Late last year, the Russian tele-inquisitor, Dmitry Kiselyov, treated viewers of Rossiya 1 to an extraordinary item about Husky (Хаски), aka Dmitri Kuznetsov, 25, a Russian rapper who had recently been arrested in Krasnodar on charges of hooliganism. ‘For anyone who doesn’t know,’ explained Kiselyov to his babushka-heavy audience, ‘rap is a contemporary genre, in which the perpetrator reads out their own spoken-word poetry over a musical rhythm’. Kids are going ‘out of their minds’ for this ‘alternative’ culture, he explained, which defines itself against everything that is mainstream. Kiselyov was sorry to add that it contained a lot of rude words too.

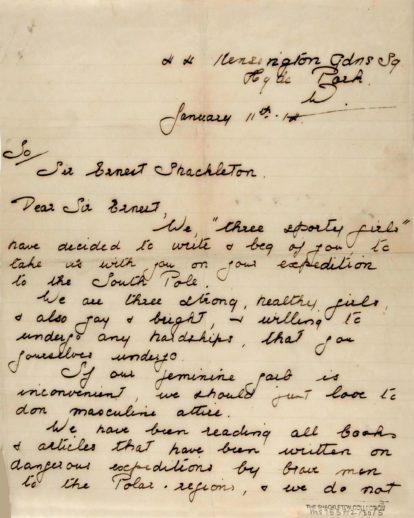

Face has described Russia as an ‘open-air prison camp’ and mocked the Russian Orthodox church in the filthiest possible terms. Photography: Ira Lupu.

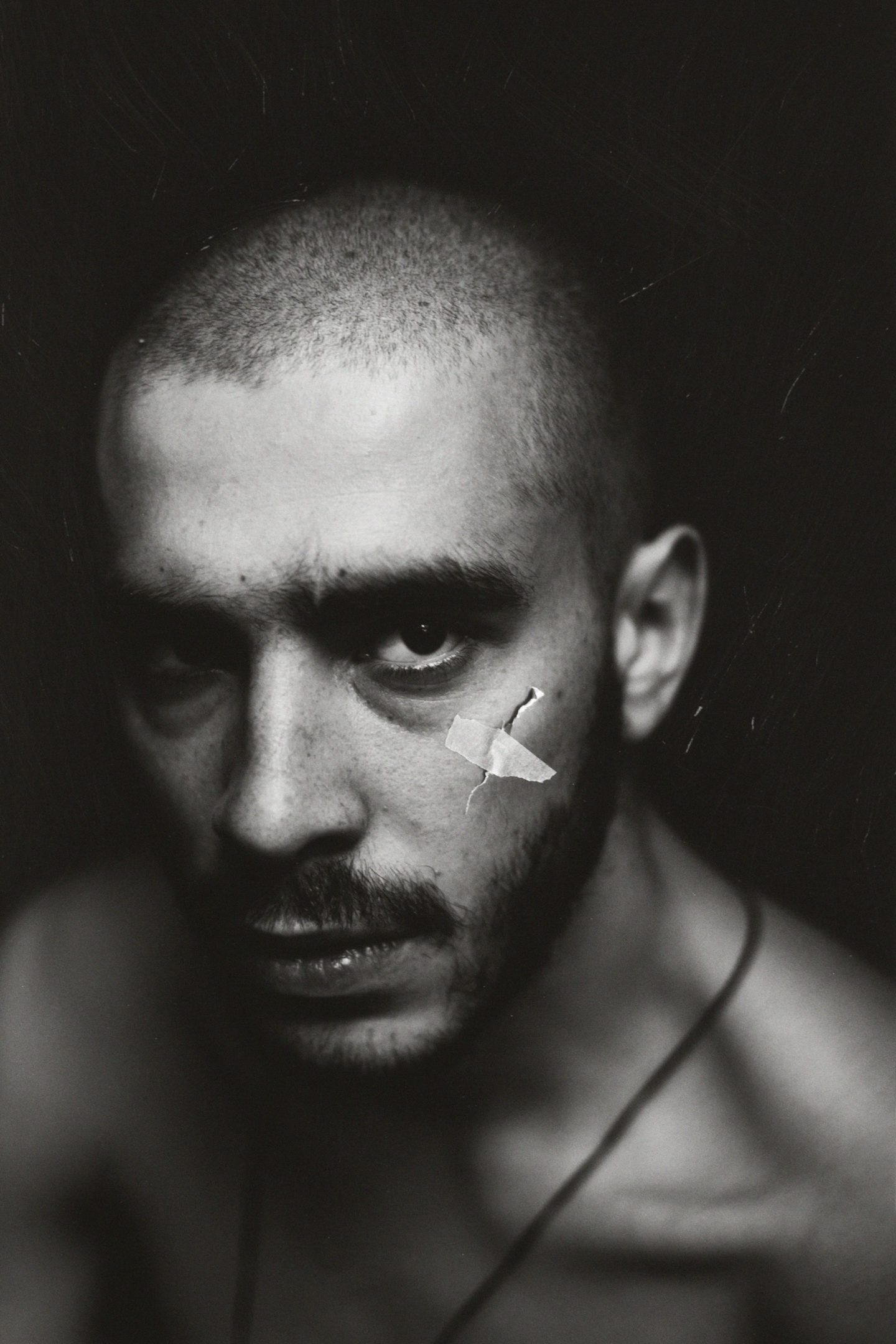

You’d have to go back to the days of NWA or the Beastie Boys stealing VW badges to find such a pantomime of outrage about hip hop on British or American TV. Husky’s particular act of ‘hooliganism’ was to perform an impromptu gig in a carpark after the authorities had cancelled one of his official shows; hooliganism, you may recall, is the same charge that landed members of Pussy Riot in jail. ‘I will sing my music, the most honest music,’ Kuznetsov promised his fans.

But this being Vladimir Putin’s Russia – where ‘Nothing is true and everything is possible’ as Peter Pomerantsev put it in the title of his book – it would be too obvious simply to ban rap. Putin’s communications advisor, Vladislav Surkov, once dubbed ‘the father of Russian PR’ reportedly has a portrait of Tupac Shakur in his office. He once said: ‘The only things that interest me in the US are Tupac Shakur, Allen Ginsberg and Jackson Pollock’. Better to reclaim it. So Kiselyov went on to explain that the music does not come from ‘black America’ as is commonly thought. No, rap is Russian. Vladimir Mayakovsky invented it! To prove his point, the 64-year-old presenter MC’d the Soviet poet’s ‘Хорошо!’ (‘Good!’), composed for the 10th anniversary of the October Revolution in 1927, over a crude breakbeat. ‘Cool, huh?’ he demanded.

Hip hop is the sound of mono-industrial towns left devastated by post-Soviet collapse.

Richard Godwin

He went on to chastise modern rappers like Husky for going on and on about sex, drugs and bling instead of patriotic Russian themes. It’s a shame he hadn’t listened to his own opening clip. If he had, he might have noticed that Husky’s song Пуля-дура (‘Bullet-fool’) disregards exactly what he claims it champions. It begins, ‘I don’t want to be beautiful/I don’t want to be rich’.

Hip hop is, currently, huge in Russia. Its local stars – such as Husky, Скриптонит (Skriptonit), Фараон (Pharaoh), Face, Tatarka and Handy – sell out huge venues and rack up millions of followers on YouTube and VKontakte (the Russian equivalent of Facebook). They have done all this without much help from Rossiya 1 or the more mainstream music channels such as MTV Russia. There is the odd innocuous megastar, such as Timati – who raps about girls and clubs and once put out a song entitled: My Best Friend Is President Putin. But mostly we’re talking about an authentically bottom-up scene through which Russia’s marginalised youth is increasingly channelling its frustrations at the iniquities of society.

Husky, one of Russia’s most notorious rappers, who made headlines around the world at the end of last year when he was arrested after performing to fans from the roof of a car. His arrest was seen as a key moment in Putin’s war against hip hop artists. Photography: Igor Klepnev.

For instance, Face (Ivan Dryomin, 21) has described Russia as an ‘open-air prison camp’ and has mocked the Russian Orthodox church in the filthiest possible terms. One publication has called rap the ‘last bastion of free speech in Russia’ at a time when the authorities are waging war on youth culture. Putin’s government recently announced a new law to protect against ‘blatant disrespect for society, the country, Russia’s official state symbols, the constitution, of the authorities’.

The scene’s best-known icon is Oxxxymiron (aka Miron Fiodorov, 34) who came to international attention when he won a rap battle against the Los Angeles rapper Dizaster in 2017. Oxxxy is by some measure the most successful battle-rapper in the world but he is acutely aware of his poetic lineage too. A Jewish émigré who grew up in Germany and Britain, he possesses an English degree from Oxford, and he’s not afraid to flaunt it. Город под подошвой (‘City Underfoot’) is an account of his tour of the deprived cities that run along the rivers Don and Volga in southern Russia, cities that have been ‘trampled underfoot’. He also finds room to namedrop the medieval alchemist Paracelsus, Gulliver’s Travelsand the Soviet poet Sergei Esenin – he’s the one who daubed his epitaph on a wall in his own blood. But as he notes, Russian rap is ‘multi-party’; there are many different strains. ‘I look in the mirror, and I’m like/“How much trouble have you caused?”’

While he raps in Russian, Skriptonit is Kazakh and proudly draws on Kazakh musical forms. Photography: Igor Klepnev.

Husky has taken direct aim at Putin in the past. His 2013 song Седьмое октября (‘7th October’) is a mock-celebration: “It’s the Tsar’s birthday today… Let’s drink a glass to his patience!” Which makes a lot more sense when you know that 7th October is Putin’s birthday. But Husky generally favours more downbeat social commentary. The monochrome video to Поэма о Родине (‘Poem about the Motherland’) was shot in his hometown, Ulan-Ude in the Russian east – the wrong side of the Trans-Siberian. It doesn’t make you want to visit Ulan-Ude anytime soon – he describes ‘human offal’, ‘children wheezing in their pushchairs’, cranes propping up the sky like crutches. His friends have either been sent to war or they’re in prison. But the chorus runs: ‘My motherland, my love, the view from the window/Is a monotown in a dress of grey cloth’.

A monotown, or mono-industrial town, is a peculiarly Soviet town where they only made one thing. These were the towns most devastated by the post-Soviet collapse of industry and simultaneous removal of social welfare. It seems no coincidence that they’re also the heartlands of Russian hip hop.

Some have made comparisons between hip hop’s popularity and that of the Soviet underground rock scene of the 70s and 80s (the Soviet authorities ultimately thought better of completely suppressing that too). However, as Sasha Rospopina of the Russian gallery, Calvert 22, points out, there are notable differences. ‘Russian rock and pop bands all seem to require external validation from the West in terms of doing covers and inviting Western musicians to play with them,’ she says. ‘Russian rap is the first genre that has managed to build a self-sufficient scene in Russia. These musicians gather big crowds even in small Russian towns, tour the country, sell merch etc – and they don’t need to “make it in the West” to become successful anymore.’ Or as Face puts it: ‘The USA industry can sit on my dick’.

Oxxxymiron (aka Miron Fiodorov, 34) who came to international attention when he won a rap battle against the Los Angeles rapper Dizaster in 2017. Photography: Igor Klepnev.

Rospopina points out that Putin’s so-called ‘war on hip hop’ hasn’t been consistent – this is the regime that pioneered ‘non-linear war’ after all. The recent spate of cancellations and arrests has affected pop and rock groups too; it’s part of a more generalised clampdown on free expression, often with some spurious war on drugs pretext. ‘But I wouldn’t doubt that it is a cause of concern at some government level, especially since they have very young audiences that have become quite politically active in the last years, coming out in protests against corruption and the current government.’

Kirill Kobrin, a Russian cultural historian who was active in the Soviet rock scene, argues that the comparisons only go so far. Rock music was primarily about sound; a feeling of freedom, if you like. But hip hop is by its nature lyrical. ‘Russian culture is especially focused on words – that’s why we have such great literature,’ he says. ‘And it still works. Hip hop is completely focused on the words. People will inevitably talk about how they live. So rap was always doomed to become more and more political.’

It’s also a question of audience. Soviet rock emerged from the cosmopolitan ‘intelligentsia’ in Moscow and Leningrad. The musicians hoped, like their western idols, to become mainstream. But hip hop is the sound of the mono-industrial towns left devastated by post-Soviet collapse, and the ‘dormitory zones’ that skirt the larger cities. ‘Even though it’s very popular in Russia, hip hop is a typical subcultural product,’ says Kobrin. ‘It marks a generational and a social divide. It’s the music of the poorest parts of Russia and the youngest Russians, places a bit like Eminem’s Detroit.’

‘Oxxxy is by some measure the most successful battle-rapper in the world, but he is acutely aware of his poetic lineage.’

Eminem is the western act who seems to have struck the strongest chord with Russian youth: mostly the grainy, battle-rapping Eminem of 8 Mile, though Face occasionally channels the foul-mouthed Slim Shady (‘I fucked Obama’s wife/ Trump’s daughter sucked me off,’ he informs us in Drop the West, which parodies Russian ultra-patriotism). His popularity is in part a reflection of the fact that Russian hip hop is largely white. In Russia the term ‘black’ usually refers to people from the Caucasus rather than of African descent. But that’s not to say that Russia is free of ethnic tensions. While he raps in Russian, Skriptonit is Kazakh and proudly draws on Kazakh musical forms. His breakthrough song VBVVCTND (2014) is an acronym that roughly translates as: ‘No choice, that’s all you gave us’. Face (‘I’m better than Tupac, Biggie, Eminem, Kendrick, J Cole, and even Lil Pump’) is from Ufa in the Republic of Bashkortostan. And as her name suggests, the female rapper, Tatarka, raps in Tatar.

But while Russian rappers occasionally play up the glamour-gap between their own country and America – ‘I pass through these Eastern streets as if I was in Manhattan’, Husky deadpans – the two countries have more in common than you might think. Life in the Siberian rust belt is not so far removed from life in the Midwestern rust belt, endemic drugs, problems and all. Indeed, while there’s a popular notion that Russia is backwards – some years behind the West in terms of popular trends – in some ways the opposite is true. Kiselyov’s claim that Mayakovsky was the first rapper isn’t a million miles wide of the mark; in the 1910s and 1920s, Mayakovsky sought to ‘debourgeoisify’ poetry by using the language of the street, and declaimed his verses in confrontational performances. You could make a plausible case that 21st century Russia in fact represents a sort of neoliberal avant-garde. It was Russia that pioneered fake news and disinformation. And what is Donald Trump but a cheap American knock-off of Vladimir Putin?

In the 1910s and 1920s, Vladimir Mayakovsky sought to ‘debourgeoisify’ poetry by using the language of the street, and declaimed his verses in confrontational performances. Photography: ITAR-TASS News Agency/Alamy.

‘Post-Soviet Russia never tried to imitate western Europe – it went for a very American idea of capitalism,’ says Kobrin, referring to the ‘capitalist shock therapy’ imposed on the former-USSR in the 1990s, which removed the state-owned industries and social welfare in one go. ‘The social situations in America and Russia are getting closer and closer. In America, there are racial inequalities, which exist in Russia too, but they are not so prevalent. Yet there is this huge, horrible gap between rich and poor. And there is no acknowledgment of it from the authorities. There is nothing to the left, or socialist or even centrist from the Government. It is radically neoliberal in social terms.’

All this has had a devastating impact on monotowns, where individuals are ‘drowned like puppies’ to borrow a phrase from Oxxxy. A 2007 study in The Lancet into Russia’s post-communist mortality crisis estimated that over ten million people (mostly working age men) had died in the decade following the imposition of capitalism. Male life-expectancy meanwhile fell from 67 in 1985 to 60 in 2007. It has recovered a bit since then, but it’s still lower than the male retirement age. It’s not wholly surprising that the young men whose cancelled futures these numbers represent identify with a black musical form forged at the harshest end of American capitalism.

There is one striking difference. The American rappers of the late 1980s and 1990s almost all had direct experience of the drugs trade. They rapped about selling drugs both as a violent reality and as a grotesque parody of capitalism. But Russian rap rarely trades in gangster imagery; no one raps about pushing krokodil. It’s less get rich or die trying; more selling merch to make ends meet.

This partly reflects the radically different approaches to free speech in the US and Russia. But as Kobrin points out, the ‘gangster’ space in popular culture is already occupied by Русский шансон (Russian shanson), a form roughly analogous to country music that’s popular in the Russian south. (‘You’re only a thief if you’re caught’ – Russian proverb.) ‘Russian shanson has very close links to prison culture in Russia and strangely, some of its most ardent fans are policemen. So there’s no room for hip hop in this cultural area. That’s why they prefer reflecting on their social injustice. It’s not political. But it’s on the edge of what is supposed to be allowed.’

And perhaps the authorities’ own intense interest in hip hop is only to be expected. It is, in some respects, a gangster state, characterised by machismo, violence, acquisitiveness, paranoia and an inferiority complex on the world stage; all hallmarks of gangster rap. You only need to watch Kiselyov’s amazing follow-up performance to see how deeply he himself has identified with the form. It is a diss track aimed at all of Russia’s detractors on the world stage. As the translation has it: ‘Europe lectures us, foreigners judge us/They’re messing with our imports, mate, and spreading hate/But we’re cool, we’re not taking all their baitin’ fool/We are laying gas pipe bro/Right up all their sanctions yo.’

It’s easy to laugh at this. But in Russia it would be an uneasy sort of laughter. Remember the last lines of Gogol’s classic mistaken identity farce, the Government Inspector, when the real inspector turns on the audience: “What are you laughing at? You are laughing at yourselves!” How do you rebel against a form of authoritarianism that comes wrapped up in so many layers of cynicism and irony? Well, one way is simply to describe your day-to-day reality in as stark a way as possible. Sometimes the truth itself is subversive.