Adela Khanum was not above a little light sabotage. She became renowned in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries for the immense power she wielded as leader of the Jaff tribe, the largest in Kurdistan – a position that also made her then the most important woman in Islam. When she first arrived in Halabja with her husband it was a village made of mud huts – but under her rule it transformed into a flourishing trade centre with a new bazaar and fine Persian-style buildings.

Lady Adela Khanum, head of the Kurdish Jaff tribe, a position that made her the most important woman in Islam at the time.

According to one traveller at the time, ‘Such importance did the place attain, that the Turks actually grew jealous, and to obtain a hold over it, put up a telegraph line, to which the tribesmen objected, and expressed their objection by cutting down the wire. At the same time Lady Adela advised the Turks not to repair it, for she too objected to the incursion of Turks upon her territory and warned them that as fast as they built up the telegraph wires her people should cut them down.’

The woman who looks out at us from black and white photos has a ‘don’t mess with me’ stare, a raven-black bob, and a regal tilt of the chin. When the British explorer and diplomat Gertrude Bell met her, she described her as ‘a striking figure in her gorgeous Kurdish clothes with jet black curls (dyed, I take it) falling down her painted cheeks from under her huge headdress’. The intimidatingly named Ely Banister Soane, a British officer and spy in northern Iraq, devoted several pages of his book To Mesopotamia and Kurdistan in Disguise to her. After he met her, as she reclined on a long silk-covered mattress and smoked a cigarette, he wrote:

‘The first glance told her pure Kurdish origin. A narrow, oval face, rather large mouth, small black and shining eyes, a narrow, slightly aquiline hooked nose, were the signs of it; and her thinness in perfect keeping with the habit of the Kurdish form, which never grows fat. Unfortunately, she has the habit of powdering and painting, so that the blackened rims of her eyelids showed in unnatural contrast to the whitened forehead and rouged cheeks. Despite this fault, the firmness of every line of her face was not hidden, from the eyes that looked out, to the hard mouth and chin. Her head-dress was that of the Persian Kurds, a skull-cap smothered with rings of gold coins lying one over the other, and bound round with silk handkerchiefs of Yezd and Kashan. On each side the forehead hung the typical fringe of straight hair from the temples to the cheek, below the ear, and concealing it by a curtain of hair, the locks called agarija in the tongue of southern Kurdistan.’

There is a sad ending to her story – and as too often with the history of this region, it is connected to meddling by Western powers.

Though Soane was a dedicated campaigner for Kurdish autonomy, there’s more than a hint of imperial prejudice in his description. But the overall impression is that he, like most others, found his host formidable. She was born in 1847 into an aristocratic family from the Persian branch of the Kurds. In 1895, the Begzaade chieftain Uthman Pasha – who the Ottomans had made governor of the entire district of Sharizur – took her as a second wife, after his first wife, who had been recommended by the Turkish government, died. The Turks were highly alarmed, and – according to Soane – as Lady Adela went on to acquire ‘much of the power they had given to Uthman Pasha, they furiously bit the fingernail of impotence, and thought of many futile schemes for breaking her influence’.

The fingernail of impotence was destined to remain shrivelled and ineffective, for Adela Khanum (her name translates, roughly, as Lady Justice) had significant talents both as an urban planner and as a business entrepreneur. Her family hailed from Persia’s Ardalan province, once a kingdom renowned for its enlightened rule for art, literature and architecture. Since her husband was frequently away on business affairs connected to his role as governor, she herself commissioned ‘two fine houses’, based on buildings in Sina, Ardalan’s capital, ‘importing Persian masons and artificers to do all the work’. The area was marked by high levels of crime and anarchy, with bandits launching frequent raids on the caravans crossing the countryside, so she also made it a priority to build a prison and court of justice, becoming president of the latter. Further to this she instigated a bazaar constituting four covered rows of shops, connected by small alleyways containing more shops, all, according to Soane, ‘covered in and domed with good brick arches’.

The Jaff tribe became renowned for its discipline and style – and visitors, including Gertrude Bell, the Russian Orientalist Vladimir Minorsky, and the British political officer Cecil J Edmonds were among those drawn to the area by her reputation.

There was growing international fascination with the region, not least due to the British interest in the oil of northern Iraq, and the new German railroad connecting Baghdad to Berlin. As the bazaar flourished, trading cattle skins, wool, tobacco and butter among other commodities, Lady Adela used Halabja’s growing wealth to introduce the Persian style of creating beautiful gardens to the area, with glades of trees sheltering hidden flowerbeds. All this meant that her husband, ‘when he was at Halabja, spent his time smoking a water pipe, building new baths, and carrying out local improvements, while his wife ruled’. The Jaff tribe became renowned for its discipline and style – and visitors, including Gertrude Bell, the Russian Orientalist Vladimir Minorsky, and the British political officer Cecil J Edmonds were among those drawn to the area by her reputation.

There is a sad ending to her story – and as too often with the history, and indeed present, of this region, it is connected to meddling by Western powers. Initially she was supportive of the British, and won their gratitude because she helped advise and protect their soldiers during the fight against the Ottomans in World War I. Further to this, in 1919, when Sheikh Mahmud of Sulaimniya declared himself king of Kurdistan, she joined the British in opposing him. After they appointed her son, Ahmad Beg as the qa’immaqam, or governor of the entire district, Lady Adela essentially continued to exert her power through him.

However, at the Cairo Conference of 1921, it was decided that Kurdish powers should be curtailed. The Kurds’ interests were seen to be essentially subordinate to those of the British, from whom Ahmad Beg was now forced to take orders. Lady Adela was most unamused, and relations became strained. She died not long after, in 1924, at the age of 77.

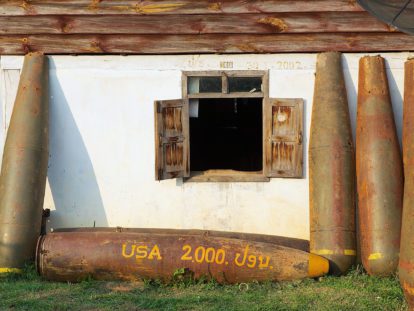

Today, sadly, Halabja is most renowned as the place where Saddam Hussein carried out a chemical attack on the Kurds in 1988, killing over 5,000. Yet as debate continues today over what shall happen to this brave and entrepreneurial people now the Syrian war has come to an end, Lady Adela’s legend is a forceful reminder of what the Kurds were able to achieve when left to their own ingenious devices.