I can’t breathe. The only sound I hear are thunderous cracks, so loud they shake my body. Another crack, then another. I open my eyes and see in all directions nothing but gradating bands of blue and black, like a Rothko painting. I must be getting close now. I kick myself deeper until I hear a beep. It’s coming from my wrist, my dive watch. I glance at the screen and see that I’m five storeys below the surface of the ocean.

What I’m doing is called freediving – using my natural body, without the aid of any machines, to dive deep beneath the ocean’s surface on a single breath. Thousands of people freedive as a sport, pushing themselves to depths as low as 700 feet on a single breath. But I have no interest in that kind of often lethal, competitive agony. I’ve come to the deep water of the north east coast of Sri Lanka for a more beneficial purpose, to practice a different kind of freediving. I’ve come here to try to communicate with the world’s largest predators: sperm whales.

Leading the expedition is the man floating beside me, a French engineer named Fabrice Schnöller. For the past seven years Schnöller and a ragtag international crew of world champion freedivers, coders, computer engineers and physicists named DareWin have been researching sperm whale vocalisations – the thunderous cracks shaking my body – in the hopes of translating them and, perhaps one day, beginning a conversation with these animals.

When you are freediving in the Azores you are already at the western part of Old Europe, almost mid-distance from what they call the New World. The light here is great. We are recording whale ‘clicks’ here with the new sound recording software we have developed.

Researchers have known for more than 60 years that sperm whales and other cetaceans communicate with extremely loud vocalisations called ‘clicks’, which the animals emit from their noses. We know these animals are ‘talking’ to one another, we just don’t know what they are saying. In the next two years, DareWin hopes to find out.

Schnöller and I have just reached a depth of 60 feet. The clicking has got louder. Through the diamond- clear water, I can just make out through my dive mask two black scuds in the distance; every few seconds the masses grow larger and larger, like ink blots on a napkin: two sperm whales, a mother the size of a school bus and her calf, the short bus. As the whales advance, I can feel the clicks penetrate my chest cavity.

Sperm whales are the loudest animals on the planet. Their clicks can be heard by other whales for hundreds of miles across the ocean; some researchers believe sperm whales use clicks to stay in contact with one another across the globe. The low frequencies in the vocalisations are so powerful they can blow out human eardrums and shake our bodies to death.

Whales dive down to 1,000 feet for 45 minutes, or even an hour to feed, then back to the surface. Sometimes they stop feeding to socialise. Their intelligence is evident: when they communicate with each other they change sounds and might even have accents and sublanguages.

But the pair of whales in front of us isn’t likely to kill us. The clicks they are sending are relatively soft and shake my body only mildly. These are the exact kinds of vocalisations Schnöller and the rest of the DareWin team have travelled 10,000 miles to collect, in this deepwater trench.

Beside me, Schnöller kicks himself deeper and holds up a handmade audio rig with stereo hydrophones on its sides. He uses this contraption to capture HD recordings of clicks for later study back in the lab. DareWin believes that inside the clicks now shaking our bodies, is encoded information, a kind of language, shared by sperm whales and perhaps other cetaceans. However, this language is made of pictures, not words.

Schnöller beckons me a little nearer, a little deeper down, to get a closer look, a better listen. Then he motions to me to stop and stay perfectly still. The sperm whales begin charging us now, their locomotive-size bodies cutting through the water at 20 miles per hour. I don’t blink, I don’t move. I just float there, six storeys beneath the surface, holding my breath, and try to trust this moment.

To understand how revolutionary – and controversial – DareWin’s work is, you first need to understand how sperm whales and other cetaceans view their world.

Cetaceans use clicks to ‘see’ with sound, better than humans can see with their eyes, in a form of sophisticated sonar called echolocation. This involves emitting clicks from their noses, then listening for how the vocalisations echo off their surroundings. The clicks are strong enough to pierce through sand and flesh, giving the animals a threedimensional picture (a hologram) of everything around them, from the inside out.

“Jane Goodall didn’t study apes from a plane. And so you can’t expect to study the ocean from a classroom. You’ve got to get in there. You’ve got to get wet.”

Fabrice Schnöller

Although cetacean clicks sound unremarkable to the human ear – something like the tack-tacktack of a few dozen typewriters – they are incredibly nuanced and organised. Scientists have discovered that sperm whales transmit these clicks at very specific and distinct frequencies, and can replicate them down to the exact millisecond and frequency, over and over again. They can then control the millisecond-long intervals inside the clicks and reorganise them into different structures, in the same way a composer might revise a scale of notes in a piano concerto. But sperm whales can make elaborate revisions to their click patterns, then play them back in the space of a few thousandths of a second. Schnöller and his team believe the only reason for sperm whales to have such incredibly complex and organised vocalisations, is to use them in some form of communication.

Schnöller and other scientists believe that since sperm whales are already sending and receiving ‘holographic images’ through sounds, they can probably share these echolocation images with other cetaceans, the same way a human might overhear a phrase and repeat it to another person close by. The HD audio rig Schnöller brought to Sri Lanka is a prototype for a more sophisticated 23-speaker recording device DareWin will deploy in January 2016. This new recorder will capture the full spectrum, essentially the ‘holographic image’, inside the sperm whale clicks. A team of physicists and linguists has built specialised software systems and computers to decode the clicks and process the sounds into images that humans can view – enabling us to see what cetaceans are seeing. Later in 2016, DareWin will attempt to send holographic images back to the animals, beginning a visual conversation, the same way an ancient sailor and islanders might have drawn out stick figures in the sand.

We approached a group of around 10 whales that were socialising, which can be seen in this picture. We were 40 metres away from them and we quickly understood that something unusual was unfolding. They were moving more quickly than usual – we got closer. Then I saw that there was some matter in the water – at first I thought it was plankton, which would not be unusual. But then I saw a tiny sperm whale and it suddenly became apparent to me: a birth had just taken place. This event has never before been observed.

I know what you’re thinking. Schnöller is a New Age dreamer on a fool’s errand to prove an impossible hypothesis. I thought the same thing when I first met him three years ago on Reunion Island, a French outpost 400 miles east of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean.

I had been sent to Reunion to write about a recent rash of shark attacks that had devastated the island’s tourist industry. Schnöller, who was then 42, was working on a shark-tracking system that would alert officials via a smartphone app when sharks were in the area. In his free hours, Schnöller mentioned he was studying cetacean communication.

He brought me into his office, a cavern of books and paper stacks in the upstairs of his wife’s health food restaurant, and showed me some footage of himself and some friends, freediving face to face with sperm whales. The images were haunting, stunning and strangely emotional. Schnöller mentioned he had dozens of hours of footage. He told me, in his thick French-accented English, that his next goal was to record communication clicks and perhaps one day talk to these animals.

Witnessing the birth was incredible, but I also realised I might be in great danger: when animals have given birth they will likely attack any potential predators who are as close as I was. However, whales are so intelligent – they knew I was not a danger to them.

Schnöller hadn’t always been interested in sperm whales. In fact, he’d known nothing about the animals before a sailing trip to neighbouring Mauritius in 2006, captaining a 60-foot sloop called the ‘Annabelle’ that a friend had just bought from Paloma Picasso, daughter of the painter. As the ship approached the coast, Schnöller and the crew noticed columns of steam shooting like geysers on the starboard side. The eruptions multiplied and drew closer until they surrounded the hull. The crew had heard there were whales in this stretch of the Indian Ocean: seeing them at a distance was common, but sailing into them was unheard-of.

Schnöller, who at the time only occasionally swam in the open ocean, went below deck to grab a mask, fins, snorkel and waterproof camera, then jumped in. The ocean is usually silent, but the waters around the Annabelle were thundering with an incessant click-click-click, as if a thousand stove lighters were triggering over and over again. Schnöller figured the noise must have been coming from some mechanism on the ship. He swam farther away, but the clicking only got louder. He’d never heard a sound like this before and had no idea where it was coming from. Then he looked down.

A pod of sperm whales, their bodies oriented vertically, like obelisks, surrounded Schnöller on all sides and stared up with wide eyes. They swam toward the surface, clicking louder and louder as they approached. They gathered around him and rubbed against him, face to face. Schnöller could feel the clicks penetrating his flesh and vibrating through his bones, his chest cavity.

Eventually, the mother brought the newborn to meet all the other whales and after a while, with me watching from the side, she pushed her baby towards me. This image here, on the right, is what we were looking at: the baby with the umbilical chord still attached and the proud mother behind. It’s a unique picture and a unique moment.

“I felt like I was contacting ET, you know, like this was communication from another planet,” Schnöller told me, sipping a Coke in his cluttered office. He spent two hours swimming with the whales that day. He’d known nothing about whales before the encounter. Afterwards, they became his obsession.

He sold his lumber supply business, drained his savings, and dedicated himself full-time to repeating the sperm whale encounter. He studied their physiology and discovered that they are, quite possibly, the most intelligent animals on the planet.

The sperm whale boasts a brain five times the size of the human brain, the largest ever known to have existed on Earth. Their neocortex, which governs higher-level functions in humans, such as conscious thought, future planning and language, is estimated to be about six times larger than in the human brain. Sperm whales also have spindle cells, the long and highly developed brain structures that neurologists associate with speech and feelings of compassion, love, suffering and intuition – those things that make humans human. In fact, sperm whales not only have spindle cells, but they have them in far greater concentration than we do.

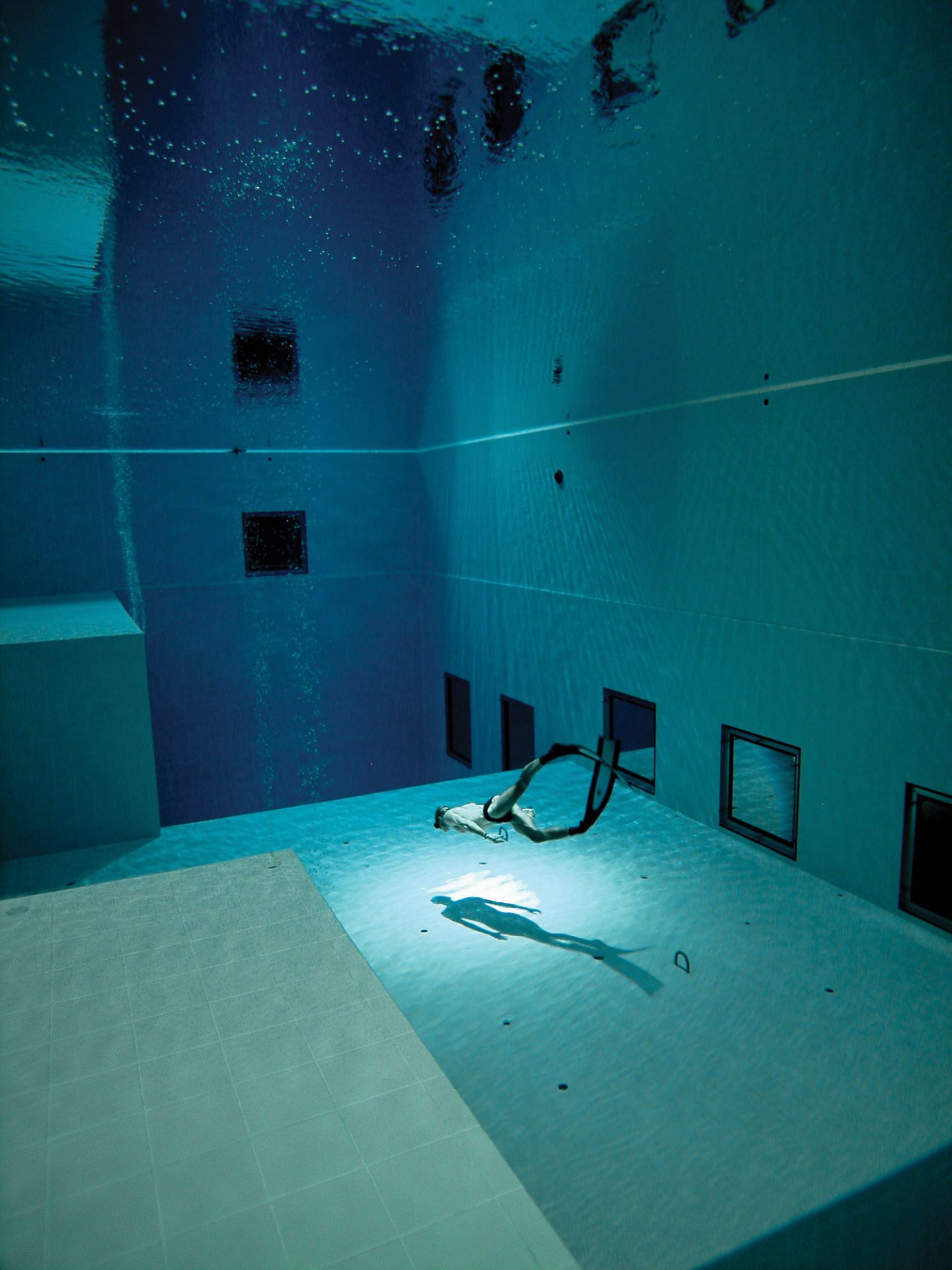

All my images are taken during freediving on one single breath of air. No breathing aids are ever used. All the images are taken in available light in order to give the closest possible testimony of the scene.

Brains take up a tremendous amount of energy. Animals don’t develop oversize neocortex and spindle cells by accident. They develop them because they use them.

Humans have had our current size brain for 200,000 years; sperm whales have had theirs for 50 million years. In the realm of brain evolution, 50 million years is a very long time. “Why do they have such huge brains? Why are these patterns so consistent and perfectly organised, if they aren’t some kind of communication?” Schnöller asked rhetorically. He mentioned that sperm whales have more brain mass and brain cells controlling language than humans do. “I know, I know, this is all just theory. But still, when you think about it, it just doesn’t make sense otherwise.”

Before Schnöller and DareWin, nobody could get close enough to sperm whales to study their communication. Although these animals are the world’s largest predators, boasting eight-inch long teeth and growing more than 60 feet in length, they are notoriously shy. They avoid submarines, robots and boats. The disruptive gurgle of scuba spooks them. During his life-changing experience in Mauritius, Schnöller discovered that when we approach sperm whales in our natural, human form – when we freedive with them – something amazing happens: instead of swimming away, the animals swim towards us, welcoming us into their pods for hours, and peppering us with their communication clicks, trying to make contact.

Humans share more than just language with sperm whales; we also share a number of amphibious reflexes, something scientists call The Master Switch of Life. The second water touches our faces, our bodies undergo an extraordinary transformation. Our heart rates lower to a third of our resting rates, blood engorges the internal organs, our lungs fill up with plasma. These reflexes protect us from the crushing underwater pressures that would otherwise kill or injure us on land. As we dive deeper, these reflexes become more pronounced, turning us into deep-diving animals. They allow us to plummet to incredible depths – far beyond what scientists believe is possible.

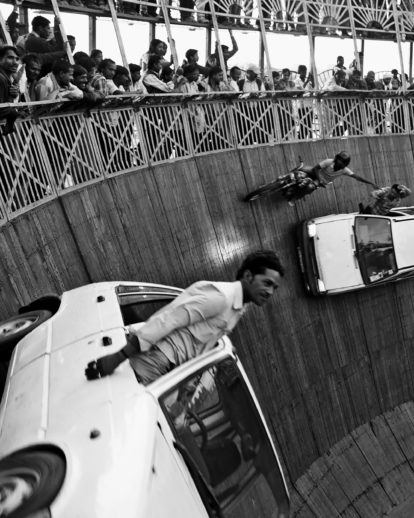

Artificial freediving facilities help us to prepare for deep natural freediving in the sea and it’s important to always reiterate to students that you must never freedive on your own.

Freedivers have recorded heart rates, at extreme depths, as low as seven beats per minute – about a tenth of the rate of someone in a coma and the lowest heart rate ever recorded. According to physiologists, a heart rate this low cannot support consciousness. And yet deep in the ocean it does, and still nobody quite understands how.

We’ve been using these incredible amphibious abilities for tens of thousands of years to harvest food, pearls and coral from the deep ocean floor. Written accounts of freedivers date to 2500 BC and span the Pacific, Atlantic and Indian Oceans. Around 700 BC, Homer wrote of divers who latched themselves to heavy rocks and plunged below 100 feet to cut sponges from the seafloor. In the first century BC, trade between the Mediterranean coast and Asia exploded, in part because of red coral, a favourite cure-all in Chinese and Indian medicine. Most red coral grew at depths below a hundred feet and could be collected only by freediving. By the eighth century, Vikings in the North Sea were freediving beneath enemy ships and boring holes in their hulls to sink them.

Pearl divers flourished in the Caribbean, South Pacific, Persian Gulf and Asia for more than 3,000 years. Sailors throughout the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries reported seeing pearl divers plummet more than 150 feet and stay down for 15 minutes at a time.

Freedivers have recorded heart rates, at extreme depths, as low as seven beats per minute. According to physiologists, a heart rate this low cannot support consciousness.

And then: poof. Gone. By the twentieth century, pearl farming and new fishing technologies had made freediving obsolete. The human body’s amazing diving abilities and human knowledge of freediving began to disappear. Competitive freedivers have rediscovered our freediving ability and can now hold their breath for up to 12 minutes at a time, and dive several hundreds of feet below the surface. But pushing the human body to such depths can be lethal, and many competitive freedivers die every year. In August 2015, Natalia Molchanova, the world’s most decorated and famous competitive freediver, disappeared off the coast of Spain while attempting some deep dives with friends. It’s this kind of death-defying diving that gives the recreational sport a bad reputation and has also scared marine scientists from ever attempting it.

Until DareWin, nobody had ever used freediving for marine research. No institutional researcher knew how to freedive, and few would ever risk their lives swimming face to face with 60-foot-long predators. But Schnöller and the rest of his DareWin team started doing it all the time. Since 2010, the team has travelled around the world on more than 10 expeditions documenting his encounters and recording echolocation clicks. With this unorthodox approach, DareWin has collected more communication and behaviour data on sperm whales and dolphins in five years than anyone – any institution, any university or oceanographic research team – in history.

“Jane Goodall didn’t study apes from a plane,” said Schnöller. “And so you can’t expect to study the ocean and its animals from a classroom. You’ve got to get in there. You’ve got to get wet.”

Back in Sri Lanka, the sperm whale mother and calf pass just a few feet beneath Schnöller’s fins. From this vantage, they look less like animals and more like submerged landmasses. The clicks they are shooting at us sound and feel like jackhammers on pavement. The whales are scanning our exteriors and peering into our bodies, our organs, heads and muscles. Schnöller and I stay perfectly still. We let the animals scan our bodies from our heads to our toes.

It’s a jarring experience to be so utterly vulnerable to instant death. And neither of us are adrenaline junkies. We hate extreme sports. And yet, for some reason, we both feel compelled to approach these enormous animals head on. Even though the whales exhibit no signs of outward aggression, I can’t help thinking that at any moment I could be swallowed up by their 12-foot-long mouths and chewed up in their sausage-like teeth. I’m trusting these animals with my life with nothing more than a feeling, some innate sense within me that tells me that although humans have hunted these animals to the brink of extinction over the past 200 years, these whales before us don’t want retribution. They’ve approached in peace and the least I can do is respect this moment, kick my fins a little deeper, and open myself to this encounter.

Then, suddenly, the mother and calf languorously veer left, and prepare to dive deep. And just in time, I’m almost completely out of breath.

I start kicking towards the aluminium sheen of the surface, looking down as the two whales grow smaller and smaller until each disappears into the shadows like airplanes disappearing in a dusk sky. The once-thunderous clicks soften and fade, and the ocean is, yet again, silent.

Small excerpts from this article originally appeared in James Nestor’s 2014 book, Deep.