Sometimes it is what is not true, as much as what is, that defines an icon. When urban myths started spreading in 1969 about the then newly constructed buildings of Grunwaldski Square, it confirmed their status as one of the most exciting architectural events of Poland’s turbulent twentieth-century history.

Some speculated that these futuristic high-rises, dubbed Poland’s Manhattan, had been pre-fabricated and imported from the Middle East. Others theorised that the rounded windows were large convex lenses – still others nicknamed the high-rises ‘the toilet-seat buildings’ because of the windows’ shape.

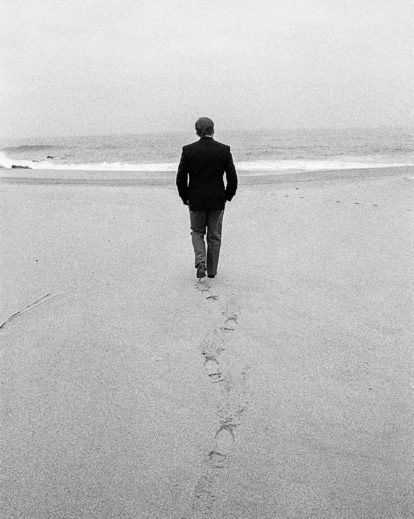

‘Wroclaw was seen as the city of youth, and was to be a bastion of modernity.ʼ Grundwaldzki Square (1963-76). Photography: Chris Niedenthal.

Between the myth and the irreverence there was a no less extraordinary truth. The buildings had been designed by a woman who had been inspired by Le Corbusier and would go on to be acknowledged as one of the greatest Polish architects of her generation.

Jadwiga Grabowska-Hawrylak was born on October 29, 1920, in a small village called Tarnawce in south-eastern Poland. She had initially planned to study at the newly-created department of architecture in Krakow at the end of World War II, but worries about the department’s imminent future meant that she ended up studying in Wroclaw instead.

Residential complex in Grundwaldzki Square (1963-76). Photography: Chris Niedenthal.

It was a decision that would prove fateful both for the woman and the city. Wroclaw had been badly damaged in World War II, when it was occupied by Nazis and known as Breslau. In 1944 Hitler had ordered the city to be turned into a ‘fortress’ against the Soviets, with new fortifications built by concentration camp prisoners. This fortress needed an airfield for supplies, so the workers were forced to destroy the entire residential district along the Kaiserstrasse. Anyone who refused to participate in this destruction was shot.

In the end few planes ever used the airfield. According to historians Norman Davis and Roger Moorhouse in their excellent, detailed book about the city, Microcosm, one of the few planes that did use it was the escape plane of Gauleiter Karl Hanke, the Nazi officer in charge during the Siege of Breslau. Breslau was the last major German city to surrender – by the time it did, between 80 and 90 per cent of it had been destroyed.

‘Grabowska-Hawrylak was one of the architects who was asked to help recreate Wroclaw as a bold architectural statement of socialist ideals.’

Grabowska-Hawrylak was one of the architects who was asked to help recreate Breslau, by then renamed Wroclaw, as a bold architectural statement of socialist ideals. Grunwaldzi Square rose up from the area that had been destroyed to create the military airfield. One of Grabowska-Hawrylak’s challenges was to make sure the design was as financially viable as it was innovative. Some years after the project had been finished, she declared, ‘When I started to design buildings at Grunwaldzi Square, opposite the University of Technology, I knew that one thing was without question: I had to find some way of using pre-fabricated elements to create a non-trivial, original form. Since we couldn’t afford to model each residential building separately, we decided to organise a ‘sculptural’ composition from ready-made, mass-duplicated elements. Concrete proved an excellent material for sculpture’.

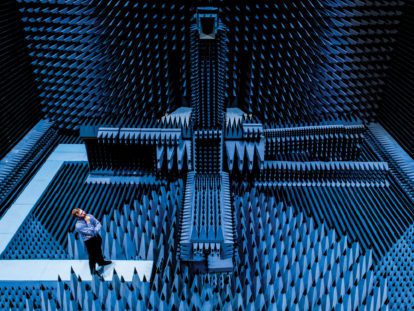

Millennium Church (1990). Photography: Jakub Certowicz.

Monumental architecture and politics have eternally been intertwined, but this was an era in which domestic architecture also carried immense political weight. The Prime Minister of Poland, Józef Cyrankiewicz, was a leading voice calling for greater innovation and experimentation when creating accommodation, saying he wanted it to represent the highest standards not just in the Eastern Bloc, but around the world. Wroclaw was seen as the city of youth, and was to be a bastion of modernity. Through these and buildings that included the Researcher’s House, the Gajowice estate, and the Kollata housing estate, Grabowska-Hawrylak would become synonymous with its recovery.

Researchers' House (1956-61). Photography: Janina Mierzecka.

She died in 2018 at the age of 98. These days she is little known outside Poland, though an exhibition which opened in February this year at New York’s Center of Architecture has been part of an attempt to address that. When you consider how extensive the body of her work is, it’s a scandal that Grabowska-Hawrylak hasn’t achieved greater recognition internationally. Yet Grunwaldzi Square remains an enduring testament to her bold and dynamic outlook, a brutalist symbol of hope after destruction.