‘When I jump off I’m so in the zone, I don’t hear the crowds or the shouting or whistling.’ Blake Aldridge is in his kitchen, trying to recreate for me the sensation of jumping off a cliff. We sit at the table drinking strong tea from mugs, but in our minds we’re both plunging through the air. ‘All I hear is the whistling of the wind going past my ears,’ he continues. ‘It becomes louder and louder and louder and louder. And then suddenly it stops, just as you are about to hit the water.’

‘You feel like superman. No matter what insecurities you have it makes you fulfilled for that short space of time.’

His eyes glint. He’s a born talker this man, his words vivid with the energy of someone who’s at his happiest living in the present tense. ‘The noise stops because you are focusing on the impact,’ he says. ‘You’re going at 90/95km an hour and you probably only go five metres deep. That’s after jumping from 27/28m. The shockwave goes all the way through your body. It’s like a car crash every time you hit the water.’

There’s lightning in the eyes now. The words keep rushing, ‘…every time it’s a leap of faith. You’re battling the whole time with negatives – everything in your mind, your body, your muscles. Thoughts constantly going through my head – am I going to come out in the right place, am I going to do the right amount of somersaults, am I going to take off and forget what I’m doing in the air, and smash myself on the water and really hurt myself? Every negative thought – is the platform going to break, is it going to move when I jump, is the wind going to affect me on the way down. Is the rain going to get in my eyes when I’m spinning and twisting? Ultimately there’s no way you can possibly know if it’s going to be all right until you’ve done it. But when you do, and you get it right, there’s no feeling like it.’

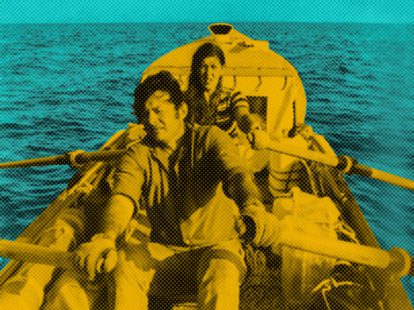

Blake Aldridge shot by David Ryle at Adrenalin Quarry, Cornwall, 18 August 2018.

He nods as if he’s just proved something. ‘You feel like superman. No matter what insecurities you have it makes you fulfilled for that short space of time and you want to go up there and do it all again. Everything happens in three and a half seconds – your senses are adapting and making decisions, hundreds and hundreds of decisions on the way down to control what you’re doing. You’ve got through that internal fight, and you feel you can overcome anything.’

‘Fight’ is a word that comes up a lot in our conversation. The cliff diving champion and former Olympic finalist started diving aged five, and at the age of 17 became the first ever British person to be made Junior World Diving Champion. Yet the route to success has contained as many flips and twists as any of his leaps off a cliff, and he freely admits that he’s felt he’s had something to prove ever since he was a child.

The long climb: ‘I don’t hear the crowds or the shouting or whistling.’

‘I didn’t find out till I was 21-years-old that I was really dyslexic. I went through the entire school system being fantastic at sport but useless academically. I was always put into the lowest classes, and I was told you have to come to these early morning classes to get extra teaching with other kids that are also struggling. Everyone would turn up to school and they would know that you’re in the extra early morning class because you’re thick, and you would get bullied. Then that would turn into me fighting someone who was taking the mickey. I was constantly fighting. But all I was doing was fighting for myself against these people who didn’t understand what I was going through. So much frustration built up inside me.’

There’s no bitterness, no edge to what he’s saying. No Rottweiler aggression, more the determination of a terrier – you can see if anything’s threatening to stop him, he’ll keep working, keep talking, keep digging through whatever obstacle presents itself till he sees the light again. Sometimes he talks too much, too frankly – as even he admits – not least when he publicly criticised former diving partner Tom Daley when they came a disappointing eighth in the 10m synchronised dive at the 2008 Beijing Olympics.

The backlash was strong, and Aldridge went through a jagged patch personally in which he was accused of shoplifting (he has claimed wrongly) and was forced to withdraw from the British Championships after being knocked unconscious in a nightclub. In 2010 he was told he would be selected neither for the world championships nor the Commonwealth Games.

Today he and Daley are on good terms again. Referring to the rift between them as ‘a total load of nonsense,’ Aldridge declares, ‘I admire what he’s achieved and I give him a great pat on the back for doing what he’s doing.’ There’s a look on his face, part mischief, part ambition – clearly he can’t help himself as he continues, ‘Because now I’ve got a new adventure, and I’ve become a world champion in cliff diving. [He was European cliff diving champion in 2009, 2010 and 2011 and since 2012 has claimed both first and second place in the Red Bull Cliff Diving Series]. And I look at that and say Tom’s never going to be a cliff diver!’ He smiles. ‘So I managed to get to the very top level of my sport in diving. And I’ve also made a transition into something way more dangerous, way more challenging, and I’ve managed to get to the top of that as well.’

‘I’ve never had any nightmares about myself, just about others I’ve dived with.’

Blake Aldridge

He’s well aware that a lot of his friends get annoyed at how relentlessly competitive he is. But there’s obviously a fierce camaraderie in the world of diving, and there’s a strong sense that Aldridge is as loyal as he is spikily combative. It’s telling that when I ask him if he ever has nightmares about cliff diving, he replies that, ‘I’ve never had any nightmares about myself, just about others I’ve dived with. One vivid dream I had was with one of my best friends, Gary Hunt, who’s currently the leader of the series, seven times world champion. He’s like a brother that I never had. I dreamed that we was down the coast and we was on this massive fort, and there was a wall that we was walking along. Twenty metres down there was a pavement if you like, and then there was the sea. We was walking along this wall 20 metres up, looking at the pavement thinking we could clear that and dive into the sea. But because it wasn’t that high I was worrying about if I would reach the sea. Gary went for it, and he hit the pavement. Then I woke up.’

He shakes his head. ‘That’s the scariest and the most vivid dream. Scariest because he’s such a great friend. You travel around the world with these guys. Gary’s someone I lived with in Southampton when we were training there. We both had a great friend of ours Gavin Brown [the 22-year-old international diver] who got killed in a hit and run when we was on a night out [in 2007]. From little kids, to full-grown adults, we’ve spent a lifetime diving together. He was in the year below me at primary school. As I say, he’s like a brother.’

‘You’re going at 90/95km an hour and you probably only go five metres deep. The shockwave goes all the way through your body. It’s like a car crash every time you hit the water.’

Aldridge’s parents broke up when he was a child, ‘they split up, divorced, got back together, split up. Both were extremely supportive in my diving career, but diving also became a sanctuary from the troubles that I witnessed at home. My dad never allowed me to show my emotions. If I cried, it was, “Stop crying or I’ll give you something to cry about.” Which is tough – because there’s been a lot of times when I’ve been so emotional, and I’ve just had to fight it.’ His own relationship history is far from simple, though he seems to be conducting it with the same mixture of toughness and open-heartedness that he displays in every other area of his life. He became a father to a baby girl in June, but is no longer with her mother. He’s still determined to be a hands-on dad though – as we drive to the station, he picks up a pink teddy-bear he’s about to deliver to her. Weeks later he’s tweeting about how much he’s missing seeing his little girl while he’s competing in a diving event in Italy.

‘Everything happens in three and a half seconds – your senses are adapting and making decisions, hundreds and hundreds of decisions on the way down.’

Where are the most spectacular places he’s ever dived? ‘There’s an old volcanic island in the Azores which is beautiful, very challenging to dive,’ he replies. ‘Diving from a helicopter in front of the Harry Potter cave [the Cliffs of Moher] in Ireland. That for me was pretty memorable.’ And what next in terms of his career? ‘I’ve said we’ll try to get into the 2020 Olympics when I’ll be 39,’ he says. (Cliff diving is not an Olympic sport yet, though there’s a campaign to change that.) ‘But now they’re looking at getting it into 2024 when I’ll be 43 and I don’t really know realistically if I could hold on that long. Because I think the sport’s going to change, I think kids are going to be coming and probably showing me how it’s done.’ He shrugs – there’s no self-pity in this statement – just an acknowledgement that that’s how the world works. ‘Till that day I’ll keep plugging away. It’s a fantastic life.’