In April 2011, American photographer Michael Christopher Brown was embedded with rebel soldiers in the Libyan city of Misrata when he was hit by a mortar round. The revolution against the 42-year rule of Muammar Gaddafi was Brown’s first experience of conflict and, in Misrata, only two months into the revolution, he would find himself caught up in some of the fiercest fighting of the war – the front line shifting constantly from street to street, riddled by sniper fire and shelled indiscriminately by pro-Gaddafi forces.

As he was rushed to hospital, falling in and out of consciousness and bleeding heavily from his chest, shoulder and arm, Brown would experience first-hand the grim reality of war. He had lost almost half the blood in his body and needed two transfusions, but would survive; his friends and fellow photographers Tim Hetherington and Chris Hondros, who were also caught in the blast, did not. It was one of the darkest hours for photojournalism.

The Libyan conflict was a crucially formative experience for Brown. During the eight months that he spent in the country – following the rebels from city to city until eventually, reaching Sirte, he witnessed the capture and killing of Gaddafi – Brown began to develop a new approach to his work, eschewing a traditional journalistic objectivity in an attempt to come to terms with the conflict that he was witnessing.

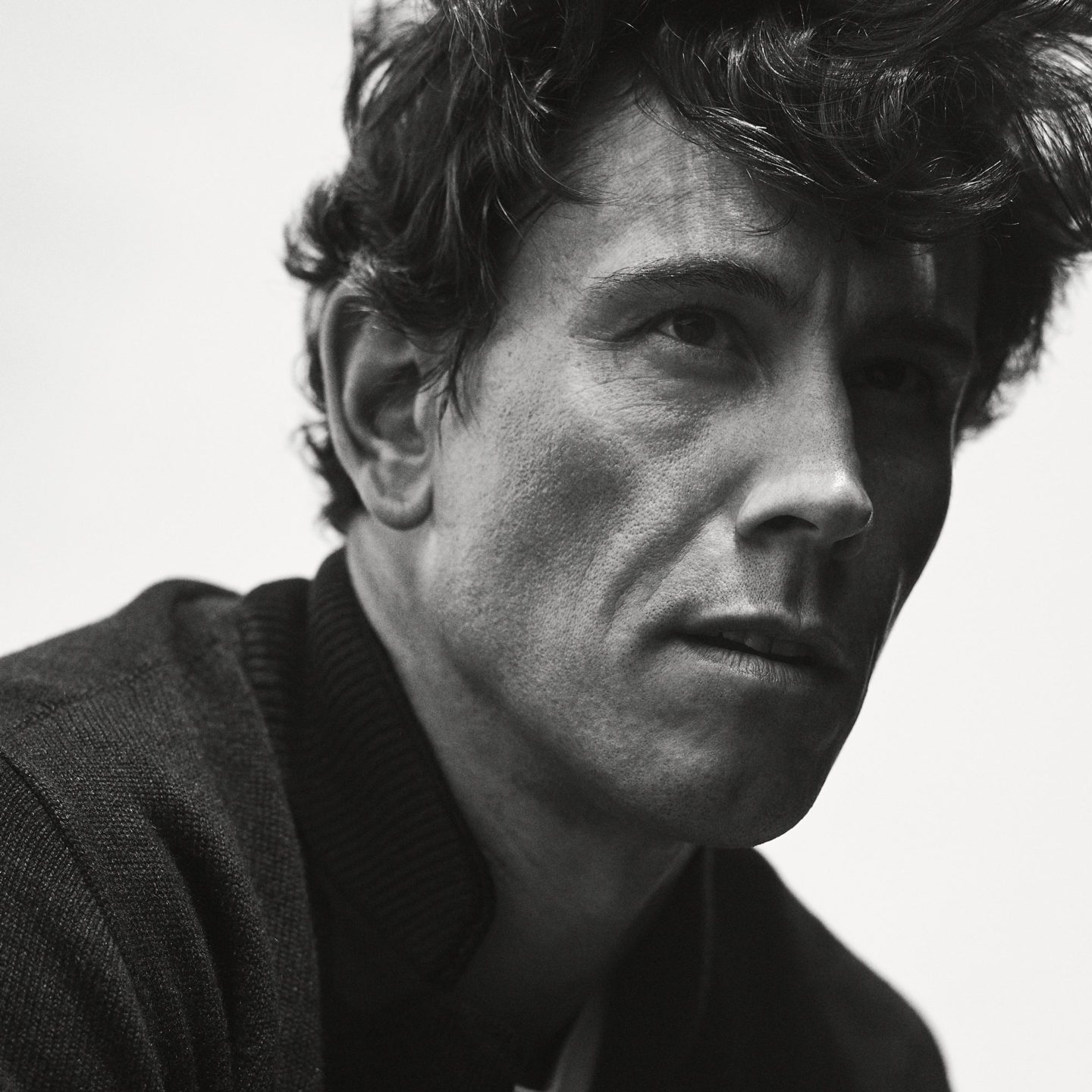

Jacket by Aspesi, T-shirt by A.P.C., trousers by AMI and shoes by Nike.

“For about 12 years I had been working on commissions and projects, but I never really knew why I was doing them,” he tells me. “It was only in Libya that I began to realise who I was as a photographer. Since then I’ve been recognising the role I have in the story, developing a vision that I found there.” It was this realisation – that he should not only document the war but his experience of it as well – that has formed an intimate and engaging portrait of the conflict, and marks Brown as one of the most innovative documentary photographers working today.

I meet Brown in London. He’s in town for the annual general meeting of Magnum Photos – the illustrious photographic cooperative founded in 1947 by Henri-Cartier Bresson and Robert Capa, to which he was nominated in 2013. We sit by a quiet part of the Thames, looking across the river to the traffic on the embankment. He speaks slowly and carefully and without disfluencies, his voice only ever faltering, almost imperceptibly, at the mention of Hetherington and Hondros. I ask questions about Libya and how the reality of conflict differed from his expectations and, as he pauses to consider his answers, staring, brow slightly furrowed, into the murky indifferent water, I wonder how it is possible to sit here, still and calm, having experienced such visceral and bloody conflict.

“I had these ideas about what it would be like before I went,” he says. “I had watched TV shows and read the news, and met people who had been, but then you get there and you witness such extremes of human experience. There’s always so much more happening around the scene. One moment it can be just like this,” he gestures at the traffic across the river. “Then a few blocks away there’s smoke and sounds, and you know that’s where the fighting is. That really played with my mind.”

MICHAEL wears jacket and T-shirt by A.P.C.

A week after he arrived in Libya, Brown broke his camera and instead started using his iPhone, processing his photographs through the Hipstamatic app. He was only able to capture one frame every 15 seconds, and it would often crash, deleting his work, but he quickly discovered his phone could be a considerable asset.

With smartphones ubiquitous in a revolution organised through social media, Brown was no longer identifiable as a photographer, as an external observer, and could experience the action from within the crowd. “People don’t see the phone as a professional piece of equipment,” he explains. “It’s less threatening; they approach you in a different way.” The intimate access he gained as a result, standing shoulder to shoulder with the rebel fighters, gave him a unique perspective on the war, but it also raises questions over how documentary photographers should operate in conflict zones.

I ask him whether it is possible to maintain an ethical distance; whether, when he is so involved with one side of the war, he can accurately record the events of the conflict. Brown is unequivocal: “For me the question is, ‘What is accurate?’ Photography can be very subjective, and as a photographer you’re constantly making decisions about what to include or not include in a frame. In Libya there were numerous times when you would see the body of a government soldier and the revolutionaries would be celebrating, showing me these peace signs with their hands. Sometimes I would try and crop them out of my frame – perhaps it was only happening because I was there – but at the same time I have a presence. Does that mean I should include it in my frame or pretend it’s not there?”

It was through experiences like this that Brown realised the only way to accurately present the war would be to shoot it as he was experiencing it: the brutality of war, the charred bodies and child soldiers – as well as the mundane, laughing with his colleagues as they prepared to sleep, or the lion abandoned in the Tripoli zoo.

It was a decision that would come to define his experience throughout the rest of the war and culminated in a book, Libyan Sugar, published in 2014. Much has been made of the book’s graphic, unflinching representation of the revolution, but it is equally notable for the juxtaposition Brown makes between the scenes that he saw unfold in front of him and the anxious emails and Skype conversations with his family back in Washington state.

“People don’t see the phone as a professional piece of equipment. It’s less threatening; they approach you in a different way.”

Michael Christopher Brown

More than just a record of the Libyan conflict over eight months (though, as Brown points out, it could be used as such), Libyan Sugar is an intimate diary, forming a personal vignette that is far more engaging, and captures the events of the revolution with a greater honesty, than the ostensibly impartial images that illustrate news reports. Presented without captions, you discover the conflict as Brown did – trying to piece together images and experiences in an attempt to understand what was happening, only to realise that the closer you get to the confusing, disorientating war, the more difficult it is to comprehend.

Brown was raised in the Skagit Valley, a small farming community close to the Canadian border and the Pacific Ocean. It was there, in the tranquillity of the rural north-west, that he would be introduced to photography by his father – an ear, nose and throat surgeon – who kept a small black-and-white darkroom. His father would leave Polaroids taken during surgery lying around the house and Brown cites his early exposure to these graphic images as an immunisation against the mutilation and bloodshed he would witness in Libya and other conflict zones.

After obtaining a master’s degree in documentary photography in 2003, he worked on domestic projects, interning at the State Journal Register and National Geographic. But it was the inspiration he found in New York, living in an 11-storey warehouse building called the Kibbutz in Brooklyn, that sparked his interest in going to war. With intimate access to the work of conflict photographers Stanley Greene, Kadir van Lohuizen and David Alan Harvey, as well as Tim Hetherington, Brown developed the curiosity for conflict, so alien from his peaceful upbringing in Washington state, that would eventually lead to Libya.

MICHAEL wears jacket by Officine Generale and jumper by Berluti

Brown defies easy classification. Despite producing his most celebrated work during the Libyan and Congolese conflicts, he is not a war photographer. Nor can he be described as a photojournalist, though, as he tells me, he takes care to record events, places and names accurately; in Libya, Brown found the neutral approach of a photojournalist hampered his ability to capture the complex, dynamic conflict he was experiencing. Rather he is simply a photographer, using the camera as a way to try to understand and make sense of the confusing and complex world that we live in.

Later, as we’re walking back along the river, I ask him if he would ever return to Libya. As with all my questions he pauses and considers his answer, before saying with typical honesty and humility: “With these projects it’s hard to say I do it for the people, because I don’t. I do it for myself and if I go back it is because I am curious, I want to find out more. The news reports talk of saving the world and it’s a very humanistic idea, it’s a great pursuit, but it’s rare that you can do that. Instead it’s important to do something you love, because that passion shines through your work. There’s something useful in that; people will understand it.”