The Old City in Tripoli, Lebanon, is one of the most impressive demonstrations of Mamluk architecture in the world. Its medieval souks and mosques have inspired effusive reactions in everything from fourteenth century travelogues to twenty-first century websites. Yet just thirty minutes away there’s a sense of a very different age and civilisation, as giant space-like concrete structures loom against Lebanese skies. Local Tripolitans I meet tell me that they imagined them as alien ships descended from the heavens when they were younger. The truth, though more prosaic, is no less intriguing.

The structures are part of an abandoned modernist exhibition ground complete with futuristic concrete ticket booths, concert halls and theatres. It was built in the Sixties, a time when Lebanon was asserting its position as the jewel in the Arab region. The intention was for it to host exhibitions that would attract international audiences and artists, establishing Lebanon as a key regional leader in cultural events. Such global ambition demanded an architect with a reputation to match, and the Brazilian Oscar Niemeyer – then living in exile from his country’s military dictatorship – fitted the role perfectly.

This structure at the Maarad Rachid Karami International Fair was intended to be a helipad that would lead into a space museum.

The Maarad Rachid Karami International Fair would go on to consist of 15 large structures sprawled over a massive site, including an open-air stage, a space museum, and a dome. Yet today, despite the notoriety of other Niemeyer projects – not least Brasilia, on which the fairground is partly modelled – the site lies largely unknown outside of Lebanon. Though construction began in the Sixties, the Maarad would never reach its completion or fulfil its true purpose. I talk to Wassim Naghi, President of Architects for the Order of Engineers and Architects in North Lebanon, who is heading up the fight for its restoration. ‘It was like the night before the wedding,’ he declares. ‘Everything was ready and then it turned to complete tragedy.’

As the spring of 1975 approached, the wedding seemed very much on course. Chandeliers glistened, marble tops shone, and all the furnishings had been set up in preparation for the grand opening of Lebanon’s first international exhibition. Then, on a crisp April morning, cracks of gunfire bounced and echoed across the concrete walls. The Lebanese civil war had started.

A skylight in the proposed open air exhibition space. Designed in line with Niemeyer's inspiration by the female form.

Built to exhibit the beauty of artistic works around the region, the site instead became an improbable location for a military base. Local militia ransacked the place, looting marble tabletops, lighting fixtures, doors, chairs, taking anything and everything. Soon, the neighbouring Syrian Army entered the conflict, occupying areas that included Tripoli where they descended on the Maarad and established a base. Their troops would not leave Lebanese soil till 2005, following the assassination of former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafic Hariri.

Step inside the site today and you are immediately greeted with an expanse of seemingly endless concrete. One million square metres of it to be exact. To the right, a giant arch soars overhead; close by is a circus tent-like dome. It’s classic Niemeyer. To the left, a long exhibition hall extends seemingly limitlessly to the horizon. What’s most striking is the way Niemeyer stokes intrigue by playing on curiosity at its most childlike, enticing the visitor to explore every building through its distinctive shape and jaw-dropping scale.

The open air theatre.

Any architecture that marks itself on a city’s skyline will become an anchor for collective memory. For many Tripolitans, stories and recollections of the Maarad serve as a physical and psychological landmark of happier times, and of the larger frustrations often felt by countries recovering from internal upheaval. Naghi’s own career as an architect traces its beginnings to when he was a child staring with curiosity from his balcony at the large shapes in front of his house. For Sahar Minkara, memories of running her fingers as a child along the smooth curved concrete shapes and seeing images scrawled onto the walls by the Syrian soldiers would inspire her later work as an interior designer. For Mira Minkara, the giant structures standing in isolation stoked a fascination with ruins that would move her to run tours in Tripoli and across Lebanon. Each described to me their perceptions of how Tripoli had changed, both during the conflict and the period of recovery afterwards, through their shared memories of the Maarad.

‘I remember a whole herd of cows being kept inside the experimental theatre, and clothes hanging off lines in the ticket halls.’

Sahar Minkara

Naghi’s career as an architect came full circle when he was asked to help redevelop the Maraad. ‘I was born there,’ he told me, pointing to a beige building sitting directly opposite the gates on the site’s perimeter. ‘Back then, we used to cross the dirt to the site which was filled with little yellow wildflowers. When I was about ten years old we used to wander down and climb on top of the building materials just to check out what these huge Lego-style structures were.’

At first the Syrian soldiers would only allow military personnel through; tanks, transport vehicles, food supplies, five-star generals. But they became increasingly alive to the inquisitive gazes of children peering through the iron bars of the perimeter fence. As time passed, the soldiers caved in to the children’s entreaties, allowing them into carefully selected areas.

Exiting the giant shell-shaped experimental theatre.

‘Our main target was always the experimental theatre with its sloping roof,’ Naghi recalls. ‘It was a little bit dangerous, but when you put on proper shoes, you are fine. We used to race to the top and slide all the way down.’ It was a rite-of-passage for many Tripolitan children that continues today. Naghi laughs, ‘My mother used to tell me off when we’d come back home with bare arses from torn jeans’.

The fact that it was forbidden only added to the enchantment of the site for the kids who would glimpse everyday scenes of the comings and goings of soldiers living there. ‘I remember a whole herd of cows being kept inside the experimental theatre,’ says Sahar. ‘[There were also] clothes hanging off lines in the ticket halls and graffiti scrawled on the walls saying, “Assad forever”.’

The Maarad serves as a rare oasis amid the concrete sprawl of the ever-encroaching city. ‘If it wasn’t for this space, it would have just become more buildings,’ says Minkara. Public areas like this are often limited or contested in cities in Lebanon. She remembers long carefree summer nights from her youth. One time there was a Russian ballet performance, another time the Lebanese band, Soap Kills, stirred the crowd with the sultry tones of lead-singer Yasmine Hamdan. In the earlier days, the wind was said to carry the scent of lemon and orange blossom from the trees for which Tripoli was renowned. Sahar recalls how the Maarad was the rendezvous spot for young lovers. ‘There was a lot of flirting, sitting with boyfriends in cars, and first kisses that happened there,’ all under the embracing cover of the trees.

The turtle-shell-like shape of the experimental theatre makes it one of the most distinctive buildings on the site. Countless children have performed acrobatics on its sloping roof, but the concrete ‘tent’ forming the shell of the dome is itself ‘an acrobatic structure,’ explains Naghi. It’s a 40cm-thick concrete base sitting atop a 62-metre ring underground on neoprene pads. These enable the structure to withstand movement from the soil due to flooding, seismic activity (Lebanon lies on a fault line), extreme temperatures, or even the unanticipated mortar rounds during the war.

It remains the only round theatre in the region and was initially designed to include a hydraulic stage that would rise and rotate during the performance. One night, Naghi drove his Land Rover down to the theatre, opening the door so his sound system could blare out Pink Floyd guitar solos. The building’s curved structure amplified the soundwaves, in effect becoming a giant speaker. He will never forget the wailing cries of the guitar reverberating endlessly throughout the structure and across the deserted fairground.

Niemeyer’s architecture characteristically avoided sharp corners and angles. Instead, explains Minkara, there are a lot of curves. Niemeyer’s architecture was infamously inspired by the female figure. ‘My work is not about form follows function’, he would quip, but ‘form follows feminine’. It’s an aesthetic theory that might raise eyebrows today, but gender politics aside, what’s striking is the feeling of energy on this site, despite its being essentially abandoned. ‘You feel as if the space is suspended in time and yet, somehow still alive. It was a great source of inspiration for my work today as an interior designer,’ says Sahar.

An abandoned ticket booth for the open air theatre.

Back on the site, Naghi gestures to the grande couverture, the covering adjacent to the vast futuristic exhibition hall. He recounts how the Syrian army stored tanks, artillery, and munitions under there. ‘Access was totally forbidden,’ he recalls. ‘It’s very rare to find photos of that part of the site between 1975-95. This means that for 20 years this aspect of the Maarad’s history was largely undocumented. People were put off from seeing the area because of the bad memories associated here. Some were kidnapped, taken for investigation, tortured…there are a lot of stories about that sort of thing happening here.’

Many Tripolitans who were adults during the war associate the space with the Syrian occupation when friends and relatives were tortured there. ‘I still can’t get certain scenes out of my head. Like hiding inside the toilets, in the corridor, away from the sounds of shooting, bombings, and the fear. Later, in the mid Seventies, we were more hardened to the war and would come here to hang out. Our main concern though, was to survive,’ says Naghi.

The hold underground was supposed to include ticket booths for the car park as Niemeyer favoured unobstructed views, creating an illusory sense of infinite space.

When you look at it on a map, the Maarad is instantly recognisable. Located between the seaside town of Mina and Tripoli’s Old City – sitting to the left – it looks a little bit like a lung. There’s nothing random about its location. Niemeyer selected it from multiple options. Tripoli (meaning ‘three cities’) was first given its name by the Romans – though the etymology is Greek. In response, Niemeyer chose this site because it lay at a roughly equal distance from the coastal town of Mina and the old city of Tripoli, allowing it to become part of an urban triangle.

What couldn’t be predicted was how the conflict would knock the breath out of the Maarad, leaving just bare concrete structures standing like hollow bones, empty but largely intact. It was no small irony that, as Naghi explains, its futuristic design worked perfectly in terms of turning it into a military base. ‘You’re on a site of one million square metres,’ he says, ‘with thick concrete tunnels, underground facilities and five shelters.’ These shelters, embedded underground with 1.5 metres of soil on top, were built as part of the fair because, during the Sixties, it was a requirement – because of regional hostilities – that public spaces should be equipped in this way.

‘I still can’t get certain scenes out of my head. Hiding in the toilets, away from the sounds of bombing. Later, we were more hardened to the war and would come here to hang out.’

Wassim Naghi

Minkara calls the Maarad the modern ruins of Tripoli. ‘I’m fascinated by ruins in general,’ she says. ‘This space bears testimony to Lebanon’s golden era, because whilst much of the region wasn’t very avant-garde, here we were commissioning the best architect in the world to do this huge project.’

For ‘the best architect in the world’ it would be the final project during his exile. In France he had already designed the French Communist Party’s headquarters. He wanted his politics to be enshrined too in the Maarad through the large communal housing project he had envisioned for the site.

Terrified of flying, Niemeyer had first arrived in Lebanon by boat. The journey took weeks, much to the dismay of gallery owners and fans who wanted to greet him personally and waited patiently at the airport only to be told he would be arriving weeks later, at the sea port, not the airport. When he eventually arrived in 1962 he spent a month surveying the site and travelling up and down the country to understand it. One particular example of how he integrated local architecture can be seen in one of the main exhibition halls featuring tall pointed arches, a traditional feature in Lebanese architecture but a departure from his usual style. After learning the lessons from his past projects in Brasilia and other locations, ‘this was Niemeyer in his prime,’ says Naghi.

A dead rat inside an underground escape tunnel, built as a requirement for public spaces in the 60's in Lebanon given the regional conflicts at the time.

Detail from the open air theatre.

Yet when the civil war in Lebanon finally ceased in 1990 and a decision was made to complete the Maarad, Niemeyer’s phone never rang. To call back the original designer – ‘these are considered basic ethics in architecture. It was a huge insult,’ says Naghi. Niemeyer harboured the grudge that the Lebanese government hadn’t consulted him right up till his death in 2012. By that point, Naghi had been invited to be the architect in residence for the reconstruction of the Maarad for the Beirut construction firm, Dar al Handasah.

He felt straight away that the plans were a transgression of Niemeyer’s original intentions. ‘They were in a rush to host an international Arab event and I felt I couldn’t stop the project or change it and did not want to be a part of this crime – so I immediately resigned,’ he tells me. His frustration at the compromised project combined with Lebanon facing an economic recession drove him to work in Abu Dhabi, not returning to Lebanon till 2004.

Many Tripolitans cite this flouting of sensitivities in the redevelopment as being representative of broader problems with a government focused on short term goals. Chief among these is a readiness to privatise reconstruction projects at a whim, rather than having a cohesive national plan. Such a blatant disregard for fairness and equality stands in contrast to the situation under the 1958-1964 presidency of Fuad Chehab – still strongly respected for his socially-aware reforms – in which major development projects had to be distributed equally throughout different regions as part of a decentralisation policy to stimulate local economies. The decision to place the Maarad up North was just one consequence of this.

Pointed arches feature in Niemeyer's design, a departure from his traditional curved arch style which can be seen in the background.

The campaign today to do the site justice has led to the perhaps unsurprising awareness, that older generation Tripolitans have always struggled with their relationship with the Maarad. When Minkara did a survey of their emotional response, she found that, ‘it doesn’t belong to their memory of the city because it was inaccessible to them whilst being used as a military base for years’. This is precisely why Naghi established the Niemeyer Heritage Trust to help preserve and raise awareness of the site. ‘Initiatives have always paved the way for effective progress in post war Lebanon,c he declares.

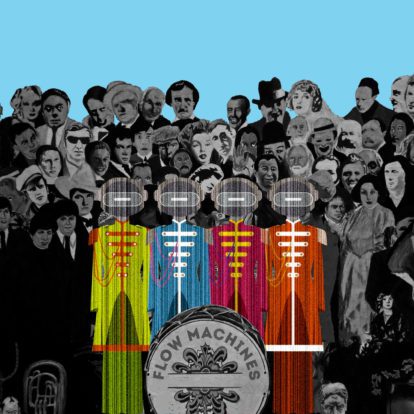

In 2014 the Trust launched a competition on how the Maarad might be redeveloped. The initiative produced over 350 ideas and subsequently reached the final stage of the South African International Union of Architects Exhibition. This proved fantastic exposure, since many of the architects who saw it were – despite their inevitable familiarity with Niemeyer’s works – unaware of the Maarad Rachid Karami International Fair’s existence. The following year, Naghi invited the Brazilian ambassador to the fair. This led to the official twinning between Brasilia and Tripoli which is now underway.

A Brazilian-style villa inside the fair built to house the architect and VIPs. The site was vandalised by the Syrian Army and never completed.

A small pyramid, built for the children's play area.

Progress is also being made with UNESCO, who listed the Maarad last year on its list of potential world heritage sites. But Naghi warns that this requires much more work from the Lebanese government to make it happen. For a start, the site will require millions of dollars to restore and maintain the existing structures which are in imminent danger of collapse. While many have fond memories of the Maarad, there is a problem that many are unaware of the cultural value it holds as well as the potential importance it plays in serving as a public area.

And while the wait for restoration continues, there are other forces to contend with that transcend both politics and personal agendas. As we talk, I can see that beside Naghi’s feet little yellow wildflowers are triumphantly pushing through hairline fractures in the concrete, steadily reclaiming the space that was once their own.