A conversation with Roger Michel is the equivalent of a fast drive through the mountains in a Cadillac – ideas whizz past at speed, jaw-dropping views loom and recede, and there’s a constant, exhilarating sense of uncertainty at what’s around the next corner. The American executive director of the Institute for Digital Archaeology (IDA) is describing a project that would have been considered impossible a short while ago, but now could potentially happen this summer.

The proposal: to use the latest 3D-imaging combined with state-of-the-art laser technology to project the Elgin Marbles onto the Parthenon. ‘We’re pretty excited,’ he declares, ‘we started speaking to the Greek government a year and a half ago, and obviously we have to be very careful about sensitivities. But it would be great to see the Parthenon as it was meant to be seen.’

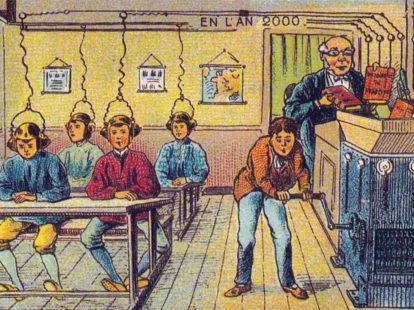

He turns towards Dr Alexy Karenowska, the IDA’s director of technology. In contrast to the flamboyant Michel her conversation is – appropriately for a woman who once wanted to design racing cars – more like a vintage Ferrari, stylishly composed, every word chosen with steel-edged precision. ‘Most people in the UK have heard about the Elgin Marbles, but I’m sure at least 50% would struggle to recognise them,’ she says. ‘What we have is a controversy about the custody of physical objects. Now we have the kind of technology that allows you to recreate them through projected light onto the stone, which raises all kinds of questions about what’s most important – the tangible or intangible aspect of what they are.’

‘Suddenly we discovered there was a whole shadow army choosing to do this work at great risk to themselves.’

Roger Michel

That question of precisely what a monument is – or isn’t – is one that has proved to be of critical importance to the IDA in the last year and a half. When you think, for instance, about St Paul’s Cathedral, is it the Portland stone from which the cathedral is built that gives it its power, or is it its symbolism and history? The conclusion has to be that it is aspects of both – that seeing and walking around a physical structure can be a powerful mental trigger for connecting us with the thoughts and emotions of people who lived centuries ago. So, what does it do to us when that structure is removed, damaged, or obliterated in an attack? That’s a question to which the IDA has being applying a combination of historical restoration expertise and the latest advances in technology to find increasingly interesting answers.

It was Michel who founded the Institute for Digital Archaeology in 2012. He himself has an eclectic background – as you might expect from someone whose favourite film is The Adventures of Buckaroo Bonzai across the 8th dimension, the Eighties sci-fi rom-com in which the star is ‘adventurer, brain surgeon and rock star.’ Although he confesses neither to being a brain surgeon nor a rock star, the Harvard Law School and Oxford graduate is certainly an adventurer, as well as being a trained philologist, a legal expert in forensic archaeology, and passionate advocate for restoration. When he was working with the Centre for the Study of Ancient Documents in Oxford, he started to experiment with innovative technology-driven methods to document and preserve heritage material. Originally the equipment was lab based, but with events in the Middle East making the geopolitical landscape ever more turbulent, Michel saw the importance of developing it to be used in the field.

‘We have the kind of technology which raises all kinds of questions about what’s most important – the tangible or intangible aspect of what they are.’ Illustration: Fede Yankelevich.

The IDA is not the only outfit to be doing this, but the involvement of Karenowska – a talented engineer and physicist who is a Fellow of Magdalen College, Oxford – has introduced technologies that have upped the game of archaeological preservation. In 2015, the IDA launched the Million Image Database, an ambitious project that would work with on-the-ground volunteers to photo-document endangered archaeology across the Middle East and North Africa.

‘It was only once we started recruiting people that we realised the extent of the effort to preserve monuments – these places are important to people not just on a political but a personal level,’ says Michel. ‘Suddenly we discovered there was a whole shadow army choosing to do this work at great risk to themselves, and on their own.’

Many of the volunteers were provided with 3D, or stereo, cameras – designed by Karenowska to cost as little as £20 each – which looked like chunky smartphones. Beyond this, Karenowska was interested in the process of using the images to create full-scale replicas of monuments using 3D printing and machining techniques (in which a computer-controlled cutting tool shapes a piece of raw material). The huge symbolic potential of this suddenly became evident in August 2015, when Isis launched an attack on Palmyra’s ancient archaeological sites, which included the destruction of the Temple of Baalshamin. In the same month, they took Khaled al-Asaad, the highly respected octogenarian keeper of Palmyra’s artefacts, out to a public square where they beheaded him.

Amid the public grief and anger, The Times seized on the story of what the IDA was doing as a powerful way of fighting back against the nihilistic devastation. Dubbing the organisation ‘a team of digital age ‘monuments men’’, the paper described ‘a race against the bulldozers and sledgehammers of Isis [as] it plans to compile 20 million pictures of objects before 2017. Karenowska talks of the article as ‘a turning point – our project went from being something that just a few people had heard of to something with huge momentum, especially in terms of getting feedback and help from people in the region.’ Michel nods, adding, ‘People from regional governments were saying they’d read the article with tears streaming down their faces and wanted to be involved.’

Palmyra, Syria. Image: Giovanni Boscherino.

Michel and Karenowska decided that it was the right moment to initiate the 3D-printing aspect of the project, ‘responding to destruction and defacement with construction’, says Michel. Both are keen to emphasise that the choice of what was reconstructed – the now infamous Palmyra Arch – was not their selection, but that of a consortium of people connected to the site who felt that it evoked Palmyra’s ancient cultural importance. ‘So many white Western journalists said to me, isn’t this cultural appropriation?’ says Karenowska. ‘Yet in the Middle East, not one journalist raised this as an issue – quite the reverse, they were saying ‘This is fantastic, this belongs to us.’’

There were initially going to be two arches, to be unveiled simultaneously in New York’s Times Square, and London’s Trafalgar Square. But in the end it was decided that it would just be the one, which – in an appropriate recognition of its international significance – would be created from Egyptian marble by a computerised stonecutter in Italy. The workshop where it was created was right next to the quarry where Michelangelo acquired the marble for his David. In April 2016, the arch was transported to England in seven blocks, and assembled in Trafalgar Square with steel pins, standing at 6 metres-tall, two-thirds of the size of the original. While many reactions were ecstatic – the then Mayor of London Boris Johnson described it as ‘defiance of the barbarians who destroyed the original’ – some archaeologists were sceptical. Tim Schadla-Hall, a reader in public archaeology at the University College of London told one paper that he approved of ‘collecting a record of and documenting vast numbers of sites’. But the replica arch seemed to him ‘a bizarre expenditure of money, possibly with worthy but misinformed aims, to promote something which isn’t a real past in entirely reproduced form’. The Polish archaeologist Michael Gawlikowski, former head of the University of Warsaw’s Polish Mission at Palmyra, declared the arch to be fine as long it was temporary. ‘Generally, I am against making copies out of context because of the so-called Disneyland effect, but this…draws attention to the problem we have there.’

Both Karenowska and Michel are frank that they encountered scepticism about the project, though they feel the result has silenced their critics. ‘UNESCO was a bit dubious about what we were doing because reconstruction is a complex subject,’ says Michel. ‘Now I would say they are 100% behind us. People at the Royal Academy too were questioning the reconstruction, but after they’d seen it, we heard no more complaints.’ Karenowska concurs, saying ‘I respect people’s views in this area, but it’s one thing if you’re sitting at a computer arguing with the concept, quite another being confronted with the actuality. No amount of verbiage can convey the message of what happens when you’re confronted with a hunk of stone in a public place.’

‘So many white Western journalists said to me, isn’t this cultural appropriation? Yet in the Middle East, not one journalist raised this as an issue.’

Dr Alexy Karenowska

Which, after all, is the whole point. Now two prominent organisations have backed their praise of the project with awards. The British Council has given a three-year grant to the IDA’s Preserving Syrian Heritage Project, while Oxford University has presented Karenowska and the Triumphal Art Project with its annual Vice-Chancellor’s Prize for engagement with research. But neither Michel nor Karenowska are resting on their stone-carved laurels.

Since the arch was unveiled in London it has travelled to New York, Dubai, Florence and Arona. ‘In Florence we were in the greatest art square in the world,’ says Michel, ‘and nobody asked why we had done the project.’ Last December they also restored the statue of the goddess al-Lat from Palmyra, displaying her at the UN. Here they used the combination of stone and laser technology that they are proposing for the Elgin Marbles. 3-D images of the goddess and her smashed up remains were sent to researchers at the Carrara-marble quarry in Tuscany, who restored as much of the statue as they could, and then filled in the gaps with blank stone. The powerful lasers then projected the remaining detail so that al-Lat appeared in all her former glory.

‘In the Middle East, there’s a very different way of looking at buildings and monuments – a greater sense of the ephemeral and intangible aspect of their cultural heritage,’ says Michel. ‘To me it seems that it’s as much about what’s in the viewer’s mind as in the object itself – if you’ll forgive me for the analogy, it’s an almost Obi Wan Kenobi moment. Since the projected light is intangible, ephemeral, it’s a great way of emphasizing the intangibility of what was there in the first place. The technology also allows something to be reconstructed in days, where as with traditional restoration it could take years.’

So what next? The work in Syria is ongoing, while the restoration of Newstead Abbey where Byron lived has been announced. And all the while there’s a sense of the profound impact that restoring inanimate objects has on people’s lives. As Karenowska says, ‘When we present an installation, it’s not just about the physical object, it’s about the communities around it, about messages of peace. The extent to which people understand that is truly extraordinary.’