On Tuesday morning, outside of New York’s Penn Station, Jason Everman is more likely to be pegged as a hanger-on from the previous night than a man inscribed in the annals of rock and roll history. With his brownish, curly hair tied up in a rounded bun and arms adorned with leather bracelets and necklaces as well as blue-skinned deities and runic lettering, he could’ve been someone’s Bay Area uncle on a holiday vacation. The image is completed by his heather grey t-shirt, which features a weaponised cartoon ape with the words, ‘You've Been a Very Bad Monkey’.

He has a habit, too, of not being very forthcoming with his past. Take the 2014 lecture, for example, where he said that he spent his early adult life touring as ‘a professional rock musician’. This fuzzy statement about getting paid to rock appears on his Tillman Scholar biography, too. But these generalisations leave out revelations like how Everman was an early member of Nirvana. Or how after getting fired from Nirvana, he then went on to become a member of Soundgarden. ‘I was a professional rock’n’roll musician, which in retrospect still seems kind of funny,’ he says.

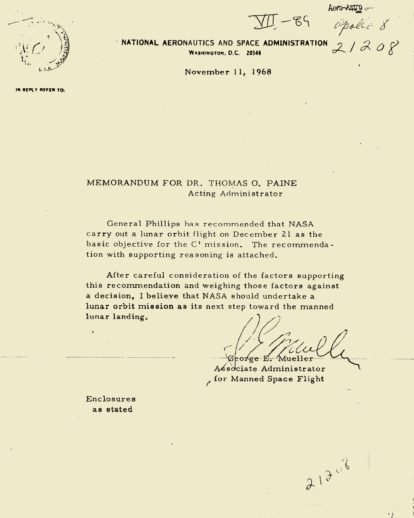

Jason Everman shot by Vincent Tullo in East Williamsburg, New York, 21 August 2018.

It’s something Everman’s newer acquaintances back home in Washington have found themselves hard pressed to resist asking until they’re buzzed and loose. And when they do, he doesn’t dwell on the subject for long.

‘He didn’t miss a beat,’ Shawn Mitchell, the manager at Everman’s local Oyster shack, Hama Hama Oyster Saloon, says when he recounts delving into the former musician’s past around a bonfire.

It might be because just as Everman was beginning to taste the perks of rock star fame, he was axed from both bands. But instead of becoming a semi-tragic case of Pete Best or Scott Raynor, Everman enlisted in the special operations forces, and then went on to study philosophy and history. These days, he’s continuing his studies of the human condition. Or at least, that’s one way to describe sailing around the world, courting an apprenticeship with Patagonian chef-qua-fire whisperer Francis Mallmann, and living out the rest of your days in Buenos Aires running a bar.

* * *

After failing to find a decent sushi spot in Chelsea that’s open before lunch, we settle into wooden window seats at Chelsea Square Restaurant. We’re beneath the gaze of the blue aliens from Avatar and a somewhat over-dedicated waiter who describes half a dozen vegetable sides and salad dressing to accompany the grilled tuna special.

When asked whether or not he could say that punk rock saved his life, the answer is not straightforward. Still somewhat fresh from academia — a philosophy degree from Columbia University, followed by a year studying military history at Norwich University in Vermont — Everman often speaks in a logic-based manner. Each sentence on — say — the connection between human essence and warfare, or his rationale behind ordering a platter of grilled tuna is dovetailed by the previous one. Throughout he considers counterfactuals, continually qualifying his statements.

‘If it wasn’t punk rock, it probably would’ve been something else,’ Everman eventually confirms. ‘It definitely gave me purpose and I derived joy from it. It got me engaged, and I guess to this day, my beacon in life is to stay engaged.’

Everman (left) with Kurt Cobain, Krist Novoselic and Chad Channing of Nirvana in 1989. Photography: Ian Tilton.

Everman was born in the Alaskan wild. Before his birth, Everman’s parents, Dianne and Jerry, whom he described as ‘granola, live with nature kind of hippies’, wanted to return to nature and moved into a cabin in Ouzinkie, Alaska.

Within a few years, the isolation quickly overwhelmed Dianne. Not long after Everman was born, she bolted with her toddler to Washington, eventually getting remarried to a former Navy serviceman, giving birth to Everman’s half-sister, Mimi, and settling in the Poulsbo area of the Puget Sound.

As a teenager, Everman was a gawky string bean with a discipline issue. He and his friends would climb electric towers in the fields, egging each other on to see who would get the closest. In junior high, Everman and a classmate blew up a school bathroom toilet with an M-80. The teen created so much havoc that, by the time he was 17, his mother shipped him up to Alaska, where he met his biological father and worked aboard his commercial fishing boat for the summer, sorting through the daily catch and making repairs to the ship. He loved it and returned for the following three seasons.

‘I graduated high school early, and that same week I was on a plane back up to Alaska to work,’ he says.

It was during this period that punk’s universal siren-call for moody teenage youths made itself heard in young Everman’s life. At the time he was 15 and subsisting on a diet of technical shredding from KISS and Black Sabbath. Then he came across a mix cassette loaded with anthems from Zero Boys and the Sex Pistols’ Never Mind the Bollocks.

‘It was an instant visceral connection,’ Everman says. ‘Like, “I’m not sure what this is, but I like it. It’s making me feel something cool.”’

‘I was a professional rock’n’roll musician, which in retrospect still seems kind of funny. It’s kind of an odd thing to do, I think.’

Jason Everman

Soon a light bulb went off in his head. Even a chump like him could play Black Flag’s Nervous Breakdown. With his high school classmate Chad Channing, Everman played the guitar in a thrash-metal band called Stonecrow. Their paths eventually overlapped with two musicians in the Seattle scene named Kurt Cobain and Krist Novoselic. They recruited Channing to play the drums for their first album Bleach, and later, as per Channing’s recommendation, would loop in Everman as a second guitarist. The world would eventually know this collective as Nirvana.

‘Just the idea of making money and playing in a band was so alien, I didn’t know anyone who did that,’ he says. ‘Even playing outside Seattle seemed like a stretch.’

Everman gelled with Nirvana’s members at first, the collection’s depressive mood representative of the Seattle gloom. Having saved up around $20,000 from working in Alaska, he helped them pay off the recording fee for Bleach. Famously the cost was $600 – in return for his help he got a nominal second guitar credit on the album, but in an interview Kurt Cobain said he hadn’t played a single note on what was released. Though he did eventually get a place as the actual second guitarist to amplify Nirvana’s sound first at local college dorm parties, and later on its West Coast and 1989 US tours.

But cracks soon emerged. Everman, always covered by a dark cloud, clashed with Cobain, turning the journey into a miserable experience for all parties involved.

‘I think the root of my unhappiness in playing with that band was the realisation that I’d never be more than a second guitar player,’ Everman says. When the tour ended, so did his time with Nirvana.

‘My intent is to keep engaged with the world, with life, with whatever I’m doing, with the people in my life. The whole getting old thing is an adventure in itself.’

After getting the boot, Everman returned to his musician-commune apartment in Seattle to plan a backpacking trip across the Himalayas. But then the phone rang. Kim Thayil of the grunge band Soundgarden was on the line. The band’s founding bassist Hiro Yamamoto was quitting, and they needed a replacement for their upcoming Louder Than Love tour, fast. ‘We’re auditioning,’ he said. ‘You want in?’

Not only was Everman a Soundgarden superfan with an advance copy of the album, but the band had just signed with A&M records, a major label, and was on the verge of rock stardom. The opportunity meant per diems, hotels, and paying the bills — not debating whether or not to pay for food or gas and sharing a platter among bandmates from the salad bar as he had with Nirvana.

Everman quickly procured a bass and spent hours learning the lines for Power Trip and Loud Love from his advance copy. By the time he showed up to play with Thayil, Matt Cameron and Chris Cornell, the material felt instinctual.

‘He came to audition, and we spent the afternoon jamming,’ Thayil recalls. ‘We liked him.’

Despite Everman suddenly graduating to the big leagues of rock and roll touring, not every aspect of his routine reflected this. At the time his diet consisted of Subway’s tuna salad sandwiches and Mountain Dew Big Gulps. A surprisingly understated choice for a man whose signature move involved throwing his bass guitar across the stage, a lot.

Among his highly-strung victims were former Sex Pistols member Steve Jones’ guitars. ‘We thought he’d be cool with it: he’s Steve Jones!’ Thayil says. ‘We just said, like, “Sorry?”’

But despite joining his favourite band, the storm clouds continued to hang over Everman’s head, in a way that even a collective with lyrics like ‘I’m going to feed the prison, feed the prison/Color in with lakes of red/Pile of bones for my bed,’ couldn’t handle.

On stage with Soundgarden in 1992, Roskilde Festival, Denmark. Image: S. Green

‘Sometimes his moods would have him disassociate from the rest of us,’ Thayil says. ‘We were perfectly capable of handling that, but unfortunately it made it difficult to bond and gel as a unit and a team, which was something we really needed. It really shook us that we lost Hiro.’

Everman, unfortunately, wasn’t their solution. The band began to buckle and drift apart during the various legs of tour. So – to save Soundgarden – they dropped him.

‘It was rough,’ Everman says. ‘The best analogy I could make is getting dumped by a woman or a person you’re totally in love with. It was honestly that feeling, just raw. It just sucked.’

* * *

Strolling along the Highline in Chelsea, the conversation drifts from Everman’s life back in Washington, to the Wes Anderson movie The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou. He’s in love with the film, and there’s a special place in his heart for the titular character, a globetrotting bearded oceanographer with a slight paunch and a huge ego, portrayed by Bill Murray.

Everman considers himself to be a lot like Zissou. Both are adventurous vagabonds with a desire to see the world, and the pair look a lot alike. And both men are flawed individuals who never say die in their life story.

Shortly after Everman recovered from the breakup with Soundgarden, he moved to New York, hoping that relocating himself to a new coast would prove a catalyst for change. While slumming it in Alphabet City, Pat Dubar of the stoner-grunge outfit Mindfunk approached him to play rhythm guitar in the band, with a promised opportunity of carte blanche creative freedom in writing song material.

With his four new bandmates, Everman moved once again, this time to rural Monmouth County in New Jersey. In the following days, they experimented and wrote material for Dropped, Mindfunk’s second album. ‘If anything, it doesn’t suck. Like, I’m not ashamed of this,’ Everman says about the fuzzy, distortion-loaded record. ‘I’m like a lot of people, I’m my own worst critic. If I’m saying it doesn’t suck, it’s probably okay.’

After years of performing other musicians’ material, Everman had a piece of original music he could call his own. But he also saw the end of his career in sight. The band was factionalising, he says, with him and a few other band members moving out to San Francisco. He was entering ‘the year of sex, drugs and rock and roll,’ which would probably destroy him in the long run. And, as he toured and played festivals in Europe, he ‘started realising, at least playing live, that I was going through the motions.’

After leaving Nirvana and then Soundgarden, Everman worked as a bike messenger. New York, 1997. Image: A. Smithee.

Unbeknownst to his bandmates, and almost anyone who really knew Everman, the musician had grown up with a deep fascination and respect for the military. In junior high, he had pored over vignettes of soldiers during the Vietnam War from a book that Dianne had bought him, while her father, who rose to the rank of company commander during World War II, would recount to a young and wide-eyed Everman memories of D-Day and V-Day. He usually kept mum about these interests.

‘Being this punk rock kid in the 1980s, that whole thing was decidedly anti-military,’ he says, ‘but when I started examining my own feelings about it, it was “Do I think that because it’s part and parcel of belonging to this scene, or am I just being a parrot? Should I just think about this for myself?”

A video director Everman knew in Seattle who was a former Navy SEAL said enlisting was the best decision he ever made, and recruiters in the Bay Area said it would be possible to get him on track for the US Army Rangers. So Everman started secretly getting up early and exercising: biking, running, doing laps at the local YMCA. A month after finishing his touring commitments with Mindfunk for the 1993 US Tour, he was on a plane to Fort Benning, Georgia, where his head was shaved and he began his path to 75th Ranger regiment.

The months leading up to his selection for the rangers were brutal, Everman says, although he adds that ‘it ticked a lot of boxes I wanted to tick in terms of personal growth and development’. Even before his selection, he challenged himself to endure a lack of freedom during phases like basic training and ranger school.

‘You’re tired, you’re hungry, you’ve got the stress of like passing your patrol,’ Everman says. ‘It’s not combat — in a lot of ways combat is easier — but it is stressful.’

Everman taking part in US Rangers training, 1996. ‘War involves a lot of waiting. Like anything else, there’s a lot of prep work in it.’ Image: Scott Carroll.

When he was finally selected to join the regiment, he was deployed in nations like Panama and the United Kingdom largely for jungle or cross-training. Then he returned to New York as a bike messenger, saving money so that finally he could make that trip to the Himalayas and study in a Buddhist monastery for six months, and later community college. But he always felt as if there were ‘some unfinished business’ waiting for him in the military.

Everman re-enlisted for selection for the Special Forces, seeing it as the logical progression from the Rangers. In a narrative that could only be chalked up to fate, the first day of his language skills phase, one of the last routines in Special Forces training, was on September 11, 2001. That Tuesday morning, he and dozens of other trainees stood around in the student lobby, their eyes wide and staring at the television screen, in horror the planes struck the Twin Towers.

Almost a year later, Everman was getting dropped off at a military base in Kuwait to prepare for the month-long invasion of Iraq. By April 2003, he and his fellow troops had crossed the 10-foot high dirt berm separating Kuwait from Iraq. It was during this period Everman saw for the first and possibly only time outside of training camp that war imitated art — or at least Hollywood.

‘We were being engaged from the ditches on both side of the road, the overpasses, helicopters blowing up tanks, tanks blowing up tanks.’

Jason Everman

In broad daylight, a few days after invading Iraq, he and his fellow squad members were driving north on a highway. Everman, positioned up in a gun turret of a Humvee, suddenly saw flames, explosions and gunfire surround him.

‘It sounds like a cliché, but it really was like “Wow this is like A Bridge Too Far,” something from a classic war movie,’ he says. ‘We were being engaged from the ditches on both sides of the road, the overpasses, helicopters blowing up tanks, tanks blowing up tanks.’

Today, he speaks of gunfights and warfare in almost a legal or ethical manner, one that reduces combat to an agreement of violence and human nature. When Everman speaks to me about war, he does so in the dry, rote manner that seems to echo his grandfather in the 1930s and 1940s. It involves ‘a lot of waiting,’ he says. ‘Like anything else, there’s a lot of prep work in it.’

During his graduate studies at Norwich University, he researched military history following his service in the Rangers and Special Forces largely because ‘the human story is a story built on conflict’.

Competition for resources is a problem for all organisms and conflict between groups of people, tribes and nations stem from this basic problem. Looking back on his time in the military, then, he still feels that his time serving in the military was hands-on experience ‘for studying the human condition because it’s humanity stripped to its fucking bare essence.’

‘When you think about it, combat’s a weird thing to engage in,’ he says. ‘I’m not a violent guy but I think I’m fairly decent at conducting myself as a special operation soldier. I think part of the ease of doing that is that it is essentially human.’

* * *

When Everman was a teenager, he read the autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini, an Italian Renaissance man who claimed that a well-rounded individual is one who develops himself into artist, warrior, and philosopher. Cellini practiced what he preached, studying and working as sculptor, soldier, musician and poet, among a handful of other professions and crafts.

Everman has structured his entire life around this ideology, as he believes that pursuing this trifecta of knowledge would guarantee an interesting life narrative. Having checked off the artist during his years in the grunge music scene, and later developing his warrior self by surviving training and deployment for the rangers and special forces, all that’s left is the philosopher. For Everman, that falls under the umbrella category of ‘studying the human condition’. He also calls this period ‘entering my fat biker phase’.

‘It’s things like, what else are you gonna do with this time you got on this earth, not to sound pretentious,’ he says. ‘Just working and existing, it doesn’t seem that gratifying.’

Channelling The Life Aquatic’s Steve Zissou at 50th birthday celebrations, 2017. Image: Terrence J. Allison.

Lately, his focus has turned towards food, cultivating knowledges through classes at the Hama Hama Oyster Saloon and his recurring chats with the staff over wine. Every month, in the secluded beach of the Puget Sound, Everman joins a handful of locals in tending the flames of an open fire that lick purple octopus tentacles and bacon-wrapped leeks.

Everman chuckles at his cookery being anything serious, laughing it off as ‘dilettantism’. But his raw talent is being noticed by professionals like Mitchell, his associate at the Hama Hama Oyster Saloon, and Francis Mallmann, the Patagonian chef who cooks everything from peaches and figs to butterflied chicken over an open-fire pit. Everman, who fell in love with Buenos Aires during an existential-crisis-induced trip a few years ago, has been courting Mallmann, elevator pitching the chef while he was dining at his Buenos Aires restaurant. They’re in communication now.

‘Initially it’s the food, I like that essential way of cooking he has,’ Everman says. ‘But as a man he’s a philosopher. So it was like “Oh, philosophy and food, those are both in my wheelhouse.”’

In the long-run, the goal is to open up a restaurant or maybe a bar with small plates, shaking things up daily. But walking through Chelsea, Everman further elaborates on his next, and final, great adventure. A few years ago, after reading the memoir Dove by Robin Lee Graham, who sailed around the world as a teenager, Everman bought a boat. He, too, will sail around the world.

‘It’s the classic man versus nature conflict,’ Everman says. He adds that while technology has helped with navigation, sailing ‘is almost the last experience you can have that hasn’t changed that much. You can easily get lost out sea or whatever. You’re out there with the elements.’

For the past year, he’s been training with the boatman James Fisher, hanging out on their vessels and sailing a few hours distance within the Puget Sound. Having grasped the basics, training for Everman now is mostly about being comfortable hanging out on the boat surrounded by nothing but blue water for hours. This sounds less esoteric when Everman brings up the fact that his father’s side of the family has been filled with shipbuilders and fishermen stretching back at least to Hamburg in the 18th century. Maybe the decision was some subconscious impulse to honour his family’s history. Or perhaps it was as simple as visiting remote places eventually, experiencing ‘another catalyst for growth.’

‘My intent is to keep engaged with the world, with life, with whatever I’m doing, with the people in my life,’ he says. ‘I dunno, the whole getting old thing is an adventure in itself.’