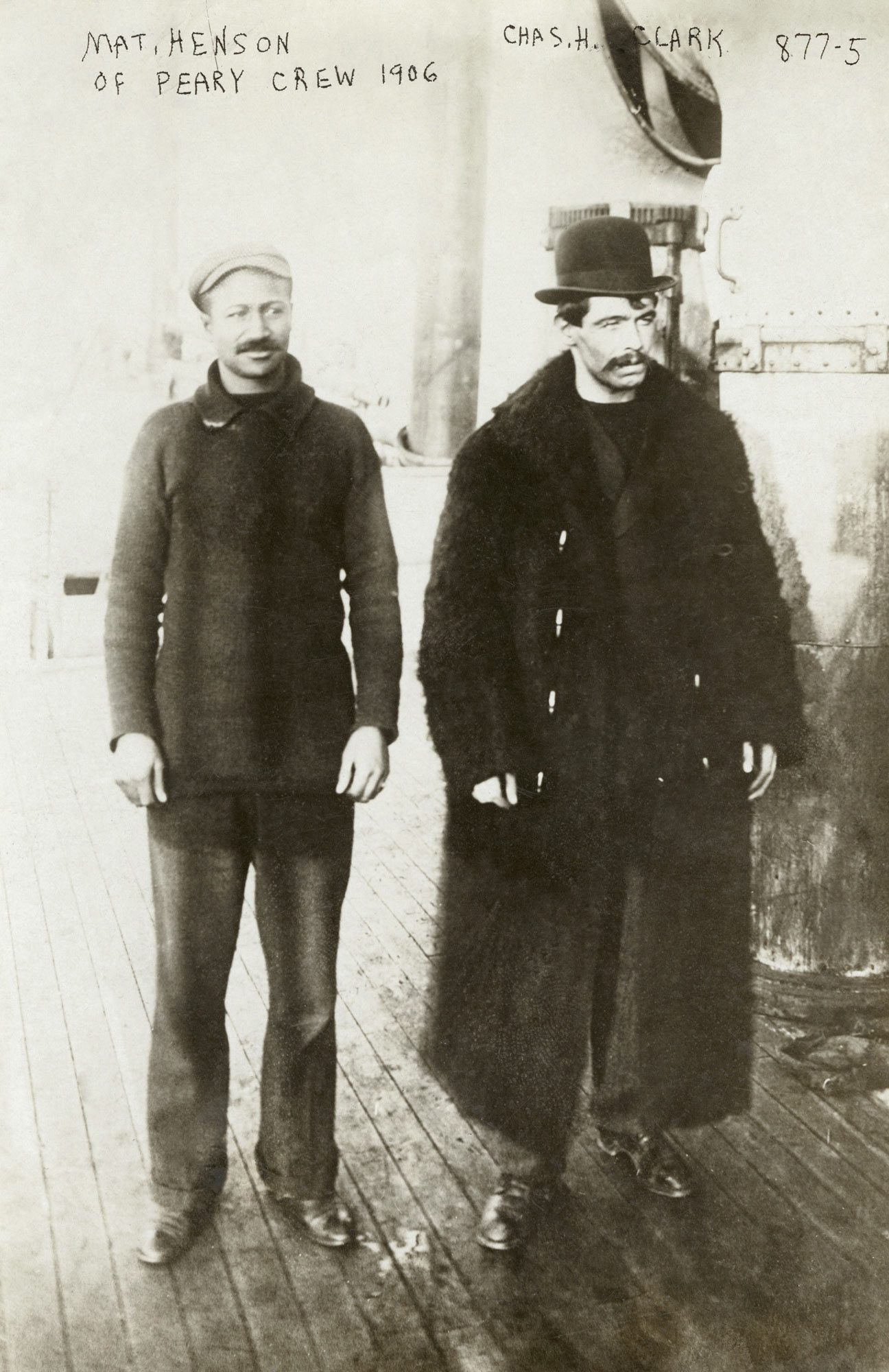

When Matthew Alexander Henson became the first person to reach the North Pole in April 1909, he found himself standing not just at the top of the world but on a cultural fault line. His credentials as an explorer were impeccable – after almost twenty years of Arctic exploration, he had marked himself out from other adventurers by his ability to speak the Inuit language, his skill in driving dog sledges, and his ingenious craftsmanship.

Yet the front page of the New York Times celebrated another man from his trip – the American explorer and United States navy officer Robert Peary. Henson – unlike Peary – was black, so despite possessing a bravery and ingenuity that had surpassed most of his contemporaries, he now had to fight the culturally entrenched racism of the time.

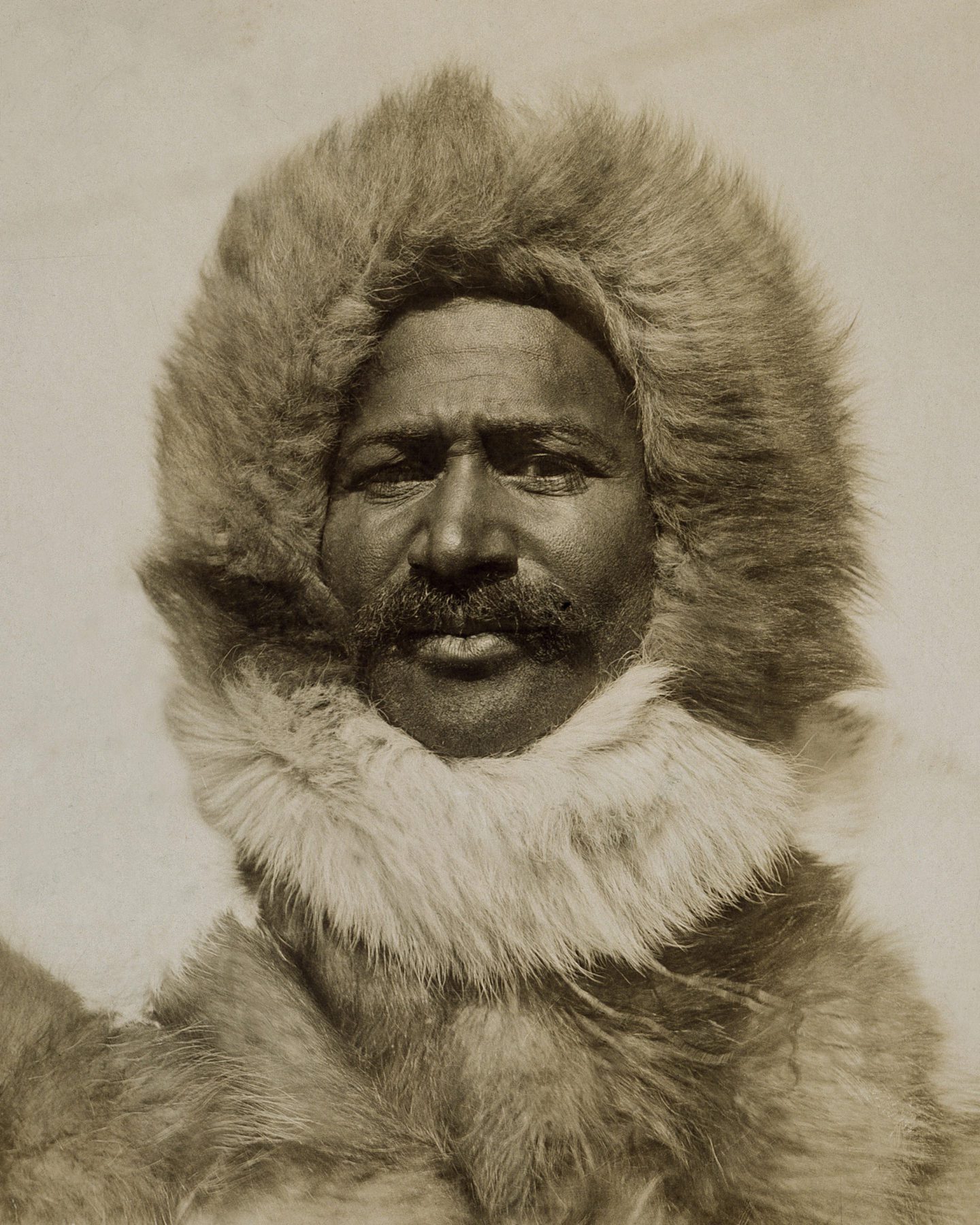

A youthful Henson photographed in 1906 with Charles Clark.

His cause wasn’t helped by the controversy about whether even Peary was the first person to reach the Pole. While the New York Times piece failed to mention Henson, it did talk about Frederick Cook, a man who was claiming that he had reached the Pole almost a year beforehand in 1908. Cook was eventually deemed to be a fraud, but this scandal was superseded by questions about whether Peary and Henson had made the right calculations about where they were from their navigational instruments. Some detractors have claimed that they were as much as 60 miles off course.

Henson was born in 1866 to sharecroppers with a farm near the Potomac River in Charles Country, Maryland. It was just one year after slavery’s abolition in the States, and white supremacists including the Ku Klux Klan, were waging a campaign of anti-black violence, burning houses, churches and schools as they went. Soon his family felt forced to leave the South. Though they escaped the violence, by his tenth birthday Henson was an orphan. At the age of twelve he boarded the merchant ship Katie Hines as a cabin boy. It would be the making of him – in a trip that took him to China, Japan, Africa and the Russian Arctic seas, he acquired both the skills and the taste for adventure that would define him for the rest of his life.

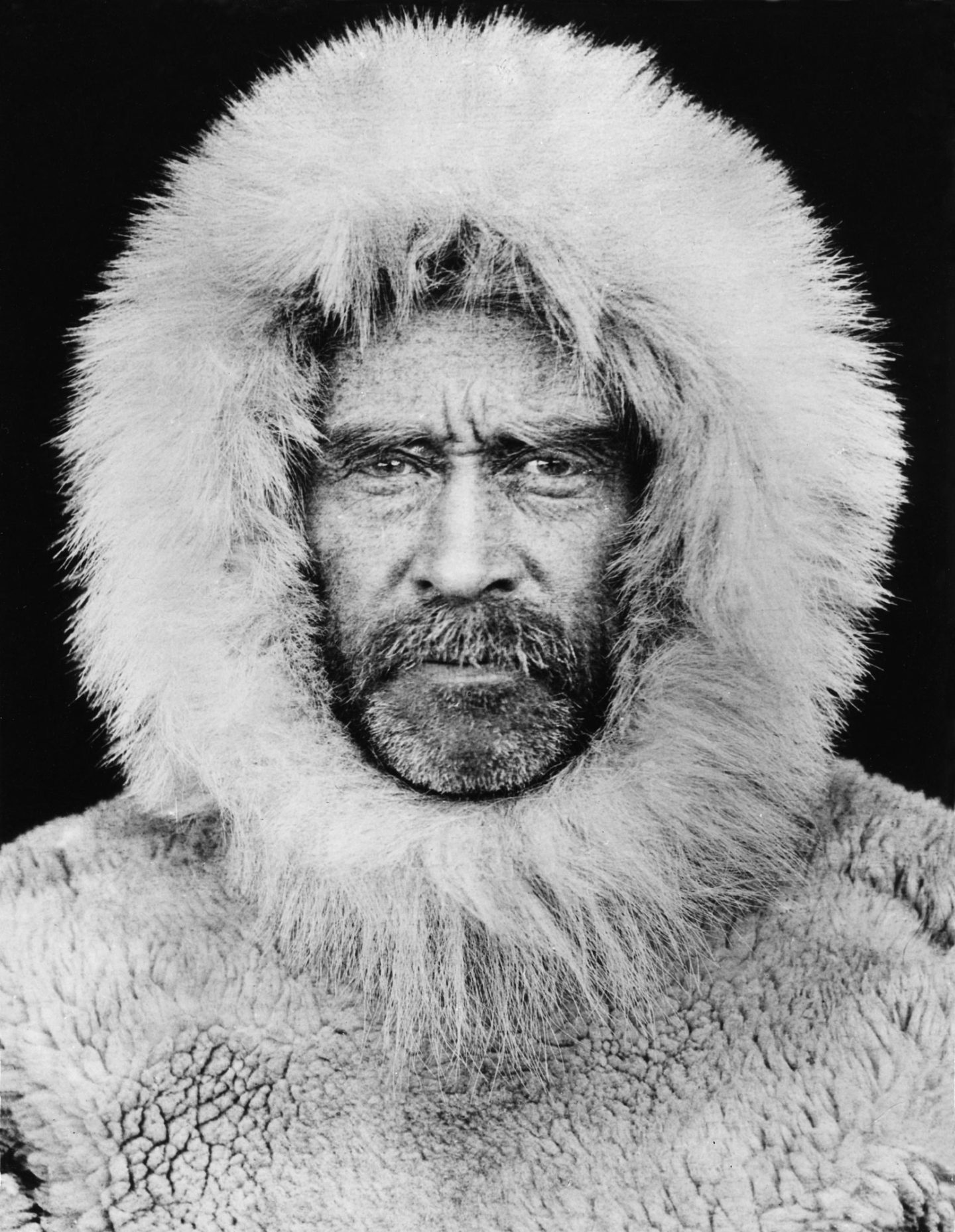

Henson in 1910.

His fateful first meeting with Robert Peary took place when he was working at the Washington DC clothing store, B H Stinemetz and Sons. Accounts vary on the detail – some say Peary had come in to buy a sunhat, others that he was there to sell a collection of walrus and seal pelts that had just arrived from Greenland. Whatever the nature of his dealings was, Henson was pointed out to him as an experienced sailor and Peary recruited him to be his valet for a voyage to survey canals in Nicaragua.

Peary had already travelled to the Arctic in 1884, three years beforehand. After a failed attempt to cross Greenland by dog-sledge he had become obsessed with exploring it further. In Nicaragua he realised that Henson had both the technical skills and the temperament to become a key member of his team. For his next seven voyages, Henson would be his constant and increasingly valued companion.

Peary on the deck of the steamship Roosevelt.

Henson would later write in his autobiography, Negro Explorer at the North Pole, that, ‘The lure of the Arctic is tugging at my heart. To me the trail is calling! The old trail, the trail that is always new.’ Unlike the white explorers on that first trip with Peary in 1891, he quickly acclimatised to travels towards the Pole, devoting himself to learning the language and survival techniques of the Inuits, as well as becoming an expert dog handler. A second trip, to chart the ice cap in Greenland, was less successful – after running out of food Peary and Henson had to eat their sledge dogs in order to survive. Yet still they returned – in later expeditions in 1896 and 1897, they discovered enormous meteor fragments that they sold to the American Museum of Natural History in New York for $40,000, providing funding for future expeditions. In 1906, President Theodore Roosevelt himself supported their trip, supplying an ice-breaker The Roosevelt that allowed them to reach within 174 miles of the North Pole.

On July 8, 1908, they departed on their final expedition, leaving New York Harbour once again in The Roosevelt. By March 1, 1909 they had embarked on sledges from Cape Columbia, and by April 6 they could sense that the Pole was within reach. Crucially Henson travelled ahead mostly by sledge for most of that day – but at the point that they stopped to build their igloos for the night, there was so much mist they could not measure exactly where they were. The next day, when they could take the measurements, they realised – as Henson would tell a newspaper on his return, that – ‘my footprints were the first at the spot’. Peary was devastated. For the long journey home, he hardly spoke to Henson.

The flag that Robert E. Peary flew at the North Pole. Peary cut pieces from the flag and deposited the cut fragments in cairns he erected every time he broke a "farthest north" record. The diagonal piece was left at the North Pole, 1910.

Early 20th century America would tip the balance by unfairly recognising only Peary. On his return in 1909 he was made a Rear Admiral. Henson would merely work as a clerk with the customs house in New York City. After Peary died, Henson’s achievements continued to be largely unacknowledged till 1937 when the Explorers Club of New York made him an honorary member. But Professor Samuel Allen Counter of the Harvard Foundation for Intercultural and Race Relations – who died last year – led a prominent and vigorously researched campaign for Henson to be recognised for his accomplishments. Thanks to Counter’s efforts, Henson was eventually commended by President Dwight Eisenhower in 1954, the year before he died. It was also thanks to Counter – who this time petitioned President Ronald Regan – that in 1988 Henson’s remains and his wife’s were dug up and reburied in Arlington National Cemetery.

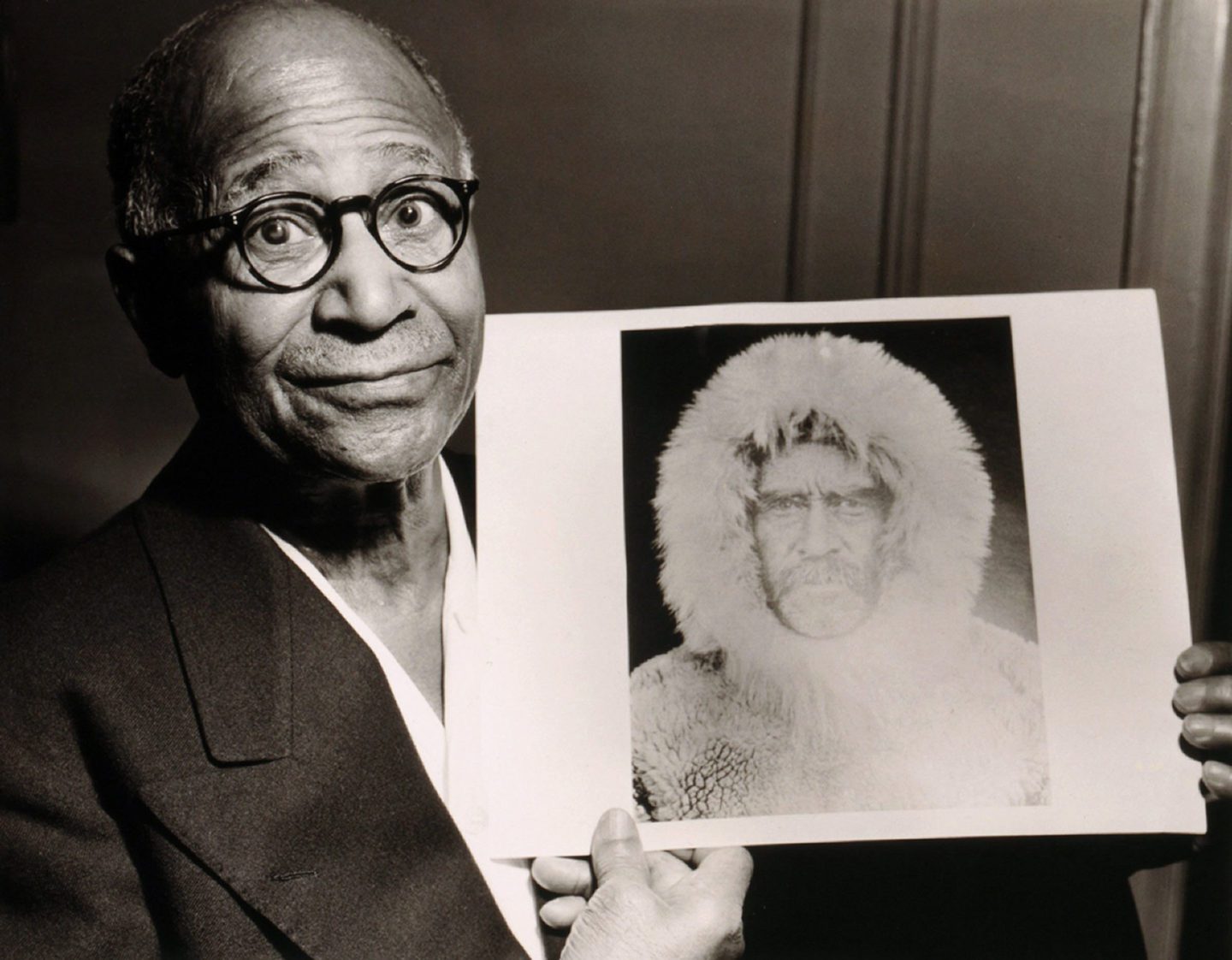

Henson in 1953, two years before his death, holding a portrait of Robert E. Peary, his expedition leader.

An unexpected side-effect of Counter’s research was the discovery that while Henson had never had children with his Western wife, both he and Peary had fathered sons with Inuit women in the Arctic. After extensive enquiries, he tracked these down to Greenland. By the time that he met them, they were both in their eighties, and begged fervently to visit the land of their fathers, along with their children and grandchildren. All were there to witness the reburial – yet further proof of the rich complexity of Henson’s legacy.