Zhakslik Khinzhimbaev has a unit of knowledge that’s of little value anywhere else in the world. Here, though, on the borders of the Aral Sea – a body of inland water divided between Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan – it’s crucial. The knowledge? How thick does the ice have to be to take the weight of a camel? According to Zhakslik, the water needs to be frozen to a depth of at least half a metre if the camel – pulling a sledge piled high with fish – is to avoid plunging into the black waters below.

‘Though the ideal temperature,’ he says, ‘is between –25 and – 40 degrees C,’ – when the ice reaches a metre, the kind of cold that can freeze vodka or cause frostbite in minutes.

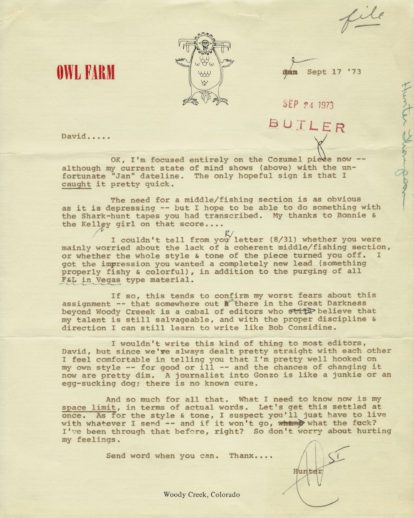

A fishing boat stands stranded. The towns of Aralsk and Tastubek used to support an industrial fishing fleet but the disappearance of the Aral Sea destroyed the industry. Photography: Laurent Weyl/Panos.

Photographer Laurent Weyl submitted himself to the bracing extremes of the Kazakh winter so he could document the lives of fishermen who worked with camels on the edge of the Aral Sea. Zhakslik – a young father with two children, whose own father and grandfather were fishermen – is one of the few of his generation who didn’t abandon the tiny village of Tastubek during the years in which the region was ravaged by man-made drought. Weyl’s images show a winter landscape in which the vast sweep of white makes it look as if the inhabitants have journeyed to the edge of time. There is no sense of any connection to the world’s centres of power here; just the daily existence of people whose lives are etched against a landscape that is as brutal as it is beautiful.

A woman milks a Bactrian camel while its calf feeds from another of its four udders. Photography: Laurent Weyl/Panos.

Yet it was decisions taken in the former Soviet Union’s centre of power that led to the Aral Sea becoming what was described by former UN Secretary General, Ban Ki-Moon, as ‘one of the worst environmental disasters of the world’. Moscow’s dream of turning its Central Asian territories into a hot spot for cotton-production led to first Stalin and then Khrushchev implementing ambitious irrigation programmes to divert water from the sea and into the desert. Stalin’s Great Plan for the Transformation of Nature was launched in 1948, followed by Khrushchev’s 1953 Virgin Lands Campaign. Two of Central Asia’s greatest rivers – the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya – were channelled into thousands of miles of canals, which allowed Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan to become cotton producers, the latter one of the world’s largest. By the early Eighties, the Soviet Union was seen as the world’s leading supplier of ‘white gold’.

Zhakslik has a unit of knowledge that’s of little value anywhere else on earth: How thick does the ice have to be to take the weight of a camel?

Since both rivers flowed into the Aral Sea’s basin, the impact on what was once the world’s fourth largest body of inland water was devastating. In the 1960s the water began to recede from the shores and by 2000 it had split into two lobes, the North (Small) Aral Sea in Kazakhstan and the South (Large) Aral Sea in Uzbekistan. The large Aral went on to shrink further into eastern and western basins; by 2014 the eastern basin had entirely evaporated. What had been sea was now a toxic desert of salt, fertilisers and pesticides, dotted by ship graveyards filled with rusting maritime hulks.

Sabira Ibragieva, a blind 60-year-old former teacher, can remember when the first signs of desiccation started to appear in Tastubek. ‘We started to notice the sea was drawing back in 1967,’ she declares. ‘It wasn’t long before people started leaving the village. We used to have everything – electricity, shops, a post-office, a leisure centre, 300 houses…But the brick buildings crumbled, and we had to salvage wood, metal and glass to get what little we could from the relics.’

Sabira Ibragieva, one of the residents of the former fishing village of Tastubek, is now blind but she remembers witnessing the Aral Sea receding in 1969. Photography: Laurent Weyl/Panos.

By 2010 the inhabitants of Tastubek needed to travel over 80km simply to reach the sea. Yet if it was a slog to get there, once fishermen like Zhakslik reached it, there were still worse problems. In its heyday the Aral Sea had provided the Soviet Union with a sixth of its fish. But another consequence of the sharp reduction of water levels was an increase in the concentration both of salinity and of the pesticides washed into the sea. Many fish died, and those that survived were essentially toxic. Once there had been more than twenty species, including sturgeon (Tastubek was formerly famous for its production of caviar), silver carp, bream and roach. Of these the majority disappeared.

Regeneration

In 2005, an $86m World Bank-funded dam and restoration project was launched in Kazakhstan to revive the Syr Darya. The results were dramatic – an 11-foot surge in water levels after a mere seven months, beating scientific predictions that it would take three years. In 2019, fourteen years after the project began, the sea is fewer than 20km away from Tastubek. The fish are reappearing – more than 15 kinds according to some sources – and fishing production has soared from 600 tonnes in 1996 to 7,200 tonnes today. A second phase of the dam project is in advanced planning stages.

A man and his camel depart to fish in the Aral Sea. A camel can only walk on ice if it is covered with snow. Otherwise, the hooves will slide on the ice. Photography: Laurent Weyl/Panos.

Today Zhakslik can make his family’s living from the sea again. Each winter he ventures across the ice with his Bactrian camels – their cumbersome silhouettes looming against the white like the afterthought of some hungover creator. He and his fellow fishermen create a hole every ten steps that they take, carefully positioning the floats attached to their net before eventually sliding it into the water. It takes immense skill and effort to do this properly – once it’s been done, a baton needs to be installed as a marker so that they don’t lose the net.

At the start of every day the men take a modest breakfast, generally consisting of a cup of tea with milk and a little bread baked the night before, and butter. The bread is fried and has a strong salty taste. What’s extraordinary is that once they’re out on the ice they will eat nothing for between ten and twelve hours. This is despite the fact that they will be engaged in heavy physical labour, often hauling in the nets and cleaning the holes with their bare hands. According to Zhakslik, ‘If I bring my gloves along they will freeze, and then I won’t be able to work anymore’.

While the men conduct their chilly vigil, the camels stand and look on impassively, occasionally snacking on branches, or the odd fish stolen from the catch. They are as integral to these men’s lives as the fish. As well as providing what – to the outsider – looks like a surreal form of transport in a snowy landscape, they are viewed both as a prime source of food and as a marker of social status. One camel can provide meat for a family for five months during the winter. They are also presented as gifts at the time of weddings and the births of babies. Beyond this, when spring comes, the camel’s wool is shorn off so that women can make warm shoes and waistcoats with it and sell them. The camels are also milked on a daily basis, producing a liquid that is like a slightly stronger version of cow’s milk with a bitter aftertaste. Sugar, boiled in camel milk before being hardened, provides a popular local sweet.

A gate built at the entrance to Aralsk. Photography: Laurent Weyl/Panos.

How long will it be before they are replaced by motorised transport? Not for a while it seems. Right now the international focus is on what happens below the waves – Zhakslik talks about how he and hundreds of other fishermen in the area have become members of the Danish NGO ‘Society for a Living Sea’, which provides advice on how to keep the marine environment healthy. A key concern, for obvious reasons, is sustainable fishing, not least during the winter. The kambala, or flat fish, is the most common fish caught at this time of year. Initially it was a species introduced by the Soviets in the Seventies as a measure to slow down the decline of the fishing industry. Now it’s helping coastal villages to regenerate themselves. Zhakslik declares, laughing, ‘The Danes even taught us recipes for cooking it’.

A local fisherman pulls a sledge across the vastness of the landscape toward his fishing spot on the Aral Sea, a few kilometres from the village of Tastubek. Photography: Laurent Weyl/Panos.

While financial circumstances are improving for the community, there is still much they cannot take for granted. Health concerns include widespread respiratory problems connected to the pollution, and infant mortality rates remain high. When Weyl was spending his time in Tastubek, there was also no mainstream electricity there, despite repeated promises from the government to extend the supply from the nearby village of Jambul. During the long, cold dark winters their lighting was provided by petrol lamps. Some of them had televisions, but they were sustained by generators and only broadcast two channels.

Once out on the ice the fishermen will eat nothing for between ten and twelve hours. This is despite the fact that they will be engaged in heavy physical labour, often hauling in the nets and cleaning the holes with their bare hands. Photography: Laurent Weyl/Panos.

Flat fish (Kambala) frozen in the Aral Sea. Photography: Laurent Weyl/Panos.

Poignantly, Zhakslik talks about the ship graveyards as a symbol of what the people have been through. ‘The image is so well-known,’ he says, ‘that people make a pilgrimage here just to see the boat cemetery. What none of them realise is that the villagers maintained these grounded trawlers for decades. The whole time they were hoping for the sea to come back. Then, after eighty years, when nothing significant had happened, they decided that it was all over. So, rather than leaving the wind and sand to do their work, they emptied them of everything that was useful and set them on fire.’

An abandoned industrial building in the former port of Aralsk. Photography: Laurent Weyl/Panos.

Fish drying on racks in an industrial building bought by the Aral Teniwi Association to convert into a fish packing plant to help local fishermen sell their fish at reasonable prices. Photography: Laurent Weyl/Panos.

Yet now there is a chance of something rising from the ashes. Gradually people are returning to the region to make a living. Another Danish initiative, the Aral Tenzi Society, is helping women set up factories for making bread and packaging the fish. On the Uzbeki side, last year, a major electronic music festival saw thousands of people calling for the similar revival of their part of the sea. If the next phase of the World Bank project goes forward, the walls of the dam will be raised by four metres, helping keep an additional 15 billion cubic metres of water in this region, and extending the area covered by the sea by another 150 square miles. As the fishermen with their camels have witnessed, as long as the water levels continue to rise so will the opportunities.