This summer, the rapper Akon announced that he wanted to build a futuristic city in Senegal with its economy based on Akoin – his new cryptocurrency. The announcement signalled an assertive step forward for Afrofuturism, a movement that has gained significant cultural currency in recent years. That is partly because of the strong links it has built with post-capitalism, using the latest technological innovations to challenge and subvert existing systems of power.

Africans wanting to overcome economic instability, insecurity, and problems with governance have found dynamic solutions in systems including blockchain, the sharing economy, virtual currencies, peer-to-peer networks, smart contracts, De-centralised Autonomous Organisations (DAOs) and Distributed Mobile Applications.

Diovadiova Chrome Karyn V by Kip Omolade

Akon described his hi-tech vision as a real-life ‘Wakanda’, the fictional country at the heart of the Black Panther story. This ambitious project would, according to the rapper, be part of a plan to ‘bring power back to the people and bring the security back into the currency system’. Despite its headline grabbing credentials, his announcement is just the latest story to demonstrate that Africa is a world leader in taking up digital currency and blockchain. Senegal had already embraced the post-capitalist trend in 2016 when it became the second African country (Tunisia was the first) to create a cryptocurrency (eCFA) based on its mainstream currency, the West African franc (CFA). The plan was for the eCFA – created in collaboration with Senegal’s Banque Regionale de Marches (BRM) and eCurrency Mint – to be used across Francophone West Africa (though it experienced teething problems when the Western African Central Bank distanced itself from the scheme).

Beyond Senegal, individuals in South Africa, Nigeria and Ghana, have joined the race to acquire cryptocurrencies and crypto assets to gain greater access to networks and financial platforms. Many welcome the way that cryptocurrency potentially reduces the power of centralised banks to interfere with African commerce and legacies related to structural adjustment policies. They also view with approval the way that it can lessen the impact of foreign aid to interfere with local development or polity that has previously led to corruption.

It’s all an indication of how far Afrofuturism has come since the term was first coined in 1994 by cultural critic Mark Dery in his essay Black to the Future. Famously it emerged as part of a discussion about why there were so few black science-fiction writers. Author Sheree Renee Thomas, editor of the Dark Matter anthologies, had been thinking about the lack of awareness of the Black Speculative tradition and the work of black creatives, and the consequent failure to see how they had developed in parallel alongside science fiction since the 19th century. She discussed this in the introduction to the first volume in 2000, called Looking for the Invisible.

‘Can a community whose past has been deliberately rubbed out, and whose energies have subsequently been consumed by the search for legible traces of its history, imagine possible futures?’

Mark Dery

Dery asked, ‘Can a community whose past has been deliberately rubbed out, and whose energies have subsequently been consumed by the search for legible traces of its history, imagine possible futures? Furthermore, isn’t the unreal estate of the future already owned by the technocrats, futurologists, streamliners, and set designers – white to a man – who have engineered our collective fantasies?’ After he coined the term, scholar Alondra Nelson and members of the Afrofuturism.net listserv examined the overlap between race, art, science and design, embracing traditions ranging from magical realism to African history as it simultaneously interrogated and reinvented the way black people were portrayed. It was a manifestation of Black Speculative thought: transdisciplinary; subversive; and essentially imaginative.

The release of the global blockbuster movie Black Panther at the start of this year has turned it into a mainstream term. More and more people have started to engage with the phenomenon which – despite not being officially named till 1994 – traces its roots to historical figures like Martin Delany, Frances Harper, Pauline Hopkins, W E B Dubois and others. Delany’s 1859-1862 serialised publication of Blake: Or the Huts of America was a robust literary response to the over-timid characterisation of black characters in Harriet Beecher-Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Delany also promoted black nationalism and campaigned to establish an independent black nation state as a response to global white supremacy. Hopkins was the most prolific black woman writer of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as well as being an advocate of black racial uplift. In 1903 she published the speculative novel Of One Blood; Or, the Hidden Self, as a response to the emerging scientific racism and imperialism of the era.

It made sense, then, that after Dery identified Afrofuturism as a phenomenon in the 1990s, the social scientist Alondra Nelson declared that, ‘it captured what we’d always known about black culture, but it gave us something to call it, to name it…It gives us a tradition and a legacy, where all the pieces sort of fit together.’ Nelson proved to be a key figure in advancing the term, after she – in collaboration with the artist Paul D Miller – set up the Afrofuturism listserv in the 1990s in the early days of the internet. Two years later, they would follow up with Afrofuturism.net. Like its predecessor, it proved a lively forum for discussion about how themes of abduction, displacement and alienation inspired technical and creative innovations in black science fiction.

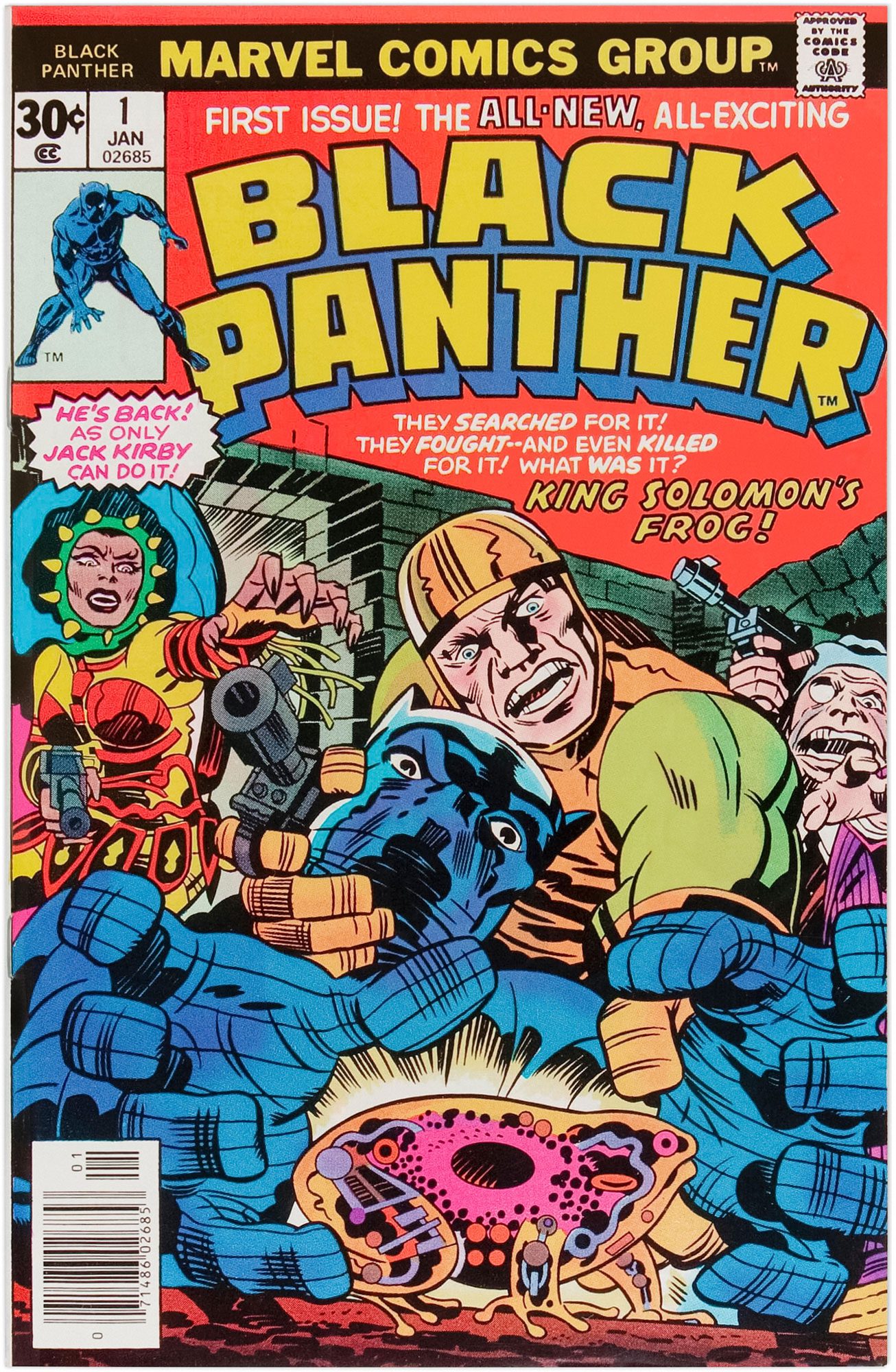

The cover of Black Panther issue #1. The character – initially developed by Jewish American comic artist Jack Kirby in the Sixties – was fundamentally ground breaking, emerging in the midst of the Cold War, the African Independence struggle, Black Power and the Black Arts movement.

As Afrofuturism’s influence grew, it started to attract established artists like John Akomfrah – a founding member of the hugely influential London-based Black Audio Collective – and the writer and filmmaker Kodwo Eshun. Akomfrah had already made his name with filmic explorations of black identity, and in 1996 directed what would prove to be a seminal video essay on Afrofuturism, The Last Angel of History. Eshun, an established cultural critic who had written extensively on cyberculture, music, and science fiction, analysed the movement with dazzling incisiveness in his 1998 work More Brilliant than the Sun: Adventures in Sonic Fiction. This was a linguistically inventive sweep through the work of Afrofuturist musicians ranging from jazz legend Sun Ra to the Detroit techno group Underground Resistance.

The American writer and editor, Sheree Renee Thomas, a member of the Afrofuturist listserv, also made an important contribution to the movement when she published Dark Matter: A Century of Speculative Fiction from the African Diaspora in 2000. These collections build a bridge between black speculative thought and contemporary Afrofuturism. One of the more historic works is Charles Chestnutt’s 1899 story within a story, The Goopherd Grapevine, narrated by a former slave. By contrast, Honoree Fanonne Jeffers’ modern Sister Lilith is a bitingly provocative reframing of Eve as Adam’s trophy wife.

Afrofuturism’s first major shift towards having a more direct impact on society came in the middle of the last decade with the emergence of social media in 2005. Figures like the graphic artist and scholar John Jennings, the digital scientist Nettrice Gaskins, the anthropologist and artist Kapwani Kiwanga, storyteller Quentin Vercetty, sonic musician Onyx Ashante, and futurist Lonnie Brooks broadened the initial Nineties framework of Afrofuturism so it took on stronger political and philosophical dimensions. It is against this backdrop that, for instance, Kenyan digital artist Osborne Macharia, who was commissioned to create work for Black Panther, has been able to talk about how he wants Afrofuturism to revolutionise people’s perception of Africa. Collectives are now emerging across Europe, South America, and Africa to represent Afrofuturism as a Pan-African transdisciplinary, transnational, trans-contextual, technocultural movement.

‘It captured what we’d always known about black culture, but it gave us something to call it, to name it.’

Alondra Nelson

This is what we now refer to as Afrofuturism 2.0. The term emerged from an exchange I had with Alondra Nelson about the inadequacy of the earlier 20th century African-American centric definition, the spring of 2013 at a conference at Emory University in Atlanta Georgia. It is a new 21st century framework, which incorporates metaphysics, aesthetics, social science, theoretical or applied science, and programmatic spaces. The original movement has cross-fertilised with important global trends in black popular culture, science, social media platforms, and politics. Currently there is an animated dialogue going on within the movement to determine its precise implication, which not the least includes what this expanded framework has for planetary Afri-humanist development.

I first became interested in the phenomenon of Afrofuturism during its early stages in the mid-1990s. This was when it was starting to harness the power of the internet in earnest, not least on a practical level – for the organization of the landmark 1995 Million Man March in Washington DC, and the 1997 Million Woman March in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The internet was also providing an increasingly wide-reaching forum for discussion, with a particularly dynamic example being the Nigerian online network Naijanet. Research done by Anna Everett elegantly points out that ironically this powerful global network would not have been possible without the emergence of Western and (Arab-centric) Slaveocracy, which fuelled the development of modern capitalism and dislocated or relocated perhaps one out of every four people of African descent into new diasporic communities. For me, contemporary Afrofuturism has become a powerful way of using speculative thought to design new alternatives for problems faced today by people of African descent around the world. All the more fascinating that the line of influence comes direct from artists like Sun Ra and the science fiction writer Samuel R Delany.

The Secret by visual artist Kaylan Michael (2018)

It’s been particularly interesting to observe Afrofuturism’s progress through the prism of the Black Panther narrative. The character – initially developed by Jewish American comic artist Jack Kirby in the Sixties – was fundamentally ground breaking, emerging in the midst of the Cold War, the African Independence struggle, Black Power and the Black Arts movement. In the summer of 1966, Kwame Ture (Stokely Carmichael) had just articulated Black Power. The same year Huey P Newton and Bobby Seal founded the Black Panther Party in Oakland, California, adopting the symbol of the Black Panther from the Lowndes County Alabama group. Kirby’s character T’challa, king of the African kingdom of Wakanda, became the first black superhero in mainstream American comics appearing in Fantastic Four issue # 56 during the summer of 1966. Incorporating elements of magic and science, the Black Panther emerged as a figure who would interact with other heroes such as the Avengers or the X-Men and was regarded as the first archetypical figure of Afrofuturism in the comic medium.

At the same time as Afrofuturism 2.0 reveals the promise and contradictions of a real-life Wakanda, it must also grapple with the fact that it has evolved with internal as well as external tensions. One particularly prominent dividing line exists between Eurocentric philosophy and Africentric, Pan African philosophy, and other Black intellectual formations, which has always underlined the Afrofuturist perspective. There is also division between contemporary Afrofuturism, which focuses on creating a new technocultural future of global Africanist-humanism as part of a new wave of liberation, and professional African futurists, who tend to embrace a set of positions around development and political economy that appear to make the future safe for neoliberalism. Another viewpoint still – the Afropolitan position – reinforces an anti-black perspective that reflects the attitudes of the most recent diaspora from Africa that sees itself as a unique urban chic, mixed heritage, transnational formation.

Beyond this, we should take into account the recent appearance of Ethnofuturism in Europe, which is correctly concerned with the rise of fascistic elements in European society. Yet the preference by Ethnofuturists for an Afropolitan Afrofuturism delinked from the geopolitical concerns and agency of people of African descent trapped in ghettos, barrios and favelas is troubling. While the other positions may have some merit, what they lack is that they are not concerned with the collective fate of a majority of people of African descent. Based upon their current stance, Ethnofuturists do not believe African peoples have the right to reconfigure narratives, or establish counter-narratives that situate themselves as agents of change or offer different pathways from western development. Moreover, there is little evidence to suggest in the last 500 years of human history their record as exploiters, new indirect rulers or representatives towards people of African descent would be anything more than largely symbolic.

People Watching/Dreams.002 by David Alabo

However, a significant development is on the horizon. Although, there have been, and are legitimate tensions between diaspora African descendants of the transatlantic slave trade and the continent, an international meeting on Afrofuturism’s second wave recently occurred in Johannesburg South Africa. The conference was a continuation of an article published by Design Indaba entitled Looking to Afrofuturism 3.0 that began the conversation of the transition of Afrofuturism 2.0, a diaspora Pan African initiative, to its adoption by the continent. The conference was co-hosted by the WiSER Institute, the Black Speculative Arts Movement and convened by author, curator, and cultural theorist Bongani Madondo and myself. The title, Telegraph to the Sky: Towards Afrofuturism 3.0, is partially taken from the title of a book by iconic poet and journalist Sandile Dikene, and explored issues around political economy, artificial intelligence and the next revolution of production, digital technology and political mobilization, African Art and hyper capitalism, and indigenous healing systems. Furthermore, almost immediately after the Johannesburg event, discussion convened with the North American African diaspora, members of the African Diaspora in Berlin, Germany with its emerging Afrofuturist 2.0 community, with European intellectuals in Rome, Italy and Bilbao, Spain, and the organization AFROFLUX in Birmingham, UK.

For the first time, these events represented Africans of the diaspora and the continent exploring issues of African futurity in the 21st century on African soil. The conference could not come at a better time as the current trajectory of the world system moves towards a post-American world order and the return of geopolitics. Moreover, participants at each of these gatherings were mindful of the other movements of futurity that are emerging in tandem with Afrofuturism such as, Sino futurism out of Asia, and autocratic influenced Arab Gulf futurism. Finally, these meetings will no doubt be influenced by global events as Africa and its diaspora navigates the currents of change over the next couple of decades as all Africans fall and rise together.

Dr. Reynaldo Anderson currently serves as an Associate Professor of Communication and Chair of the Humanities department at Harris-Stowe State University in Saint Louis Missouri. He is currently the executive director and co-founder of the Black Speculative Arts Movement (BSAM) a network of artists, intellectuals and activists. Anderson is the co-editor of Afrofuturism 2.0: The Rise of Astro-Blackness published by Lexington, co-editor of Cosmic Underground: A Grimoire of Black Speculative Discontent published by Cedar Grove Publishing, and the co-editor of Black Lives, Black Politics, Black Futures, a forthcoming special issue of TOPIA: Canadian Journal of Cultural Studies.