Magali Côté has risen at sunrise to light a fire on the surface of the frozen lake in which she has spent six hours freediving the day before. ‘To be a successful freediver you have to be able to empty your mind. Just concentrate on your heartbeat. And bring it lower.’

‘It makes me feel really alive when I’m diving,’ she says. ‘You know anything could go wrong. So you have to put yourself in a really Zen zone. It’s the complete opposite of an adrenaline rush.’

Magali Côté warming by the fire in the early morning hours, Little Cove, Tobermory, Canada. Jacket by Parajumpers.

‘YOU KNOW ANYTHING COULD GO WRONG. SO YOU PUT YOURSELF IN A REALLY ZEN ZONE. IT’S THE COMPLETE OPPOSITE OF AN ADRENALINE RUSH.’

Magali Côté

As well as being an experienced freediver, Côté has worked for many years as a commercial diver on projects including hydro dams, bridges and wharfs, pumphouses, and other underwater structures. Doing maintenance and underwater welding sounds more fraught than performing a freedive in the translucently beautiful Little Cove in Tobermory, Canada. But according to Côté, it requires a similar kind of mindset.

‘If I was stressed I would not be able to weld under water. First of all, it’s very uncomfortable. Second, if you don’t have the patience to accept that you’re not feeling the best, it becomes a problem – mentally you always have to be able to move forward.’

Axe and monofin in hand, Côté approaches the frozen lake, Tobermory, Canada.

Côté can remember wanting to dive when she was a toddler. ‘I actually have photos of myself, aged two or three years-old, trying to wear my dad’s scuba gear. Of course it was much too big, but I would still put the hood on and walk around like a mini scuba diver.’

She gained her PADI (Professional Association of Diving Instructors) qualification in diving when she was in her late teens. ‘There are different [speciality] certifications that you can get – like wreck diving – but the one I wanted to do was in ice-diving. Even then all I wanted to do was explore the unexplored.’

Walking to the middle of the mound of ice. The cove and much of Georgian Bay was entirely frozen on this day, and yet some of the ice had melted in a circular shape creating a fascinating ring around a fresh mound of ice and snow in the centre.

It was also when she was in her teens that Côté was diagnosed with ADHD. At first she took medication for it, but then she realised that her passion for diving provided a way of controlling it without pills. ‘Life was difficult for a while. I was trying to find myself in the chaos. But then I realized that listening to music with no lyrics or doing a lot of sport really helped me. Freediving has helped me even more – you know you have to concentrate on just one task in order to achieve it.’

When she was working as a commercial diver ‘I was wearing this heavy gear – I would weigh 300lbs with all of it on. That was a lot of stuff to carry.’

Côté discovered freediving after moving to the west of Canada – ‘I’m from Quebec. I moved west because of the mountains as well as the amazing diving. For a while I worked as a millwright [dismantling and repairing machinery]. I found some amazing jobs. But I wasn’t spending any time in the water. I realised I had to go and chase my passion. After doing my research, I found a course in freediving in Maui, Hawaii. That was four years ago.’

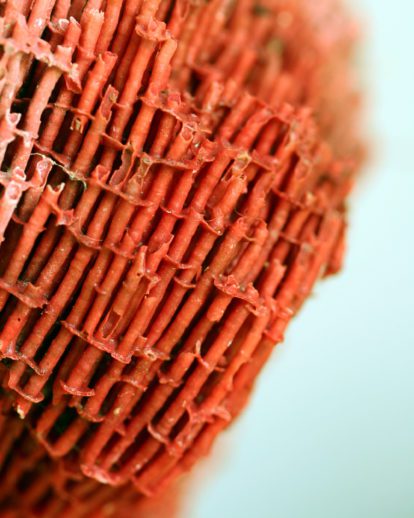

Chopping through nearly two feet of ice. A good pre-dive warm-up that is welcomed by ice divers when the temperatures are cold.

Freediving on its own presents extraordinary technical challenges, which are inevitably added to when that diving takes place in sub-zero temperatures. Côté says that when she was living on Vancouver Island in 2016, she started to practice in a lake in order to get around the restrictions imposed on freediving in swimming pools. ‘Then the winter came,’ she says. ‘When the temperature dropped I thought, ‘That’s a real challenge. Let’s do it.’ I kept showing up in a bathing suit, and a lot of people were telling me, ‘You’re going to get sick. You’ll get pneumonia.’ But I ignored them. And I didn’t get sick.’

Resting in the hole in the ice. Often freedivers will take anywhere from 1-4 minutes of ‘breathing up’ before they perform another dive to relax the mind and replenish oxygen; Right: Performing a ‘duck dive’ with monofin. A duck dive is where the freediver goes down head first, hinges at the hips, and lets the weight of the body initiate the descent into water.

‘I started to do research and realized that there are so many studies that show the health benefits of cold water. It’s well known that Scandinavians will take a hot tub and then jump in the snow. It’s so good for you, not least because it releases endorphins. It also releases antioxidants which stop you from getting sick.’

Côté created headlines when she went diving on New Year’s Day 2017 in a frozen lake on Vancouver Island. Photographer and fellow diver Eiko Jones, who recorded her achievement, conceded that what she was doing was dangerous, adding, ‘Everything has risks, but properly managed, things are fine.’ It’s a statement that could well be Côté’s mantra, who as a commercial diver has been responsible for the safety of entire teams underwater. ‘There are different ways to do a job,’ she says, ‘but the most important is to do it safely and not put anyone at risk.’

Magali Côté wears jacket by Parajumpers.

Above water, she has a more impulsive side. Last year she sold her house on Vancouver Island and ended up in California staying with a friend. ‘I wanted to have my motorbike there, so I flew back to Canada to get it. Then I rode to California with a spear gun, dive gear, an underwater camera and a microphone and interviewed divers along the way. I want to call it ‘Stories from the Ocean’. It was so much fun. I made it my mission. It was all about what I love doing the most.’