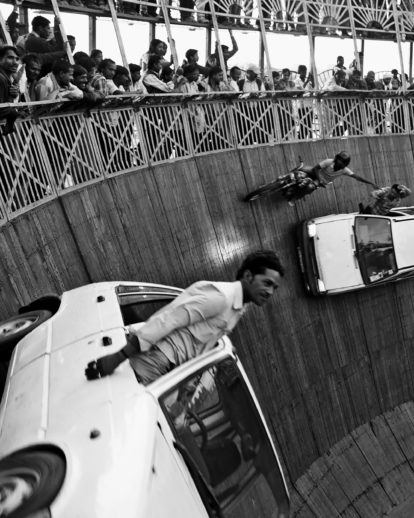

‘It looks like you’re on the moon.’ The camera pans to a dramatic snowscape, the eery half-white of the ground contrasting with a luminous swirl of grey sky. Small human figures wrestle with a vast observation post, a white hut perched on top of a skeletal black metallic structure that looks as if it could be an invading Martian. Yet this is not extra-terrestrial footage, but the Canadian Sub-Arctic. Churchill, Manitoba to be precise, capital – as one of the documentary interviewees proudly explains – of polar bears, beluga, and Northern Lights.

Bare Existence: A Documentary Film

Video Duration

Like any powerful narrative, Bare Existence – a short film made in conjunction with Canada Goose – takes what we think we know and makes us look at it through new eyes. The polar bear has become such an ubiquitous symbol of global warming that sometimes we forget how to feel the horror and anger that we should at what’s happening to this species. By highlighting how seemingly alien and hostile the landscape in which a polar bear lives is, director Max Lowe makes us think again about how extraordinary the animal must be that till now has been able to survive nature’s harshest elements. The film focuses on the work of Polar Bears International (PBI), the non-profit organisation of scientists, conservationists and volunteers that dedicates itself to studying the polar bear and its changing circumstances and communicating that information to the rest of the world.

‘We can think of these bears as messengers. These kinds of events unfolding in the Arctic can tell us what kinds of events are to come to all of us.’

Dr Steven Amstrup, chief scientist, PBI

‘Polar bears can walk thousands and thousands of kilometres every year in search of food.’ World-leading polar bear expert, Dr Steven Amstrup, is chief scientist at PBI, and has campaigned for decades for governments and corporations to recognise how the fate of this species is a harbinger of global disaster. ‘The distance they cover is much greater than that, say, of the great migration of the wildebeest in Africa, or the porcupine caribou in Canada.’

It’s not surprising, then, that a study in Science two years ago showed that polar bears burn a massive 12,325 calories a day. Their main source of food is seals, which, according to Dr Amstrup are ‘basically giant fat pills’. Polar bear fur isn’t, as many people assume, white, but is in fact translucent, ‘They look white because ambient light is typically white, but if you see them in the early morning they might look more grey, if you see them in the setting sun they might look more rose coloured or pink.’ As with some other species, most notoriously the flamingo, their diet contributes to their colouring, ‘though there’s not much dirt in their environment, they’ll get the oils from what they’re feeding on,’ he explains. ‘So gradually their fur takes on a yellowish tinge through the course of the year.’

‘It looks like you’re on the moon’: The Canadian Sub-Arctic

A particularly interesting point of comparison is the brown bear, with whom they share an ancestor, ‘but the grizzly bear only has a tenth of the home range – if you look at them both, the polar bear is sleeker, has less of a pronounced shoulder hump, and is longer and taller. People think they’re built that way for swimming, but in fact they spend much more time walking. The shape of the head is very different too – it’s narrower, more pointed, more of a Roman nose if you will. That’s because they’re shoving their faces into snowbanks and into breathing holes (in the ice) to try and catch seals.’

We are worlds away from this extraordinary evolutionary specimen, sitting in the kind of Soho club where the predominant white fluffy substance is the froth on artisan coffee. Dr Amstrup has come to London for a screening of the documentary. In it, we – along with him and his team – will witness some of the most devastating consequences of food shortages for the polar bear community of Manitoba. In one particularly harrowing scene, we will watch a polar bear cub go into convulsions just minutes before it dies of starvation.

‘Polar bears depend on the sea ice to catch their prey,’ Dr Amstrup explains. But according to a recent government survey, in Northern Canadian waters the sea ice has been declining by 7% a year since the late Sixties and has now reached catastrophically low levels. Forced onto land for longer periods of time, polar bears, who can build up fat reserves that allow them to fast for 10 months and sometimes more, are now resorting to desperate measures to replace the seals in their diet. In extreme conditions, this is leading to cannibalism.

The most desperate, heart-aching scene in the entire documentary is the moment when a mother bear goes after two male polar bears who have killed her cub and eaten it. We see them, the fur around their mouths blotched with gore. Once they have moved away, she goes in and poignantly retrieves her cub’s remains, which by now are little more than blood-stained fur. As she drags it away, it’s as if she’s trying to salvage some last shred of dignity for the cub that she was powerless to save.

From his own extensive research, Amstrup has predicted that the decline in sea ice will mean that the world’s polar bear population will be reduced to less than 10,000 by 2050. On the film we hear his voice crack as he talks of the point, in May 2008, when because of his testimony polar bears were labelled a ‘threatened’ species. ‘That was the single biggest accomplishment of my career,’ he says. Twelve years on, ‘we haven’t really done anything to save polar bears’.

At the end of the film, the silence in the auditorium is tangible. Then Amstrup comes on stage to be interviewed about the complex challenges facing those who are trying to bring about change. He talks about a report he has read on the plane on the way over, investigating the thousands and sometimes millions of pounds being spent by leading energy companies on misleading climate-related branding and lobbying. What’s most clear is that there is no time to prevaricate – and for those in doubt about what to do, he presents a simultaneously clear and sophisticated strategy.

The first point of action is, quite simply, communication. ‘Tell your friends, your family, the people you go to social clubs with, to youth groups, to church, synagogue, wherever you encounter people. Write to your member of parliament, write to your prime minister,’ he declares. We are in an age where social media means that the informing others of your opinions has never been more political, but he emphasises we should make our environmental intentions explicitly so. ‘Vote for members of parliament, for prime ministers, for senators, for congressmen who actually have made it clear that they care about our future,’ he continues. ‘Because the behaviour of most politicians round the world is that they don’t. So we’ve got to change how we vote.’

It is predicted that the decline in sea ice will mean that the world’s polar bear population will be reduced to less than 10,000 by 2050.

As his earlier comments have indicated though, it is the corporate challenge that is the greatest. ‘Vote in the market place,’ he says. ‘With your dollars, with your pounds, with your euros. Support companies that have a sustainable business model. Support companies that say they care about the long-term welfare of everyone and not just the short-term welfare of their shareholders. That’s been a real critical issue. All our economy is based around quarterly reports and not looking at the long-term impact.’

The work of PBI has been supported by Canada Goose since 2007 – in the intervening period it has donated $4m, which Amstrup tells me ‘has given us a much bigger megaphone than we otherwise would have had.’ Certainly this film should bring renewed impetus to the organisation’s cause. For even as we watch the desolate alien landscapes against which the tragedy of an entire species is playing itself out – grey skies split by a white sun, strips of snow next to jagged mosaics of ice, the sheer howling whiteness – we know this is a story that is resonating closer and closer to home. After all, as Amstrup says, ‘We can think of these bears as messengers. It’s a tragic message, but these kinds of events unfolding in the Arctic can tell us what kinds of events are to come to all of us.’